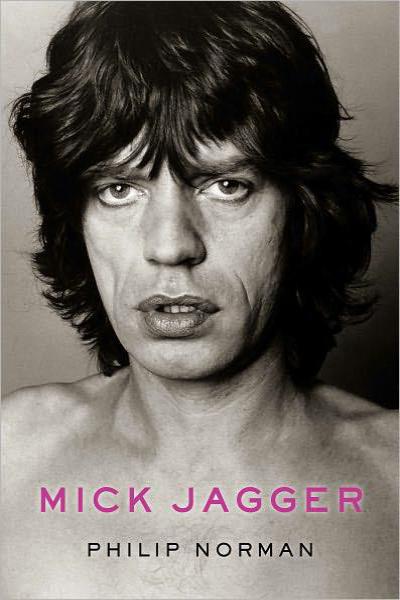

Mick Jagger

Authors: Philip Norman

TO SUE, WITH LOVE

Contents

Acknowledgments

PROLOGUE | Sympathy for the Old Devil

PART ONE: “THE BLUES IS IN HIM”

ONE | India-Rubber Boy

TWO | The Kid in the Cardigan

THREE | “Very Bright, Highly Motivated Layabouts”

FOUR | “Self-Esteem? He Didn’t Have Any”

FIVE | “ ‘What a Cheeky Little Yob,’ I Thought to Myself”

SIX | “We Spent a Lot of Time Sitting in Bed, Doing Crosswords”

SEVEN | “We Piss Anywhere, Man”

EIGHT | Secrets of the Pop Stars’ Hideaway

NINE | Elusive Butterfly

TEN | “Mick Jagger and Fred Engels on Street Fighting”

Photographs

ELEVEN | “The Baby’s Dead, My Lady Said”

TWELVE | Someday My Prince Will Come

THIRTEEN | The Balls of a Lion

FOURTEEN | “As Lethal as Last Week’s Lettuce”

FIFTEEN | Friendship with Benefits

SIXTEEN | The Glamour Twins

SEVENTEEN | “Old Wild Men, Waiting for Miracles”

EIGHTEEN | Sweet Smell of Success

NINETEEN | The Diary of a Nobody

TWENTY | Wandering Spirit

TWENTY-ONE | God Gave Me Everything

Postscript

Index

About the Author

Also by Philip Norman

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Acknowledgments

THE GREAT NINETEENTH-CENTURY painter James McNeill Whistler was once asked how long a certain canvas had taken him to complete. “All my life,” replied Whistler, meaning the years of training and dedication that had given him his abilities. Likewise, I could be said to have worked on this portrait of Mick Jagger since I first interviewed him, for a small north of England evening newspaper, in 1965. Our conversation took place on the cold back stairs of the ABC cinema, Stockton-on-Tees, where the Stones were appearing in what used to be called a pop “package show.” Mick wore a white fisherman’s knit sweater, drank Pepsi-Cola from the bottle and between answering my questions in a not very interested way, made desultory attempts to chat up a young woman somewhere behind me. That one detail, at least, would never change.

In later years, our paths crossed again from time to time, particularly when I was writing about pop music for The Times and Sunday Times of London during the 1970s. But it never occurred to me that I might be collecting material for a future book. There was, for instance, the time I found myself in Rod Stewart’s dressing room at the State theater in north London when Mick dropped by after the show. Though he was living apart from Bianca, and clearly at loose ends, that night with Stewart did not turn out as one might have expected. Rock’s two greatest Lotharios stood around a piano, chorusing sentimental Cockney songs like “My Old Dutch.”

I didn’t become a conscious Jagger watcher until 1982 when for a Sunday Times article (later the prologue to my Rolling Stones biography) I joined the band on tour in America and was granted my first formal interview with Mick since Stockton-on-Tees in 1965. This time it happened at the Orlando, Florida, Tangerine Bowl while he was doing his customary preshow warm-up on his backstage jogging track. Even before going out to perform to eighty thousand people for two hours, however, the Jagger business brain never switched off. Without pausing in his workout, he told me he’d just read my Beatles biography, Shout!, then proceeded to correct a minor point of fact relating to Allen Klein, the manager the Beatles and the Stones used to share. So much for that often repeated claim that he “can’t remember anything” about his astounding career.

It hardly needs saying that this is not an authorized biography. When I accepted the commission in 2009, I made two approaches to the now Sir Mick for cooperation, first privately through a high-level personal friend of his, then publicly through Baz Bamigboye’s show-business column in the London Daily Mail. I thought that possibly my credentials as a biographer, most recently of his old friend John Lennon, might at least arouse his curiosity. But when no response came back, I can’t say I was surprised. Sir Mick talks to writers only when he has something to sell. And then the palpitating hack—for, female or male, old or young, they all palpitate—can be relied on to churn out the same old clichés. As his one official biographer discovered, he sees no percentage in telling the truth or having it told, even where it reflects most positively on himself. The millions are all in the mythology. And the millions always come first.

So this has had to be a work of investigation and reconstruction, drawing on sources I’ve acquired during thirty years of writing about the Stones and the Beatles—who in fact constitute one single, epic story. My thrifty side was tickled to be using the same contacts book in 2009–2011 that I had for my Stones biography in 1981–1983. Inevitably, I reviewed the many hours of interview I had all those years ago with Andrew Loog Oldham, Marianne Faithfull, Keith Richards, Bianca Jagger, Anita Pallenberg, Bill Wyman, Ronnie Wood, Paul Jones, Eric Clapton, Robert Fraser, Donald Cammell, Alexis Korner, Giorgio Gomelsky, and others. But, as I did with my John Lennon biography, I promised myself never simply to recycle the group portrait into the solo one. Indeed, it will be seen that I’ve revised my view of Mick even more than I did of John.

I must record my indebtedness to Peter Trollope, a superb researcher who opened many doors—not least on the mystery of “Acid King David” Snyderman and the sinister background of the Redlands drugs bust of 1967 which put Mick briefly (but still terrifyingly) behind bars. It was through Peter, too, that I made contact with Maggie Abbott, who turned out not only to have been a friend of the elusive Acid King but also Mick’s film agent in the era when he might have become as big in movies as in rock. Maggie was endlessly helpful and patient, and the section on Mick’s wooing by Hollywood, and all those missed acting opportunities, would have been thin without her.

Special thanks go to Chrissie Messenger, formerly Shrimpton, and Cleo Sylvestre, whose recollections of the young Mick differ so greatly from the image he was given in his late teens. One great stroke of biographer’s luck came through Jacqui Graham, whom I first met when she was publicity director at Pan Macmillan publishers and I was one of her authors. Quite by chance, Jackie mentioned that in the early sixties she’d been an avid Stones fan and had kept a diary—a hilarious one, as it turned out—about following them around their early London gigs, on one occasion doorstepping Mick at home in his pajamas. My other piece of luck was being contacted by Scott Jones, a British filmmaker who has devoted years to investigating Brian Jones’s death in 1969. Brian’s mysterious drowning and the Redlands drugs raid both took place in the county of Sussex, and some local police officers were involved in both incidents. Scott generously put me in touch with two of the bobbies who collared Mick and Keith.

My gratitude to Alan Clayson, Martin Elliott, and Andy Neill for fact-checking the manuscript; to Shirley Arnold, who knows better than most that the real Mick “has no dark side”; to Tony Calder for vignettes of life with Mick and Andrew Oldham; to Maureen O’Grady for memories of Mick and Rave! magazine; to Laurence Myers for background to the Stones’ 1965 Decca deal; to Christopher Gibbs, for guidance as invaluable here as in my Stones book; to Michael Lindsay-Hogg for the backstage story of The Rolling Stones’ Rock ’n’ Roll Circus; to Sam Cutler for the new perspective on the Altamont festival; to Sandy Lieberson for the saga of Performance; to Bobby Keys for recalling “one hell of a whopper of a good time” as the Stones’ sax player; to Marshall Chess for enlightenment on the Rolling Stones Records and Cocksucker Blues era; to fellow biographer Andrew Morton for insights on Mick and Angelina Jolie; to Dick Cavett, America’s last great talk-show host, for chatting so vividly about being Mick and Bianca’s next-door neighbor in Montauk; to Michael O’Mara for his recollections of Mick’s aborted memoirs; to Gillian Wilson for the observation about Charlie Watts’s underwear.

Grateful thanks also to Keith Altham, Mick Avory, Dave Berry, Geoff Bradford, Alan Dow, John Dunbar, Alan Etherington, Matthew Evans, Richard Hattrell, Laurence Isaacson, Peter Jones, Norman Jopling, Judy Lever, Kevin Macdonald, Chris O’Dell, Linda Porter (formerly Keith), Don Rambridge, Ron Schneider, and Dick Taylor.

Finally, my continuing appreciation goes to my agents and dear friends Michael Sissons in London and Peter Matson in New York; to Dan Halpern at Ecco, New York, Carole Tonkinson at HarperCollins UK, and Tim Rostron at Random House, Canada, for their support and encouragement; to Rachel Mills and Alexandra Cliff at PFD for selling this book in other territories with such enthusiasm; to Louise Connolly for her photo research; to my daughter Jessica for the author photo—and so very much more.

—Philip Norman, London, 2012

Sympathy for the Old Devil

THE BRITISH ACADEMY of Film and Television Arts is not normally a controversial body, but in February 2009 it became the target of outraged tabloid headlines. To emcee its annual film awards—an event regarded as second only to Hollywood’s Oscars—BAFTA had chosen Jonathan Ross, the floppy-haired, foulmouthed chat-show host who was currently the most notorious figure in UK broadcasting. A few weeks previously, Ross had used a peak-time BBC radio program to leave a series of obscene messages on the answering machine of the former Fawlty Towers actor Andrew Sachs. As a result, he had been suspended from all his various BBC slots for three months while comedian Russell Brand, his fellow presenter and accomplice in the prank (who boasted on air about “shagging” Sachs’s granddaughter) had bowed to pressure and left the corporation altogether. Since the 1990s, comedy in Britain has been known as “the new rock ’n’ roll”; now here were two of its principal ornaments positively straining a gut to be as naughty as old-school rock stars.

On awards night at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, a celebrity-packed audience including Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Meryl Streep, Sir Ben Kingsley, Kevin Spacey, and Kristin Scott-Thomas received two surprises outside the actual winners list. The first was that the bad language everyone had anticipated from Jonathan Ross came instead from Mickey Rourke on receiving the Best Actor award for The Wrestler. Tangle-haired, unshaven, and barely coherent—since movie acting also lays urgent claim to being “the new rock ’n’ roll”—Rourke thanked his director for this second chance “after fucking up my career for fifteen years,” and his publicist “for telling me where to go, what to do, when to do it, what to eat, how to dress, what to fuck …”

Having quipped that Rourke would pay the same penalty he himself had for “Sachsgate” and be suspended for three months, Ross moderated his tone to one of fawning reverence. As presenter of the evening’s penultimate statuette, for Best Film, he called on “an actor and lead singer with one of the greatest rock bands in history”; somebody for whom this lofty red-and-gold-tiered auditorium “must seem like one of the smaller venues” (and who, incidentally, could once have made the Sachsgate scandal look very small beer). Almost sacrilegiously, in this temple to pure acoustic Mozart, Wagner, and Puccini, the sound system began chugging out the electric guitar intro to “Brown Sugar,” that 1971 rock anthem to drugs, slavery, and interracial cunnilingus. Yes indeed, the award giver was Sir Mick Jagger.

Jagger’s entrance was no simple hop up to the podium but a lengthy red-carpet walk from the rear of the stage, to allow television viewers to drink in the full miracle. That still-plentiful hair, cut in youthful retro sixties mode, untainted by a single spark of gray. That understated couture suit, worn in deference to the occasion but also subtly emphasizing the suppleness of the slight torso beneath and the springy, athletic step. Only the face betrayed the sixty-five-year-old, born at the height of the Second World War—the famous lips, once said to be able to “suck an egg out of a chicken’s arse,” now drawn in and bloodless; the cheeks etched by crevasses so wide and deep as to resemble terrible matching scars.

The ovation that greeted him belonged less to the Royal Opera House or the British Academy of Film and Television Arts than to some giant open-air space like Wembley or Dodger Stadium. Despite all the proliferating genres of “new” rock ’n’ roll, everyone knows there is only one genuine kind and that Mick Jagger remains its unrivaled incarnation. He responded with his disarming smile, a raucous “Allaw!” and an impromptu flash of Rolling Stone subversiveness: “You see? You thought Jonathan would do all the ‘fuck’-ing, and Mickey did it …”

The voice then changed, the way it always does to suit the occasion. For decades, Jagger has spoken in the faux-Cockney accent known as “Mockney” or “Estuary English,” whose misshapen, elongated vowels and obliterated t consonants are the badge of youthful cool in modern Britain. But here, amid the cream of English elocution, his diction of every t was bell clear, every h punctiliously aspirated as he said what an honor it was to be here tonightt, then went on to reveal “how it all came aboutt.”