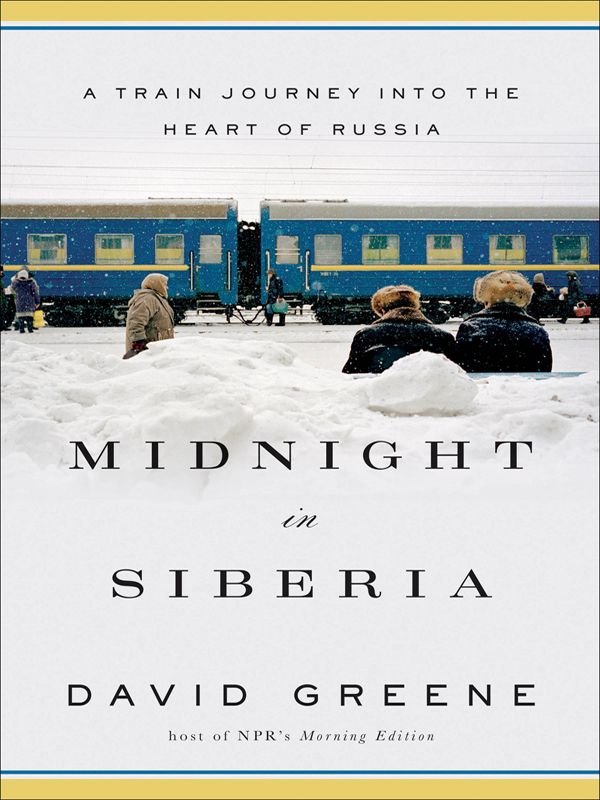

Midnight in Siberia: A Train Journey into the Heart of Russia

Read Midnight in Siberia: A Train Journey into the Heart of Russia Online

Authors: David Greene

MIDNIGHT

in

SIBERIA

A Train Journey into

the Heart of Russia

DAVID GREENE

Midnight in Siberia

is a work of nonfiction. Some of the names and certain identifying details have been changed.

T

O MY WIFE,

R

OSE

CONTENTS

The Trans-Siberian Railway is Russia’s spine, a thin line of constancy that holds this unwieldy country together. It’s more than just a map that underscores this. The railroad connects families, bringing distant relatives together more affordably than air travel. And it connects different chapters in this country’s journey—today, high-speed luxury trains carry Russia’s uber-elite and standard-class trains carry business travelers, tourists, and families, all following the same path used by Stalin to ship political prisoners to the Siberian gulags.

While the Trans-Siberian, as broadly defined, includes a number of different routes, the primary two connect Moscow to Ulan-Ude, where one route continues east to Vladivostok and the other (the Trans-Mongolian) dips south to Beijing. I decided to stick—mostly—to the all-Russia route, using the train as a vehicle and guide, seeing Russia from west to east. I did take a few detours, as you can see. I jogged over to Yaroslavl, not a stop on the main route. Same goes for Izhevsk. And I took a bus down to Chelyabinsk, hoping to pick up a southern branch of the Trans-Siberian to reconnect with the main route in Omsk. That plan fell apart when I realized I would need a Kazakh visa for a bit of that trip. It proved far more efficient to backtrack to Ekaterinburg than to take a last-minute gamble at the Kazakh consulate. From Ekaterinburg, it was a rather straightforward trip eastbound (save for a heart-thumping hovercraft ride across Lake Baikal and a late-night jump back on the train in the village of Baikalsk). Then we hugged the Chinese border, before swinging a sharp right turn and completing the home stretch into the Pacific port of Vladivostok. There we arrived, after 5,772 miles (if we’d stayed on course), more tea than vodka (not by much), more instant noodles than fresh meals (by a lot), and a whole lot of conversation.

W

ASN’T HISTORY

supposed to end in 1991?

Apocalyptic at that sounds, it was essentially the prediction of a political scientist named Francis Fukuyama who two years before that had penned an essay called “The End of History?”

As anti-Communist fervor was building around the world, Fukuyama argued that the East-West battle of ideas which fueled the Cold War was finally coming to an end. He favored nuance over finality, predicting that the world had not seen the last of totalitarian regimes and community ideology. They would ebb and flow and influence events here and there. But the trend was unmistakable: Liberal democracy, parliamentary-style governments, and market-driven economics were taking hold in more and more countries of the world. That would more or less continue. The great debate was over.

Fukuyama sure seemed prescient in December 1991, when the Soviet Union was dissolved.

The question worth asking in 2014 is whether we’ve arrived at the

end

of the End of History.

Russia, led by its enigmatic, macho leader, Vladimir Putin, blatantly ignored pleas and warnings from the West and forcibly annexed Crimea, which was (and remains, if you ask the most wishful thinkers) part of the sovereign nation of Ukraine. To foreign policy alarmists, this marked the resumption of the Cold War. To even the coolest minds, it was a seminal event likely to poison the West’s relations with Russia.

Henry Kissinger, former U.S. secretary of state and one of the world’s most influential foreign policy minds, wrote in the

Washington Post

following the Crimea annexation that it is dangerous to view Ukraine “as a showdown” over whether the sovereign nation “joins the East or the West.” Ukraine has to function, Kissinger wrote, “as a bridge between them.”

He went on to argue that the West certainly has interests in Ukraine—growing economic and cultural ties—but that so does Russia, perhaps even more. Kiev was the birthplace of the Russian Orthodox religion. Ukraine has been strategically important to Russia for centuries, especially Crimea, where Russia maintains its Black Sea naval fleet. And in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, many people speak Russian and feel a closer cultural connection to the East.

Kissinger wrote that each side has to recognize the interests of the other. He didn’t hold out much hope for that: “Putin is a serious strategist—on the premises of Russian history. Understanding U.S. values and psychology are not his strong suits. Nor has understanding Russian history and psychology been a strong point of U.S. policymakers.”

His casting of this modern conflict represents just one view. But it’s hard to argue with the reality he underscores: At worst, Ukraine could become a colossal misunderstanding that morphs into a new “showdown.” At best, Ukraine can be used as a “bridge” between competing interests and philosophies. Either way, the old fault line and the East-West battle over ideas, territory, and influence remain present today.

All of this has been building of course. The United States and its allies were furious when Russia invaded its neighbor Georgia in 2008. Likewise, Russia was furious in 2011 when it agreed under enormous pressure to abstain rather than veto on a UN vote to approve NATO military action in Libya, given assurances that NATO was going to tread delicately. NATO bombs were dropping within days.

There are reasons to think these tensions may die down. Russia and the West have shared interests, and they’ve worked together effectively at times—on space exploration and pressuring Syria to hand over its chemical weapons stockpile. Russia’s global dominance in energy may also be fading, and that could weaken Russia’s economy to a point where it must either get along with the West or face economic deprivation and collapse from within. But for now, Putin clearly believes that a stand-off with the West is in Russia’s strategic interest and that he’s strong enough to pull it off.

Just as notable as Russia’s aggressiveness abroad is Putin’s management of the home front. In recent years, he has solidified the Kremlin’s control over local and regional governments, pressured news organizations, curtailed the right to protest, and targeted minorities—most glaringly, Russians who are gay and lesbian. He has also threatened human rights organizations, especially those that receive funding from the United States and elsewhere abroad.

Most stunning? By all accounts—and admittedly, polling in Russia is often unreliable—Putin is more popular than ever.

On May 1, 2014, more than one hundred thousand Russians descended on Red Square to celebrate their president and cheer his conquering of Crimea. It was arguably the most impressive display of Russian patriotism since the Soviet collapse and quite a counterpoint to the anti-Putin protests of 2011 that received plenty of attention from Western media but appear, for the moment, largely forgotten.

If we think of 2014 as a snapshot, what do we see? A Russian leader moving further away from Western democratic values. An East-West divide marked by growing mistrust. A military stand-off that has seen both NATO and Russian forces mobilizing and carrying out exercises with the aim of intimidating.

This moment may not mark the end of Fukuyama’s End of History. Perhaps this is one of those moments he predicted when the Cold War enemy would score a blow, on the ultimate path to defeat.

I’m tempted to look at this moment differently: as a reminder that culture and history matter, values and traditions endure, peoples of the world have different instincts, wishes, priorities, and dreams. It is easy to see Vladimir Putin as an authoritative leader with his own selfish motivations who has been able to squash anyone who wants to protest and dupe everyone else into letting him lead. That portrayal may hold some truth. But Putin, popular as ever, shrewd as always, also embodies a Russian soul that is unfamiliar to many in the West.

During the Cold War, Soviet citizens were nearly impossible for Americans and others in the West to understand. Authors and journalists—Hedrick Smith among them with his book

The Russians

—took us into apartments in Russia, into the lives of people, giving us a rare window into the culture of a place that seemed so cold and threatening.

Part of understanding history and events is understanding people. And I feel lucky to have had that chance, living in Russia and, more recently, taking a wild and eye-opening trip across the vast country on a train.

Inside cramped sleeping quarters on trains, in homes, apartments, and cafés, while soaking in a Russian bathhouse or chasing debris from a meteorite, I got to meet Russians, bringing with me an ear, a deep curiosity, and no agenda.

I learned about a culture and way of life different from my own and began to understand how dangerous it is to assume that one way of thinking or any one system of government can apply everywhere.

So many Russians welcomed me into their lives. I would like to introduce you to some of them in the pages ahead.

MIDNIGHT IN SIBERIA

I

STRUGGLE AWAKE,

and there she is.

Russia.

A silver-haired grandmother in a flowered nightgown. She’s framed by the morning sunlight flooding through the dusty windowpane. And she’s holding a glass of water before my crusted eyes and parched lips.

Russia is Aunt Nina.

Here she stands, fresh and awake, despite last night’s marathon conversation about politics, childhood, dogs, snow, soccer—whatever her nephew Sergei served up next—that lasted far beyond my vodka-laced endurance. Forty years younger and barely mobile, I could be jealous of her energy or humiliated by it. Above all I just need that water. I blame Russia. No, Russia didn’t ram seventeen shots of vodka down my throat. But Aunt Nina’s family is

so

warm, and

so

persuasive. That’s what Russia does to the uninitiated at night. And now she’s greeting me in the morning—not very forgivingly.

“Dobroe utro!” That’s Russian for “Good morning,” delivered in a tone that mixes sweet and stern. Her pursed lips, tight with impatient disappointment, indicate I have only five minutes to roust myself from this bed.