Might as Well Laugh About It Now (10 page)

Read Might as Well Laugh About It Now Online

Authors: Marie Osmond,Marcia Wilkie

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs

When we finally got back out to the car, my friend’s dose of B vitamins, her hormone concoction injection in the tush, and her acupressure massage seemed to have kicked in fully. She appeared to be the picture of calm mental health. I, on the other hand, was exhausted from explaining to people that I was only having a reaction to tattoo dye. I didn’t know which was worse: the look of sympathy for my assumed relapse into PPD, or the look of horror at my lapse in judgment in having my eyelids tattooed.

As I pulled back into the driveway, I looked at my swollen, oozing eyes in the rearview mirror. I was thinking: “I should have called my brother Wayne. He would have talked me out of having this done.”

Wayne always thought I looked perfect no matter what. At this point in my life, I appreciate that more than I can possibly tell him. On my sixteenth birthday, though, his opinion made me want to disown him!

The day I turned sixteen, I was at the studio to tape the

Donny and Marie

show. I was waiting anxiously in my dressing room . . . not for the show to start, but for something much more life-changing: a complete earlobe transformation. The countdown to sixteen was over and I had arranged for a doctor to come and pierce my ears before we taped the show.

The scheduled time came and went. I couldn’t understand why it wasn’t happening. Then I found the cancellation culprit. Wayne. He was the one who had called off the appointment.

He pled his case to me, confessing that he couldn’t imagine that his baby “Sissy” was ready for pierced ears. He told me, “You weren’t born with holes in your ears, so you shouldn’t be putting any in them.”

I picked up my high heel and said to him, “You weren’t born with a hole in your head, either. But, if you don’t get out of my dressing room, you’ll be sporting a permanent Nine West shoe hat.”

I was so upset I couldn’t fathom making it through the day. I called my daddy, who was at home. Somehow he was able to understand various phrases through my sobbing: “you promised,” “why did this happen?” and “canceled.” My poor dad probably thought that the show had been canceled overnight.

He listened for about five minutes and then he stopped me.

Then he said, rather firmly, “Marie, you have to be a professional. People are counting on you right now to go out and do a show. There’s a studio audience waiting, so dry your eyes.”

I couldn’t believe it! Didn’t he understand how long I had waited for this day? Didn’t I have every right to be upset? It was my birthday!

“Marie. Pull yourself together now. I’ll be there in a little while,” he told me.

I finally stopped sobbing and said, “Okay, Daddy.”

I hung up the phone, dejected and a little angry. Then I looked at myself in the dressing room mirror. My face was splotchy from crying and my expression was that of a little child who didn’t get her way. Even at sixteen, I was embarrassed for myself and my ridiculous hissy fit.

My father had not been heartless. He was only trying to teach me about priorities. My rite of passage into being a young woman wasn’t prevented by my brother; it was only detoured. If I was mature enough to have my ears pierced, then I should be mature enough to deal with a temporary disappointment without dissolving into tears.

After the show, my father walked into my dressing room and said, “Marie, you’re a big girl, now. I want to give you something and let you know that I trust you to make your own decisions.”

My father placed in my hands a red velvet box. Inside were two perfect little diamond stud earrings. I cried again, but not from disappointment; they were tears of happiness that I had earned my father’s trust. I still have the earrings and the little box.

My eyelids and my eyeliner tattoos looked normal in about a week, but not in time for the canoe trip. I told my daughter that we could tell everyone else that I fell face-first into a wasp’s nest, even though I looked more like a fly.

Her suggestion was oversized, really dark sunglasses held in place with an elastic strap. I went with her suggestion . . . day and night! Not fun in the pitch-black when you’re trying not to fall face-first in the woods!

My first three children are all old enough now to make their own decisions about things like tattoos. As my father did before me, I’ve tried to encourage them to wait and to make consequential decisions until they feel they are ready to live with their choices. The true rite of passage is in understanding the markings and piercings of life. Every day something can happen that punches a tiny hole into our sense of self. Each experience can put a permanent etch on our hearts. So you have to be patient until you can trust yourself to make the right decision.

The Most Consistent Man

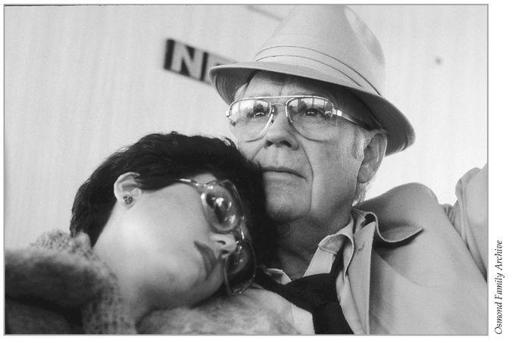

The safest place to be was always in my daddy’s arms.

My father and I share a birthday: October 13. We also shared octopus stew, sparrow spit soup, and a delicacy that was described as warm monkey brains. I hoped it was only the name of the dish . . . like Gummi Worms aren’t really worms . . . but it didn’t stop either of us from giving it a try. I was an adventurous eater, like him, which gave us some special one on one time to spend together. If that meant swallowing jellyfish tentacles, well, then pass the tartar sauce.

My dad and I were big fans of sushi decades before it became popular in the United States. Raw fish wrapped in seaweed was always an option for the two of us as we explored various Asian cities from the 1960s through the 1980s. Not one of my brothers or my mother would ever join us on our mystery menu extravaganzas. They were all too chicken to try anything, except chicken. They missed out on a lot of good memories. Ironically, my father and I never got ill, but my brothers would brush their teeth using the local water and come down with a horrible case of Montezuma’s revenge.

It wasn’t hunger that motivated my father ’s search for the favorite local restaurant; it was his endless curiosity about people, which I know has been passed on to me. He was fascinated by how people lived and worked, not so much culturally as individually. The food was secondary to hearing about how the cook learned his craft, or seeing photos of the cashier ’s new baby, or discovering that the person sitting next to us at the counter was a stand-up comic. It didn’t matter where we were in the world, my father could have a conversation with any person who made eye contact. Even with jet lag and exhaustion, my father would sit in the front seat of the cab and ask the driver about his life and goals. He knew the names of most of the crew at every venue, from the security guard to the spotlight operator.

In the last six months of his life, and three years after my mother had passed away, it became necessary for him, at age eighty-nine, to move to an assisted living residence because of a broken hip. One of my heroes, my oldest brother, Virl, had done everything possible to keep Daddy in his own home. Virl’s own children were all grown, and he chose to become the anchor for both of our parents in their final years. Their firstborn child became their last day-to-day guardian, for which the rest of my brothers and I are all so grateful.

Of the thirty or more people living at this residence, my father was one of only three men. He had nonstop visitors from our huge family, and all of the nurses and other patients loved spending time with him.

One afternoon, he tapped on my arm and motioned with his eyes around the living room area.

“All of these women that live here are flirting with me,” he whispered. “Do you think your mother would approve of that?”

“Well, you

are

quite a catch, Daddy,” I said. “But you know, you might have misled them, asking them all about their lives. You’re going to have to deal with it.”

He chuckled, his blue eyes lighting up. “Sometimes they chase me down the hall,” he whispered, “running with their walkers.”

He wasn’t kidding. More than once I would come in to find two women in their nineties bickering over who would get to sit next to George Osmond. One would be rubbing lotion into his “dry arms,” and another would be trying to shove those arms into a sweater to “keep George warm.”

My father was humble. He had spent time being a serviceman, a shoe salesman, a taxi driver, a builder, a postmaster, and he ran his own real estate business with my mother. And, of course, he managed our young careers. But no matter how my father made a living, he always “lived” for his family, and he taught us to have respect for every living thing, too.

Father bought a small ranch in Huntsville, Utah, when my brothers and I were very young. It was the place we longed to be anytime we weren’t touring or taping shows in LA. It was the inspiration for my brothers’ song “Down by the Lazy River,” although we were never very lazy in Huntsville. As kids, we didn’t know what it meant to be idle because we never saw either one of our parents just hang out.

My dad taught all of us kids to bait a hook, catch, clean, and cook fresh fish, ride a horse, round up cattle, use a bow and arrow, milk a cow, churn butter, plant a garden, harvest the garden, store fruit and vegetables, can them, and build a fire. And that was just in our first few months of life! I think he knew it would be hard for us to get big heads if we were bent over picking sweet peas from the garden and then bowing our heads to say grace at a table full of food that we had grown. We understood the beginning of all good things.

Father appreciated the “fruits of his labor” and tried never to waste anything edible. As honorable as that is, sometimes the horn of plenty made us all squawk and try to skip breakfast. When we moved to Arleta, California, in the mid-1960s, Father was thrilled that citrus trees could be grown in our yard. One white grapefruit tree seemed to have full-grown fruit hanging from its branches year-round. It must have been some kind of freaky produce-aholic tree. My dad would pick huge grapefruits almost daily and, not to waste “the bounty of the earth,” squeeze the juice so we each had a large glass waiting for us when we got up in the morning. I’m talking sixteen ounces of pure acid. Now, as an adult, it sounds refreshing, but as a little girl it was like pouring vinegar on your Frosted Flakes. (Sure, I’ll try a side of rooster feet anytime, but daily pints of white grapefruit juice were another story.) At one point, Donny, Jay, and I devised a way to have some of the problem citrus “mysteriously disappear.” We launched about fifty of the dreaded fruit over the fence and into the yard next door. They didn’t vanish for long, as our irritated neighbor, dodging our blind throws, came to the fence to complain. She scolded us for littering her lawn and we quickly collected the bowling ball-sized fruit before our parents found out.

Playtime was always as full of energy as running the ranch, but that was the way my dad wanted us to view life: as an active adventure. He would get out our tents and we would camp and paddle canoes on the lake. We’d play touch football, softball, badminton, ride bikes, and hike. He taught us to shoot BB guns, and set up target practice for our bows and arrows. In the winter we would go tobogganing, ice fishing, and take hay-rides around the ranch.