Millions Like Us (32 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

I’d been brought up in the same town but never quite got down to this level nor heard speech punctuated by so many colourful adjectives. I was under the impression that I had had a working-class upbringing but discovered that there were different categories of working-class.

In the war factories, as in the services, class distinctions were finely noted and observed. Here again, the notion that war was a great leveller is perhaps more rooted in fiction than fact. Few industrial workers in wartime had had more than an elementary school education, and literate women like Margaret Perry or genteel women like Rosemary Moonen were correspondingly conspicuous. Margaret did her best to blend in by adopting the vernacular. For Rosemary, things only improved when some new, ‘better-class’ girls – secretaries and shop-assistants – were taken on.

The welders seem not

to have been afflicted by class differences. Amy Brooke and Emily Castle loved their jobs and took pride in their welding ability. Emily was even selected to train up a number of men at the Huddersfield Foundry. Despite, or because of, such aptitude, the women welders were paid less than their male colleagues. By January 1944 the average pay for women in metalwork and engineering was, at £3 10s, exactly half that of the male rate. ‘They were jealous,’ said Dorothy Roebuck, ‘they didn’t want us to be as good as them.’

After much lobbying, women welders were permitted entry to

the Amalgamated Engineering Union in 1943, but there was little solidarity with their male counterparts, who felt threatened by their incursion on to the shop floor. In fact, there was general reluctance by the women to join unions; workplace politics were seen as a male concern. Just as men felt that tough women in overalls doing a ‘man’s job’ was a challenge to their masculinity, so women on the whole preferred to take the line of least resistance. There was a tacit acceptance on both sides that, after the war was over, when the fighter planes and tanks would no longer be required, Rosie the Riveter would return to being Rosie the housewife, cook and bottle-washer. Social structures in the 1940s had little room for working-class women to change their position in this respect.

One investigation

of attitudes among young women war workers showed that the average factory girl had little or no awareness of what she did as contributing to the war effort. According to the author of the research, this girl was half-hearted, self-centred, apathetic and unambitious for a career. ‘I’ll only be there till I marry’ was, apparently, the underlying assumption of nearly all women factory workers.

Understandable, perhaps, that home seemed preferable, given the danger, boredom and oppression of factory work. It took Arthur Askey and Gracie Fields’s famous popular song, ‘The Girl That Makes the Thing-ummy Bob (That’s Going to Win the War)’ to remind the public that her insignificant part in a larger process would ‘strike a blow for Britain’.

Making a thing

to drill a hole to hold a spring to drive a rod to turn a knob to work a thing-ummy bob might not seem heroic – ‘especially when you don’t know what it’s for’ – but the catchy lyrics helped give her a boost.

And there was another side to the story of the woman wartime worker: one that might have given credence to the worries of the moralists, who feared that such women, with money in their pockets, would take advantage of their new-found liberty.

In their off-duty

time the Yorkshire women welders let their hair down with abandon:

From Helena Marsh, March 1942

Violet and I are having a good time just now … We’ve gone to all dances and the places where one always gets merry, and have we been merry? I’ll say we have.

From Violet Champion, 10 March 1942

We went to Joan’s wedding last Saturday … And, oh boy, did we have some fun. Helena had one over the eight and went flat out.

From Amy Brooke, July 1942

I went with Harry, the Air Force boy on Sunday … We … had a couple of drinks together and then I had a cuddly Woodly, very nice.

*

From Amy Brooke, October 1942

I went to the Canteen Staff Dance on Saturday night. I had a real time and what do you think? I won the Spot Waltz Prize: a pair of Mauve Satin French Knickers and my partner won 60 Capstan Cigarettes. Just imagine the look on my face, when I opened my parcel to show him what I had won. I went crimson and did not know where to put myself. Ah ah, I bet you wish you had seen me … I had a partner all night. I did enjoy myself.

Interviewed years later, one of the group – Joan Baines – recalled that in her view war time was ‘a happy time because everybody … were all right nice … You used to have some fun.’

Amabel Williams-Ellis’s book

about women in factories also points to the wealth of opportunities they offered for social life – particularly for the ‘mobile’ women transported to live in hostels. Sometimes there were up to a thousand girls living under one roof; carnivals would be organised, and dancing partners from local RAF or army camps brought in by the bus-load.

And if ever these young women felt deprived of boyfriends, from 1942 that lack was more than compensated for by the arrival in this country of the American forces.

Yanks

For Britain, 1942 was a low point in the war, dominated from the outset by the fall of Singapore. In the first half of that year, the conflict in the Pacific continued to swing in Japan’s favour as they notched up victory after victory, and the entire eastern hemisphere seemed to be falling into Japanese hands. In North Africa, Rommel’s Afrika Korps was battling to regain mastery. Meanwhile, the German army was

pushing through Russia on its way to Stalingrad. But although the Russian campaign had caused the blitzing of British cities to abate, naval losses in the Atlantic remained severe. In Britain, the cry redoubled for a ‘Second Front Now’; American leaders were pressing to invade German-occupied Europe, and in August 1942 Churchill agreed to mount the tragic Dieppe Raid, which resulted in 3,367 casualties.

But this deeply disheartening period coincided with events at home that were more calculated to raise morale and revive jaded spirits, particularly for women:

One day … a gang of us

heard a brass band playing ‘Over There’. Yes, the Yanks had come … They soon took over. They had bigger lorries, bigger tanks, better uniforms, bigger mouths, and, rumour had it, bigger … !

Between then and D-day, a tidal wave of Americans, 2 million strong, flowed through this country, some en route to far-flung battlefields, others to stay. From Piccadilly Circus to Sutton Coldfield, from Cotswold villages to city centres, you couldn’t avoid them: the GIs (so-called after the words ‘Government Issue’, which appeared on their equipment) were everywhere. And after three years of bombs and blackout, the Yanks’ noisy, big-hearted, ‘anything goes’ sex appeal was joyfully welcomed by many British women. But the arrival of thousands of homesick 18–30-year-old men (‘overpaid, over-sexed and over here’) also sent alarm bells ringing. The seduction techniques of the GIs were so proficient that

a joke started

to do the rounds: ‘Heard about the new utility knickers? One Yank – and they’re off.’

There was fear that the US bases would become hotbeds of vice, attracting swarms of ‘good-time girls’. Hastily, the WVS and the churches set up over 200 ‘Welcome Clubs’ to entertain the American troops in a more seemly manner. Hostesses were hand-picked, and dozens of young men from Idaho and Alabama found themselves invited out to genteel Sunday afternoon tea-parties – though sometimes they had to bring their own food, as the English rations just wouldn’t stretch. The GIs were grateful; they were thousands of miles from home, missing their Mom’s pumpkin pie, yearning for warm human contact in a chilly, grey island. That loneliness was matched only by the British women’s thirst for the transatlantic glamour and luxury lifestyle they

imported.

When the GIs from Steeple Morden

8th Air Force base returned the compliment and invited a contingent of locals to a Red-Cross-organised dance, the girls started out overwhelmed and baffled: what

was

this ‘Jitterbug’, ‘with its collections of strange steps and athletic contortions’? But it was the Americans’ epicurean largesse that left them gasping:

It was the food – Food with a capital F. That was the crowning glory of that first Red Cross dance.

Spread in front of them, on groaning tables, was potato salad, macaroni salad, cold meat, rolls, butter, pickles, chocolate cake … After three years of spam, potatoes and cabbage, the girls fell upon it and ate till they could eat no more.

And now, as it dawned on the affluent Americans how pinched and deprived life in Britain had become, they became ever more bounteous. Gifts flowed: chewing gum, cigarettes, flowers, cookies, candy and above all – dearer than gold itself – nylon stockings. With their menfolk on the other side of the world, exhausted with coping and fed up with shortages, British women were only too ready to be wooed with Hershey bars and Lucky Strikes. A girl with a generous GI boyfriend could really feel like a girl again.

As Madeleine Henrey wrote:

They brought into our anxious lives a sudden exhilaration, the exciting feeling that we were still young and attractive and that it was tremendous fun for a young woman to be courted, however harmlessly, by quantities of generous, eager, film-star-ish young men … They introduced new topics of conversation, an awareness that life was not after all only tears and suffering. I felt myself, in common with the entire feminine population, vibrating to a new current in the spring air.

Our relationship with America has always been one of deep ambivalence: envy of its glamour and wealth, coupled with contempt for its perceived naivety; a fascination with its pioneering spirit, alongside mistrust of what may seem to us to be vulgarity and Philistinism. The new world feels patronised by the old, while the old feels left behind by the frenetic modernity of the new. The magnetism of Clark Gable’s Rhett Butler was potent –

Gone with the Wind

ran for four years from 1940 to 1944 – yet the improbably named American divorcée Wallis Simpson, key player in the 1936 Abdication crisis, confirmed her country’s slightly degraded image. Inevitably, all this and more entered the

sexual equation when the American army landed on these shores. In

Love, Sex and War 1939

–

1945

, the author John Costello details many of the infractions and incongruities that resulted from this sudden sexual and cultural free-for-all. His book describes the willingness of British girls to service the soldiers’ needs in return for sweets and nylons; the tricky misunderstandings that arose from the GIs’ slangy advances (was ‘Hiya baby!’ impudent over-familiarity or a friendly conversational gambit?); the random and frequent molestation and harassment of servicewomen by American soldiers; outbreaks of domestic crime and rape; infidelity; racism.

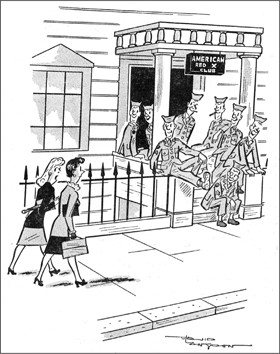

‘Don’t forget, Beryl – the response is “Hiya, fellers!” and a sort of nonchalant wave of the hand.’ GIs and the communication problem, as depicted in

Punch

, 1944.

For along with tinned peaches and chocolate, the American army imported its colour bar. English women didn’t understand the rules.

When African American

soldiers arrived in the small Glamorganshire town of Porthcawl, the local girls were only too happy to go dancing with them. Soon after, the whites arrived. Reacting with absolute horror, they immediately instituted total segregation. Seventeen-year-old Mona Janise was dismayed: ‘Talk about sin in the Garden of

Eden, we thought we had done something wrong but didn’t know what.’ Around the same time

Frances Partridge wrote

in her war diary about a public relations exercise set up by American officers for the benefit of local English ladies, ‘about how to treat the blacks’ – all of whom carried knives, apparently, and would most certainly attempt to rape their daughters. The ladies were advised never to invite them into their houses, ‘and above all never to treat them as human beings, because they were not’. Costello, however, suggests that – if British women had anything to fear – it was the predatory American soldier who, irrespective of his colour, refused to take ‘no’ for an answer.

On balance, the culture clash worked in favour of the resident women.

Dolly Scannell, a married

woman with a small child whose husband had been called up to the army, was grateful to be employed as secretary to a major at an American hospital base in Essex. Dolly, a fun-loving East Ender evacuee, was living near by with her sister Marjorie; her in-laws had also moved out of London, and her daughter Susan was in nursery school – leaving thirty-year-old Dolly to enjoy the freedom, general hilarity and perks of her new job. The GIs teased her and adored her; she was voted the girl ‘with the most terrific gams’ on camp, but turned down her prize: a weekend in Colchester with the GI of her choice. Once word got out about her ‘gams’ she had no peace – the soldiers found any excuse they could to come to her office and inspect her from the hemline down. ‘I was secretly a little bit pleased and took to wearing nylons to enhance my prancing legs.’ The stockings were, of course, one of the bonuses.