Millions Like Us (48 page)

Authors: Virginia Nicholson

Bombs, and the immensely real threat to the lives of loved ones abroad, gave an urgency to measures which women at home could perceive as making a real difference. Contemplating the bottled raspberries on their larder shelves, or wearing their refashioned coats made from army blankets, Nella and all those other women gained a sense of value, a satisfying awareness that their contribution had tangible meaning. And, somewhere inside themselves, they knew that the Spitfire pilots and tank crews had much to thank them for.

Back-room Girls

Scaling down on consumption is not a heroic or courageous activity. Heroism was for men. The majority of home-front women in the Second World War gratefully fell back on the more prosaic virtues of frugality and good housewifery. As we have seen, woman’s function as auxiliary, provider of tea-and-sympathy and generalised faithful sidekick extended across the fields, the factories and the forces. For every fighter pilot, paratrooper, submariner or commando, there were legions of women drivers, technicians, cooks, censors, plotters, administrators, wireless operators, coders, interpreters, clerks, PAs, typists, telephonists and secretaries.

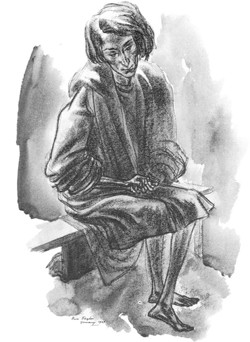

One of them was Margaret Herbertson.

Fifty years after the war was over, Margaret decided to respond to a wartime friend who suggested she write a record of their work as ‘back-room girls’ in the FANYs. Both of them had been struck that, while much had been written about their glamorous fellow FANYs who had been parachuted behind enemy lines into occupied France, enduring, in some cases, capture, imprisonment and

death in concentration camps, nothing had been said about the auxiliaries who worked behind the scenes. And yet the Special Operations Executive (SOE) was hugely dependent on their work giving aid to resistance movements and launching missions into occupied territory. As educated women from privileged backgrounds, Margaret and her friend had joined the FANYs because of its reputation as an elite volunteer service. Though nominally under the umbrella of the ATS, the FANYs had little to do with that branch of the forces, which was perceived as largely plebeian. Instead, the FANYs’ semi-autonomy made it adaptable to a wide range of purposes. Thus during the Second World War the SOE deployed a large number of its clever, confident, hard-working young volunteers both as agents in the field and as coders, wireless operators or signal planners. Between 1942 and 1944 over a hundred FANYs – most of them bright girls under the age of twenty-two – were trained by SOE and posted to the Mediterranean.

At twenty-one Margaret Herbertson was a gifted, practical but, in her own words, ‘terribly naive’ young woman. She joined SOE as a coder in late 1943. In London, she was trained in the complexities of communicating between base stations and agents in the field, using coding systems considered unbreakable, and she was told how to use bluffs, or ‘checks’, to confuse the enemy. Once she had been briefed on the clandestine nature of her work and inoculated against yellow fever, she was sent to Cairo, and thence in June 1944 to Italy – on the very day before Rome fell to the Allies. Based near Bari, her first task was to participate in a complex signals deception, designed to persuade the enemy that Marshal Tito of Yugoslavia and his HQ were still in Bosnia, when in fact they had decamped to the Croatian island of Vis. An operator was despatched to a partisan base in Bosnia, from where a two-way signals traffic was set up. ‘[We] were required to encode quantities of bogus messages … I seem to remember that this included nursery rhymes.’ The operation worked, successfully decoying hostile aircraft to the site of the false transmissions. Meanwhile, there was the added glamour of contact with field officers in the Balkans, some of whom sent coded flirtatious messages to the Bari FANYs, or ‘dolls’; from time to time they arrived in person, with tales of their manly exploits. For Margaret, these secret activities resembled life in a thriller.

In autumn 1944 Margaret joined the staff of ‘I’ branch: the Intelligence Department. Here, her new responsibilities were to learn everything she could about the location and intentions of the German forces. In addition, she was expected to conduct thorough research – garnered via reconnaissance and agents’ reports – into the terrain occupied by the enemy: its topography, politics and indigenous dynamics. This vital information was distilled daily into a fifteen-minute ‘situation report’. Such was Margaret’s responsibility in this process that her superior proposed that she be awarded a commission. But this was turned down ‘on account of my age … The disparity of treatment accorded to women, as opposed to men, still required the shake-up it was to receive in the next generation but one,’ she wrote philosophically. Eventually, Margaret herself was required to make the daily presentation, and after this the ‘brass’ caved in, and the commission was forthcoming:

On 8 November I became an Ensign and an intelligence officer. Some wag in the HQ coined the phrase ‘The nearest thing to an intelligent FANY’. It was mildly irritating, but perhaps better than being called a ‘doll’.

The front line was moving slowly and painfully northwards up the Italian peninsula. The FANYs remained at their base at Bari, with occasional exciting forays on leave to Rome and Florence, where they (respectively) attended Mass with the Pope and bought silk underclothes. Then in March 1945 Margaret’s unit was flown in a Dakota up to Siena. ‘The impact of my first sight of this delectable place was one that has never left me … Buildings reflected a pink light which was quite unforgettable, turning everything into shades of terracotta.’ The girls strolled around the medieval centre, ‘quite stunned by the beauty around us’. Their accommodation was in a gracious eighteenth-century villa across the valley from Siena; Margaret’s annexe was named

Paradiso

. Evenings at that Tuscan villa were enchanted, with the sound of the city’s bells tolling down the valley, and fireflies darting in the lengthening shade.

On the walls of another requisitioned Palazzo, they affixed their huge campaign maps, studded with myriad coloured pins and flags to display enemy formations, Partisan units and SOE missions. The task that lay ahead was to mobilise the Partisans for a planned offensive which would drive the Germans out of Italy. Weaponry was being

dropped for use by their units, and over 200 agents were working behind enemy lines. The Intelligence traffic meant a constant flow of signals from field to base, a large portion of which was deciphered, interpreted and communicated by the SOE FANYs. Sixty-five years later, Margaret still recalls the details of her daily life in Siena:

I concocted my reports in the evening, but if anything came up in the morning, they had to be changed. So I kept my wireless beside my bed, and also some notepaper. And most days I would wake up before 6, and I’d be lying there in my indestructible stripy army pyjamas – much too small for me (all the big sizes had gone) – propped up in my camp bed, listening in to what the Germans had to say, and taking notes.

She often worked ten-hour days.

My job was to tell the people with whom I was working where the Germans were, and where they were moving to. But of course the Germans never said ‘We are moving to so-and-so …’ You had to piece it together. So if for example they said they were ‘fighting valiantly’ for a village, which was north of the village they had been ‘fighting valiantly’ for the day before, that meant they were moving north. Then we also had people on the ground reporting on the German movements, who could recognise their vehicles. And they might report that certain vehicles were moving west … and one had to judge whether it was safe to drop someone there. Anyway, it was a jigsaw puzzle …

Well then I’d get up. We had no baths (we had to go into town twice a week for a bath). Breakfast was tea and British Army bread, and fig jam. We didn’t eat off the country at all because the Italians were almost starving … And then the trucks came to take us into Siena to the Headquarters.

And then at 10 past 8 all the officers of the Headquarters would come along for a ‘sit rep’, and you had to tell them what had been happening both to our own troops, and the Germans, during the past twenty-four hours.

As an Intelligence officer during the final dramatic phase of the war in Italy, Margaret was party to some of the most fascinating intrigues of that campaign. Her field contacts included daring secret agents like Dick Mallaby and Massimo Salvadori. Mallaby was parachuted into northern Italy and captured by Fascists, but secured an interview with the acting military commander of Italy, the German General Wolff, which encouraged him to start talks with the Allies about a

German surrender. Salvadori had been dropped into occupied Milan in February 1945, where with false documents he passed himself off as a civilian, while acting as under-cover head of the SOE missions in Lombardy and liaising with Partisans and the regular forces.

After the winter attrition, pressure was building against the Axis. In bed, or travelling in the truck to the mess, Margaret was rarely without her earphones, her wireless tuned to the broadcasts from the

Oberkommando der Wehrmacht

. ‘The enemy was in retreat. It was tremendously exciting.’ On 9 April the German lines were subjected to a massive aerial and artillery bombardment. Two days later all Allied forces in Italy – including the SOE FANYs – received a special order from Field Marshal Alexander. ‘Final victory is near,’ he wrote, continuing with an exhortation ‘to play our decisive part’. The Partisan wires were humming with traffic from the north. All leave was cancelled, and the FANY operators and coders were at full stretch, straining every nerve to interpret the incoming flow of messages. International armies were converging on Bologna, the gateway to the north. With the Germans in retreat Massimo Salvadori was instrumental in the uprisings of the northern cities, and the taking of German and Fascist prisoners.

On 28 April, a FANY wireless operator at HQ received an unambiguous signal from the field:

MUSSOLINI KILLED TODAY

and on the 29th the German chiefs in Italy signed an unconditional surrender at Caserta, with a ceasefire to take effect at midday on 2 May. Exhausted and dazed, the FANYs had worked themselves out of a job: ‘there was no longer an enemy’.

Until Belsen

While Margaret Herbertson was spending her waking hours tracking the German retreat in Italy,

QA Joy Taverner

was still nursing in Eeklo in Belgium. In March 1945 the Allies crossed the Rhine; the army moved on, and life in the Belgian convent settled down somewhat.

It was in mid-April that Joy received the orders that would change

her life for ever. She and a group of her fellow nurses were told to pack their things: they were to be taken into Germany to set up a field hospital. They were given no other information, before being taken to Celles airport, loaded on to a Dakota and flown north-east over Lower Saxony. It was the first time Joy had ever been in an aeroplane: ‘a frightening experience’. They landed near Bergen and were piled on to an army truck. It was 17 April 1945, just two days after the British 11th Armoured Division’s eastward advance had brought it to the gates of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

A British reporter,

Richard Dimbleby, accompanied the troops, and famously told BBC listeners what he saw there:

In the shade of some trees lay a great collection of bodies. I walked about them trying to count, there were perhaps 150 of them flung down on each other, all naked, all so thin that their yellow skin glistened like stretched rubber on their bones. Some of the poor starved creatures whose bodies were there looked so utterly unreal and inhuman that I could have imagined that they had never lived at all. They were like polished skeletons …

It was Dimbleby’s job to give a voice to the suffering, to try to make sense out of the senseless. But talkative, Irish, plain-speaking Joy, who had arrived two days earlier, was left incoherent, speechless with horror and incapable of describing what she found until forty years later. She was just twenty years old. ‘My faith deserted me after that terrible experience and I have never regained it.’

The nurses of 29th General Hospital had a job to do and they did it. As soon as they could, they set up their tented hospital. Blankets, clothes and supplies were requisitioned from local shops. The sister collected the starving babies, put them under cover and tried to feed and revive them. Belsen was huge. Ten thousand bodies were lying there unburied, but up to thirty thousand prisoners were still alive when the camp was liberated. Bodies that showed any signs of life at all were collected on stretchers. The prisoners were starved, lice-ridden and suffering from cholera, dysentery, typhus and typhoid fever. Every day people died. The nurses put a board up outside their makeshift hospital and wrote on it the numbers of bodies to be collected and taken for burial in mass graves by German POWs. As a nurse, Joy was appalled at the Germans’ disrespectful treatment of the dead. Uncovered corpses were being thrown into the graves,

bulldozed and dismembered. At her instigation, lengths of fabric were acquired, and the dead were decently wrapped. ‘Our Padre would go along and pray over each truck load.’