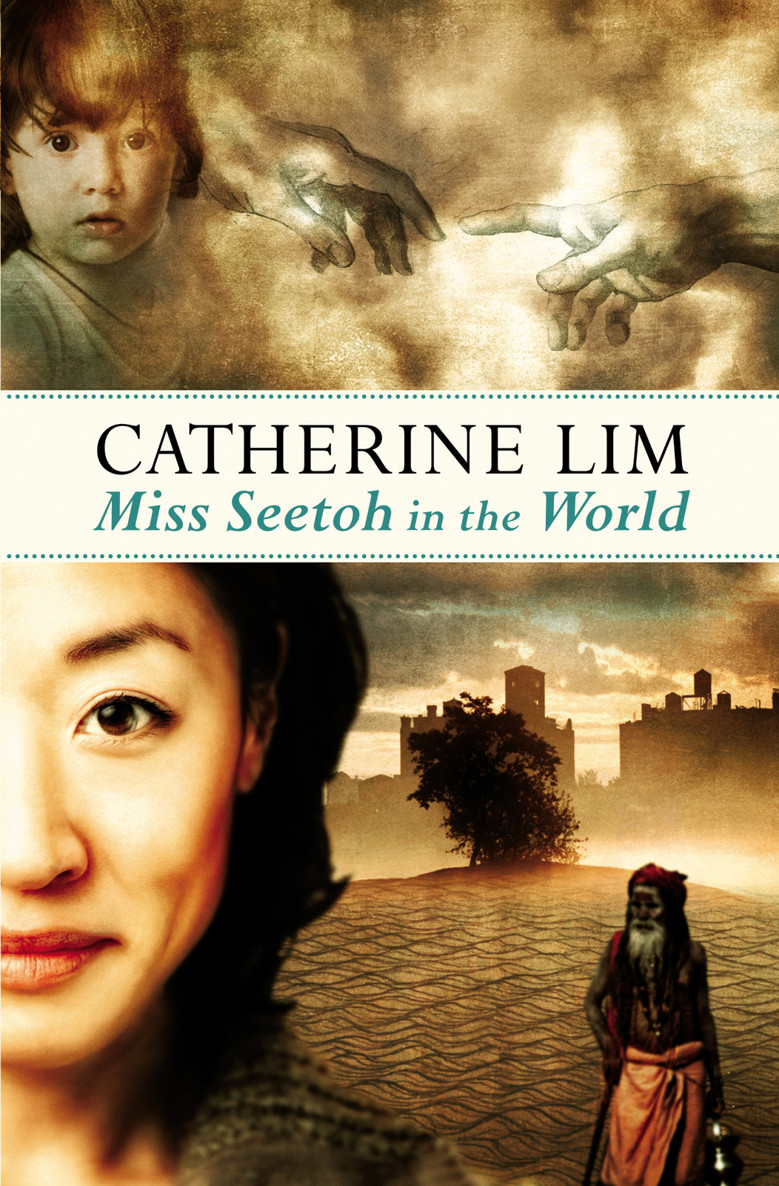

Miss Seetoh in the World

Read Miss Seetoh in the World Online

Authors: Catherine Lim

© 2011 Catherine Lim

Cover art by Opal Works Co. Limited

Published by Marshall Cavendish Editions

An imprint of Marshall Cavendish

International

1 New Industrial Road, Singapore 536196

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any

means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without

the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed

to the Publisher, Marshall Cavendish International (Asia) Private Limited, 1

New Industrial Road, Singapore 536196. Tel: (65) 6213 9300, Fax: (65) 6285

4871. E-mail: [email protected]. Website:

www.marshallcavendish.com/genref

All characters appearing in this work are

fictitious. Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely

coincidental.

The publisher makes no representation or

warranties with respect to the contents of this book, and specifically

disclaims any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any

particular purpose, and shall in no events be liable for any loss of profit or

any other commercial damage, including but not limited to special, incidental,

consequential, or other damages.

Other Marshall Cavendish Offices:

Marshall Cavendish International. PO Box

65829 London EC1P 1NY, UK • Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 99 White Plains

Road, Tarrytown NY 10591-9001, USA • Marshall Cavendish International

(Thailand) Co Ltd. 253 Asoke, 12th Flr, Sukhumvit 21 Road, Klongtoey Nua,

Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand • Marshall Cavendish (Malaysia) Sdn Bhd, Times

Subang, Lot 46, Subang Hi-Tech Industrial Park, Batu Tiga, 40000 Shah Alam,

Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia.

Marshall Cavendish is a trademark of Times

Publishing Limited

eISBN: 978-981-435-192-8

In April 1993, barely a month after her

husband’s death, Miss Maria Seetoh reverted to her maiden name. It was surely a

slight to the sanctity of the married state, endorsed both by her church in a

major sacrament, and by her society in a major economic policy by which only

married women qualified for government-subsidised housing. Moreover, it spoilt

the good name of the quietly, properly mourning widow.

Miss Seetoh made her students use the

desired name when they stood up to greet her as she entered the classroom each

morning. It had to be a carefully considered, systematic re-training of forty

young voices to make the switch from the old address, after such long

habituation, but she succeeded in a week. If a few forgot, the rest would

giggle and watch for her reaction, a full-blown ritual of pure entertainment.

She would instantly, in frowning protest, step out of the classroom, wait

outside for a few seconds, and then re-enter to face, with calm severity, the

forty boys and girls still standing at their desks. Magisterially erect, she

would wait for the little ripples of giggling whispers to subside into one

hushed enveloping silence, and then, as the last act of the elaborate ritual,

cup a listening hand to her right ear, now fully turned towards them, for the

corrected greeting. It always came in a perfectly synchronised roar of ‘GOOD

MORNING, MISS SEETOH!’, upon which the sternness vanished, and with a broad

smile and theatrical bow she acknowledged their success, and the students – oh,

how she loved them! – broke out in loud applause and laughter.

Many years later, long after Miss Seetoh had

left St Peter’s Secondary School, one of her students who became a well-known

Singapore artist held an exhibition which included a portrait of a young woman

leaning against the wall, her arms folded across her chest, her face lit up by

a smile that was the total glowing configuration of skin, mouth, teeth, eyes,

eyebrows. Miss Seetoh’s smile was ever unique. The nostalgia of memory had

perfectly reproduced her trademark turned-up shirt collar and slightly

rolled-up shirt sleeves which together with her ponytail gave an impression of

perky confidence that some of her female students tried to copy. Less imitable

was that dazzling smile, also the tiny bird-like waist discernible in the

portrait.

The principal of St Peter’s Secondary School

liked to speak of its portals of learning and tolerated their occasional

battering by the seismic eruptions from Class 4C on the third floor. The effect

on school morale, though, had to be carefully monitored and assessed, for the

walls separating the classrooms were thin, and already some students were

asking their teachers why only Miss Seetoh’s students were having all the fun.

In the staff common room one floor below where the teachers went between

lessons to mark students’ homework or sip coffee, some would ignore the ruckus,

and a few silently roll their eyes upwards at the antics of St Peter’s maverick

English language and English literature teacher. Collectively, they were dull,

dowdy and dour, beside the effervescent Miss Seetoh.

‘Come and look,’ said Mrs Neo one morning.

She was the longest serving teacher in the school, with thirty-four years’

service, just one short of earning the Golden Merit Medal from the Ministry of

Education, and she courageously defended her traditional teaching methods

against the newfangled methodologies that the younger inspectors at the

Ministry were sometimes emboldened to pass on to teachers in their training

workshops. It was said that after each workshop, she made a show of throwing

away the folders of teaching guides and notes, being completely secure, as the

rest of her colleagues were not, in her white-haired seniority and status as

the widow of one of Singapore’s most revered wartime heroes during the Japanese

Occupation. His heroic underground activities and eventual execution by the

Japanese merited some paragraphs in the history textbooks used in the schools.

Mrs Neo was just now standing at a window in

the staffroom that looked out on the school grounds. Two colleagues joined her,

and all smiled to see the strange scene in the distance. Under a large shady

tree, earnestly watched by Miss Seetoh and a group of students, two boys,

dressed in oddments of clothing meant to pass off as ancient Roman garb, were

engaged in a fearful struggle that ended with one falling to the ground with a

roar of ‘Et tu Brute!’ and the other triumphantly standing over him with a

dagger realistically smeared with red ink. A third student, in a borrowed

sarong worn toga-style, stepped out for a full oration over the corpse of the

murdered Caesar before it suddenly sprang up from the grass, in an unscripted

frenzy of crotch-pulling, screaming ‘Red ants!’, and then all was pandemonium.

The creative eccentricity of Miss Seetoh’s

teaching methods could be copied, but not of her married life which had ended

as sensationally as it had begun, creating little private stirrings of gossip

that were not allowed to disturb the smooth surface of life at St Peter’s.

Once the principal came to investigate, probably

sent by the surly discipline master who did not want to confront Miss Seetoh

himself – Miss Seetoh of the refined manners and classy way of speaking that

exposed the fumbling inadequacies of the adversary.

‘What was that noise?’ the principal asked,

and Miss Seetoh said, her eyes sparkling, ‘The noise of being happy, sir.’

Her new bright world would exclude the

judgemental and censorious, the dull and the lackluster, and would be confined

to her students, fresh-faced, eager-eyed, pure-minded, in their ridiculous

uniforms matched precisely to the pristine sky blue and white colours of the

Virgin Mary as she stood in her shrine in the school grounds.

For the few laggards who forgot the new

address for their teacher, there was a penalty: each had to pay a fine of fifty

cents, which Miss Seetoh promised to double or triple, for the amount to

snowball into a grand prize that would go to the student who had made the

greatest improvement in English grammar by the end of the year, just before the

exams.

‘There you are,’ whispered Miss Teresa Pang

to the colleague sitting beside her at the staff common room table.

She was the other English language teacher,

secretly seething from the invidious comparisons, even if implied only, with

Maria Seetoh. A school day was too long to sustain the appearance of cool,

unconcerned professionalism, which consequently broke into little sharp

comments to whoever was around to listen: ‘Breaking another school regulation

with all those money transactions going on in class! Doing it with impunity, in

her high class English.’

The famous carrots and sticks used

everywhere in the society, from the government downwards, to get people to

behave – Miss Seetoh used both with equal ferocity, the school being society’s

microcosm. She was in a witch-hunt, she told her students, to drag out and

destroy every one of their grammatical mistakes. ‘Of course,’ she said, ‘it’s

important for you to secure good grades in the O Level exams. But it’s

important for me to do something when I see you mangle and murder the language

of Shakespeare and Milton and Jane Austen!’ Miss Seetoh knew all the plays of

Shakespeare.