Modern China. A Very Short Introduction (10 page)

Read Modern China. A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: Rana Mitter

interpreted as an example of how Mao’s dominance over the CCP ended the possibilities of real debate within the leadership:

Modern C

when Peng Dehuai, the defence minister, tried to point out the hardships caused by the Leap at the 1959 Party conference at Lushan, he was abruptly dismissed from his post. Nonetheless, it should be noted that Mao was not alone in advocating the start of the Leap. Figures such as Chen Yun, the chief economic planner in the Politburo, were also highly supportive.

The Leap engendered great enthusiasm around the country, with Chinese in rural and urban areas alike taking part in mass campaigns that were not just economic but cultural and artistic as well. The breakdown of traditional family structures during the Leap helped to redefi ne women’s roles, stressing their status as workers of equal standing to men.

Yet the Great Leap Forward was a monumental failure. It can hardly be defi ned as anything else, as its methods caused a massive famine whose effects were dismissed by Mao, and caused 58

Making C

hina modern

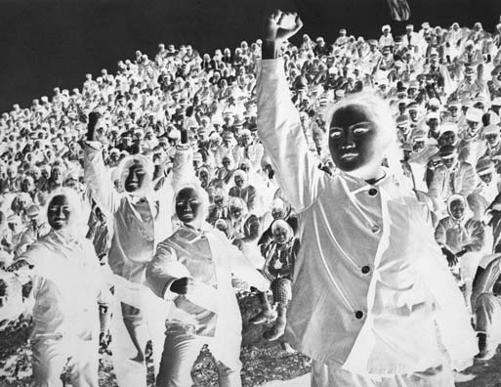

10. Chairman Mao with representatives of China’s younger generation

in his birthplace of Shaoshan during the Great Leap Forward in 1959

at least 20 million deaths. Its modernizing aims were dashed in the face of reality. Yet the return to a more pragmatic economic model in agriculture and industry when the Leap ended in 1962

did not dampen Mao’s enthusiasm for revolutionary renewal as well as ideological success. By this time, the alliance with the 59

Soviet Union had broken up in acrimony, and Soviet criticisms of Mao’s radicalism spurred him on rather than restraining his actions.

This led to the last and most bizarre of the campaigns that marked Mao’s China: the Cultural Revolution of 1966–76. In fact, the part of the Cultural Revolution that has remained in popular memory – teenage Red Guards persecuting their teachers, massive crowds of youth in Tian’anmen Square hoping for a sight of Chairman Mao – date from the early period, 1966 to 1969. But the whole decade marked the fi nal rallying call for a particular type of self-contradictory modernity which Mao hoped to instil: an industrialized state which valued peasant labour and was free of the bourgeois infl uence of the city.

Mao had become increasingly concerned that post-Leap China was slipping into ‘economism’ – a complacent satisfaction with

hina

rising standards of living that would blunt people’s revolutionary fervour. In addition, in the mid-1960s, the fi rst generation

Modern C

was coming of age that had never known any life except that under the CCP, and therefore had no personal experience of the poverty and warfare that had affl icted their parents’ generation.

For these reasons, Mao decided that a massive campaign of ideological renewal must be launched in which he would attack his own party.

Mao was still the dominant fi gure in the CCP, and used his prestige to undermine his own colleagues. In summer 1966, prominent posters in large, handwritten characters appeared at prominent sites including Peking University, demanding that fi gures such as Liu Shaoqi (president of the PRC) and Deng Xiaoping (senior Politburo member) must be condemned as

‘takers of the capitalist road’. The outside world looked on, uncomprehending, as top leaders suddenly disappeared from sight to be replaced by unknowns, such as Mao’s wife Jiang Qing 60

and her associates, later to be dubbed ‘the Gang of Four’.

Meanwhile, an all-pervasive cult of Mao’s personality took over.

A million youths at a time, known as ‘Red Guards’, would fl ock to hear Mao in Tian’anmen Square. Posters and pictures of Mao were everywhere; some 2.2 billion Mao badges had been cast by 1969. Personal devotion to Mao was now essential. For example, in June 1966, Red Guards of the high school attached to Qinghua University declared in an oath of loyalty:

We are Chairman Mao’s Red Guard, and Chairman Mao is our highest leader. … We have unlimited trust in the people! We have the deepest hatred for our enemies! In life, we struggle for the party! In death, we give ourselves up for the benefi t of the people! … With our blood and our lives, we swear to defend Chairman Mao! Chairman Mao, we have unlimited faith in you!

Making C

hina modern

11. Members of the Xiangyang Commune in Jiangsu province

perform an ‘anti-Confucius’ dance during the fi nal days of the Cultural

Revolution

61

The Cultural Revolution was not just a power grab within the leadership. The rhetoric that fl owed from the Cultural Revolution showed that not only was this a movement of great ideological conviction, but one that, despite its seeming irrationality, refl ected a particular type of modernity very strongly. ‘The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution now unfolding is a great revolution that touches people to their very souls’, began the CCP

Central Committee’s ‘Decision Concerning the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution’ (8 August 1966). The Red Guards, Chinese youth who were encouraged to rise up against their elders, embraced the call to revolution: ‘Revolutionary dialectics tells us that the newborn forces are invincible, that they inevitably grow and develop in struggle, and in the end defeat the decaying forces.

Therefore, we shall certainly sing the praises of the new, eulogize it, beat the drums to encourage it, bang the gongs to clear a way for it, and raise our hands high in welcome.’ This was the modern politics of the totalitarian state. Just as Stalin had characterized

hina

the job of Party-sponsored artists in the USSR to be ‘the engineers of human souls’, so the Cultural Revolution was meant

Modern C

to provide a retooling of Chinese society to become a renewed, self-aware citizenry fi nally free from the shackles of the past.

Like their revolutionary predecessors in the USSR and indeed in 18th-century France, the Red Guards were not ashamed to admit that their tactics were violent: a group of youths in Harbin in 1966

declared: ‘Today we will carry out Red Terror, and tomorrow we will carry out Red Terror. As long as there are things in existence which are not in accordance with Mao Zedong Thought, we must rebel and carry out Red Terror!’

With its obsessive emphasis on violence as a supposedly desirable and transformative force, the Cultural Revolution was a highly modern movement. And while Mao initiated and supported it, it also had widespread support: it was a genuinely mass political movement which left many youths feeling as if they had had the best days of their lives. It was strongly anti-intellectual and 62

xenophobic, condemning those such as doctors or teachers who were accused of being ‘expert’ rather than ‘red’, and casting suspicions on anyone who had connections with the outside world, whether the Western or the Soviet bloc. However, it also drew on Mao’s conviction that the party had become soft and too comfortable with power, obsessed with urban concerns.

Movements such as the ‘barefoot doctor’ programme took off during these years. Scorning the Ministry of Health as the

‘Ministry of Urban Gentlemen’s Health’, Mao promoted a policy by which the peasants themselves were given the opportunity to train in basic medicine and provide health care in the villages. Although inadequate in many ways, the programme brought health care to parts of China which had had few such facilities even in the years after 1949.

Making C

Yet the Cultural Revolution could not last. Worried at the increasing violence in the streets, the PLA forced the Red

hina modern

Guards back home in 1969. The policies of the Cultural Revolution remained offi cial dogma until 1976. However, from the early 1970s, profound changes began in Chinese politics.

The long-standing policy of isolation was clearly not working.

The period, however, saw a remarkable rapprochement between the United States and China, which had had no offi cial relations since 1949; the former was desperate to extricate itself from the quagmire of Vietnam, the latter terrifi ed of an attack from the now-hostile USSR and in turmoil after the sudden defection and death in an air crash of Mao’s putative successor, defence minister Lin Biao. Secretive diplomatic manoeuvres led, eventually, to the offi cial visit of US President Richard Nixon to China in 1972, which began the reopening of China to the West, although it would be more than a decade before ordinary Chinese and foreigners would be able to meet each other in any numbers within China itself. Slowly, the Cultural Revolution began to thaw, and that thaw would be accelerated by the death of its architect.

63

Gaige kaifang: reform and opening-up

Mao died in 1976. His successor was the little-known Hua Guofeng. Within two years, Hua had been outmanoeuvred by the greatest survivor of 20th-century Chinese politics, Deng Xiaoping. Deng had joined the CCP in 1924. He had been purged twice during the Cultural Revolution, but his connections had been strong enough to keep him safe, and after Mao’s death, he was able to reach supreme leadership in the CCP with a programme startlingly different from that of the late Chairman.

Deng took as his personal slogan the expression ‘seek truth from facts’, a term Mao had actually used in the 1930s, but which Deng adopted to indicate that he felt that truth and facts had been largely lacking from the political scene during the Cultural Revolution.

In particular, Deng recognized that the Cultural Revolution’s

hina

profound anti-intellectualism and xenophobia were proving economically damaging to China. Deng took up a policy slogan

Modern C

originally invented by Mao’s pragmatic prime minister and second-in-command, Zhou Enlai: the ‘Four Modernizations’.

This had been effectively an admission by moderates in the CCP

leadership that the Cultural Revolution had led China away from the path of genuine modernization. Now, the party’s task would be to set China on the right path in four areas: agriculture, industry, science and technology, and national defence.

To do so, many of the assumptions of the Mao era were abandoned. The fi rst, highly symbolic, move of the ‘reform era’

(as the period since 1978 is known) was the breaking down, over time, of the agricultural collective farms that had been instituted under Mao. Farmers, in particular, were able to sell an ever-larger proportion of their crops on the free market, and it was stated explicitly that cash crops and small private plots of land were an essential part of the economy and should not be interfered with.

Urban and rural areas were also encouraged to set up small local 64

or household enterprises, with nearly 12 million such enterprises registered by 1985.

Economic equality was no longer the goal of government. ‘To get rich is glorious’, Deng declared, adding, ‘It doesn’t matter if some areas get rich fi rst.’ As part of this encouragement of entrepreneurship, Deng designated four areas on China’s coast as Special Economic Zones, which would be particularly attractive to foreign investors, thereby ending the preference for self-suffi ciency that had marked the economy under Mao (see also Chapter 5).

Yet the doors were opened only a certain way. In December 1978, a young man named Wei Jingsheng used the new openness to demand ‘the Fifth Modernization’ – true democracy in China.

Making C

He was quickly arrested and stayed in prison almost constantly until 1997, when he was exiled to the US. Nonetheless, the 1980s

hina modern

were marked by a remarkable openness, greater than under Mao. In politics, the drive for renewal became linked with a powerful desire to reopen China to the outside world. In 1978, full diplomatic relations were fi nally established between China and the US, and from the early 1980s, foreign tourists and students began to visit China in large numbers, just as a new generation of Chinese began to study and do business abroad.

Deng Xiaoping was indubitably the senior fi gure in the party, and he made it clear that he favoured economic reform at the fastest possible speed. In the 1980s, the USSR was still intact, but the West regarded that country as a stagnant and hostile giant, at least until the arrival of Mikhail Gorbachev to the leadership in 1985. In contrast, China seemed to be the communist giant that the West loved to love. Keen to grow the economy, friendly towards the US, Deng Xiaoping even visited Texas and wore a Stetson at a rodeo. At home, cowboys of a different sort also found their moment as the economy grew by leaps and bounds.