Mona Kerby & Eileen McKeating (2 page)

Read Mona Kerby & Eileen McKeating Online

Authors: Amelia Earhart: Courage in the Sky

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women, #Juvenile Literature, #Juvenile Nonfiction, #Aeronautics; Astronautics & Space Science, #Earhart; Amelia - Juvenile Literature, #Women - Biography, #Science & Nature, #Adventurers & Explorers, #United States, #Air Pilots, #Air Pilots - United States - Biography - Juvenile Literature, #Historical, #Transportation, #Aviation, #Technology, #Earhart; Amelia

These times were happy. Amelia and Muriel spent hours reading the books and magazines in their grandfather's library. They also played with their cousins, Lucy and Katherine Challis, nicknamed Toot and Katch. The girls invented their own vocabulary. A house was called a “shouse.” Grocery boys were called “garshee boys.” Grasshoppers were called “hannibals.”

On hot summer evenings, the four cousins gathered the old skins of grasshoppers. Amelia led the way, as they slowly walked to the back of their grandparents' house. Here they placed the grasshoppers' skins on a tree stump.

Kneeling, they tapped their heads on the trunk. “Kow-tou-kow-tou to the Great Ken How,” they chanted.

Amelia struck a match to the dried grasshopper skins. While the skins burned, the girls marched around the tree stump singing, “Grumpa, grumpa, dance, dance, dance.” At the very end, they shouted at the top of their lungs, “Hannibal! Hannibal! Sizz-boom-bah!”

On Christmas eve in 1906, the year Amelia was nine, her parents arrived loaded with gifts. Two presents were exactly what Amelia wantedâa boy's sled and a gun. Of course, Judge Otis didn't approve of such things for little girls. Perhaps this was one reason that Mr. Earhart gave them to Amelia.

With the new sled, Amelia didn't sit straight as girls were supposed to do. She did “belly flops” like the boys did. Once, as she was speeding down a hill, she saw a cart and a horse on the road below. Amelia shouted, but the driver didn't hear. She couldn't stop and she couldn't turn. There was only one thing to do. Amelia slid between the horse's legs.

Amelia wanted the .22 rifle to shoot the rats in the barn. One evening, she shot a rat but it didn't die. Amelia waited nearly an hour before she saw the rat again. This time she shot and killed it. She was late for dinner, breaking one of Grandmother's rules. Amelia accepted her punishmentâthe gun was taken away.

This was probably a good idea. The barn was shot full of holes. The man who worked for Amelia's grandparents said, “Amelia gets an idea and, by gosh, she stays right with it. Dinner or no dinner, punishment or not, she wanted to get the rats.”

As a little girl and as a grown woman, Amelia was often asked why she wanted to do something. She always replied simply and stubbornly, “Because I want to.”

For her tenth birthday in 1907, Amelia saw her first airplane at the Iowa State Fair in Des Moines. She thought it was ugly with its rusty wire and wood. The plane, called a biplane, had two pairs of wings. The pilot sat in the middle and wore goggles so that the wind and bugs wouldn't get in his eyes. Another man started the plane by turning a big wooden propeller. Years later, Amelia wrote that she didn't pay much attention to the plane. She was too busy looking at her new hat made out of a peach basket.

In the summer of 1908, the Earhart girls went to live with their parents. Their new home in Des Moines was a big change for the sisters. They didn't have a maid or a cook. Instead of attending a private school, they attended the public school. By the next year, however, Mr. Earhart was promoted to a better job. The Earhart family moved to a larger house and hired servants.

As a family, they attended concerts and art shows. They belonged to a magazine club, sharing magazines with their neighbors. During the summers, they took vacations in Minnesota. They took trips in their father's private railroad car. The car had a small living room, bedroom, and kitchen. Everything seemed wonderful.

But it wasn't. Mr. Earhart began to drink too much alcohol. Several times a week he shuffled home from work. His speech was sloppy and thick. Even though he went to a hospital for treatment, he couldn't seem to stop drinking too much.

Amelia, Muriel, and Mrs. Earhart didn't let the neighbors see their sadness. They pretended everything was fine. Still, the Judge and Grandmother Otis knew that something was wrong.

In February, 1912, Grandmother Otis died. In her will, she left her money to her four children. The will stated, however, that Amy's share was to be held by the bank for twenty years or until Edwin Earhart died. Mr. Earhart was ashamed and embarrassed. He began to drink even more.

And finally, in 1913, he lost his job. Amelia was sixteen years old. She had to leave her high school and her friends. The Earhart family left for St. Paul, Minnesota, where her father found work as a clerk in a railroad office.

Since Amelia and Muriel were new, they weren't invited to many parties. They didn't have the money to join the fancy skating and social clubs. In December of that year, they looked forward to a party at their church. Back then, fathers brought their daughters to dances. Mr. Earhart promised to come home in plenty of time. Instead, he came home late. He was drunk. Muriel cried, but Amelia refuse to shed a tear. She threw out the marshmallows which they had planned to have with their hot chocolate after the dance. She tore up the Christmas decorations.

Since there wasn't money for spring clothes, Amelia took matters into her own hands. She found curtain material in the attic and made skirts for herself and for Muriel. They dyed their skirts and painted their old hats and wore them on Easter morning.

Amelia didn't complain. In fact, she managed to make Muriel laugh. If it rains, she warned, get under shelter before you leave a trail of green dye.

Things didn't get better. Mr. Earhart was offered another job. This time, they moved to Springfield, Missouri. Their family arrived in the fall of 1915 with all of their belongings. But a man who was supposed to retire had changed his mind. There was no work for Mr. Earhart after all.

Mrs. Earhart made a painful decision. She left her husband. She took the girls to Chicago and stayed with friends. Brokenhearted, Mr. Earhart lived with his sister in Kansas City. Since he couldn't get a job as a lawyer with the railroad, he opened his own law office.

In Chicago, Amelia entered Hyde Park High School. The English teacher had trouble controlling the class. Amelia didn't want to spend the entire year learning nothing. She talked the principal into letting her read in the library during English period. Although this was a way to learn, it was not a way to make friends. The words under her picture in the school yearbook read, “The girl in brown who walks alone.”

It was almost as if the students had seen into the future. Amelia Earhart would achieve great fame all by herself. But first, she received some welcome help from her family.

3

The Little Red Plane

In the summer of 1916, Amy, Amelia, and Muriel rejoined Edwin Earhart in Kansas City. He was overjoyed. Edwin wanted to help his family again. For this reason, he talked Mrs. Earhart into going to court to break Grandmother Otis's will. Mrs. Earhart's brother, who took care of her money, had lost much of it on bad business deals. The court ruled in Mrs. Earhart's favor. She used the money to send her daughters to good schools.

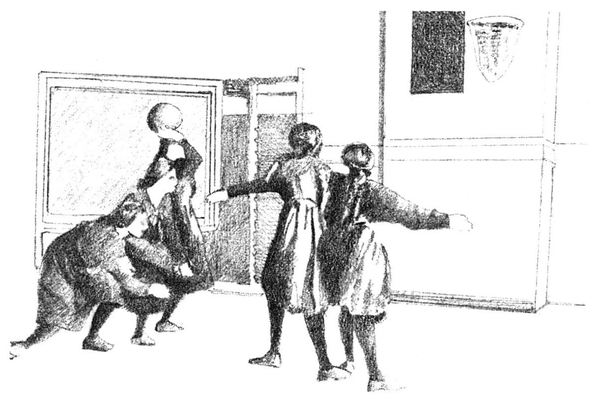

In the fall of 1916, Amelia arrived at the Ogontz School in Rydal, Pennsylvania. She was an excellent student and an outstanding athlete. She liked to play hockey, basketball, and tennis. Her letters to her mother were happy and filled with the details of her school activities.

Amelia was tall and slender, and the girls quickly nicknamed her Butterball. They liked her and Amelia liked them. Still, she was not afraid to speak her mind.

During her first year at school, Amelia belonged to a secret club. When she realized that some students had not been invited to join, she asked the members to include the other girls. They refused. Amelia went to the headmistress, who ran the school, and asked that another club be added for these girls. Instead, the headmistress did away with the secret clubs.

On another occasion, Amelia argued that the students should have the freedom to discuss and read anything they wanted. These actions set her apart from the other girls. But, as always, whenever Amelia believed in something, she was willing to “walk alone.”

For Christmas of 1917, Amelia and her mother visited Muriel in Toronto, Canada, where Muriel was at school. One day, as Amelia walked down King Street, she saw something that changed her life. She met four young men using crutches. Each of them was missing a leg.

The young men had been hurt in battle. For three years, there had been war. The Great War, as it was called then, lasted four years. (Almost 25 years later, the Great War was renamed World War I, when World War II began.) The Great War destroyed countries, governments, homes, and lives. Nearly 10 million soldiers were killed. More than 15 million people were wounded.

While at school, Amelia had knitted socks for soldiers. Until she met the soldiers in Toronto, however, she didn't fully understand the horrors of fighting.

Right then and there, Amelia made a decision. With her mother's permission, she did not return to school. Instead, she stayed in Toronto and became a nurse's aide.

She worked from seven in the morning until seven at night, with two hours off in the afternoon. At the hospital, Amelia gave medicine, scrubbed floors, prepared meals, gave back rubs, and wrote letters for soldiers.

When Amelia had spare time, she liked to ride a wild horse named Dynamite. One soldier told her that she rode Dynamite the way he flew his plane. Sometimes the ride was smooth and sometimes it was rough. Amelia stayed on the horse.

Something else caused Amelia to think about planes. One afternoon at an air show in Toronto, Amelia and a friend were watching a pilot doing stunts in the air. Perhaps to tease the girls, the pilot headed for them. Amelia's friend screamed and ran, but Amelia stood still. She heard the sound of the motor. She felt the wind on her face. She was excited. Years later, she wrote, “I believe that little red airplane said something to me as it swished by.”

When the war was over in 1918, Amelia became ill with pneumonia (say, “new-MOAN-ya”). Muriel had moved to Northampton, Massachusetts. Amelia stayed with her sister and spent nearly a year resting and recovering. She bought an old banjo and learned to read music. Like her father, Amelia played by ear. Once she heard a melody, she could then play it. She also signed up for a five-week course in car repair.

In the fall of 1919, she entered Columbia University in New York City. She wanted to be a doctor. She had always liked science and she did well in her classes. For fun, Amelia took a course in French poetry. And for excitement, she used to sit on top of the Columbia library dome. Somehow, Amelia discovered where the key to the roof was kept. Dressed in her hat and long skirt, she would crawl out onto the roof. There she sat on the sloping roof, hugging her knees and staring at the buildings below her.

By the spring of 1920, Amelia decided she really did not want to study medicine. Her parents had moved to Los Angeles, California, and they asked her to live with them. Even though her father was no longer drinking, they weren't happy. Amelia wanted to help.

Other books

Crazy Hot by Tara Janzen

Absolution by Murder by Peter Tremayne

The Chevalier (Châteaux and Shadows) by Philippa Lodge

The Siege by Alexie Aaron

Max Stops the Presses: A Gardella Vampire Chronicles Short Story by Colleen Gleason

Lethal Vintage by Nadia Gordon

Breakdown (Crash into Me) by Lance, Amanda

Lola's House (Lola Series) by Groers, Suzie

The Worker Prince by Bryan Thomas Schmidt

Royal House of Shadows Box Set: Lord of the Vampires\Lord of Rage\Lord of the Wolfyn\Lord of the Abyss by Showalter, Gena, Monroe, Jill, Andersen, Jessica, Singh, Nalini