Moneyball (Movie Tie-In Edition) (Movie Tie-In Editions) (37 page)

Read Moneyball (Movie Tie-In Edition) (Movie Tie-In Editions) Online

Authors: Michael Lewis

Tags: #Sports & Recreation, #Business Aspects, #Baseball, #Statistics, #History, #Business & Economics, #Management

“Ray was

bred

on being aggressive running the bases,” says Wash. “Until he got here he

never

got chastised for being aggressive on the base paths.”

Crack!

Ray lines a pitch off the foot of bullpen catcher Brandon Buckley, who has been pitching to him from behind a screen. As Brandon hops around and tries to figure out if he’s broken something, Ray turns and says, “The White Sox always told us an aggressive mistake is not really a mistake.”

Wash is overcome with fellow feeling. Here they have this specimen of base-running prowess

and no one gives a shit.

He says, “Ray, what you thinkin’ about when you put the ball in play?”

“Second base.”

“As long as the ball is rolling?”

“I’m runnin’.”

“You runnin’.”

“A single is a double,” says Ray.

“A double is a triple,” says Wash.

Nobody says anything for a minute. Then Wash says, “Different situation here. Somebody on this team runs and get his ass thrown out and you got all kinds of

gurus

who tell you that you just took yourself out of the inning.”

“I never seen anything like it,” says Ray.

T

WO THINGS

happened toward the end of every season, after Billy Beane’s Oakland A’s have secured a play-off spot. The first was a slightly unseemly attempt by a small handful of staff members to use the newspapers to create pressure on the GM to improve their standard of living. The most transparent of these was an interview given by manager Art Howe to the

San Jose Mercury News

, on the subject of a long-term contract for himself. “With all the years I’ve been here and with what we’ve accomplished,” he said, “I would think I deserve it. My thinking is, if I don’t get it here, I’ll get it somewhere else.” After Art’s wife confessed that she, too, was befuddled by Billy Beane’s unwillingness to secure their retirement years, Art mentioned how struck he was by how different baseball teams arrange their pecking order. “Down in Anaheim,” he said, “all they talked about is the manager. I don’t think most people even know who the general manager is down there.”

The other thing that invariably happened was an unsystematic rethink in the engine room about this quixotic course the captain has set all season long. Coaches, players, reporters: everyone at once starts to worry that the Oakland A’s don’t bunt or run. Especially run. Billy Beane’s total lack of interest in the stolen base—which has served the team so well for the previous 162 games—is regarded, in the postseason, as sheer folly. Even people who don’t run very fast start saying that “you need to make things happen” in the postseason. Take the action to your opponent. “The atavistic need to run,” Billy Beane calls it.

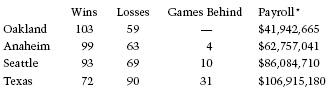

The regular season is all but forgotten, but it shouldn’t be. Any way you looked at it, it had been a miracle. In all of Major League Baseball only the New York Yankees won as many games as the Oakland A’s. All but written off when they let Jason Giambi leave for greener pastures, the A’s had won 103 games, one more than they had the year before. Maybe more astonishingly, at least for economic determinists, the teams in baseball’s best division, the American League West, finished in inverse order to their payrolls.

The more money the teams spent on players, at least in the American League West, the less able those players were to win baseball games. The same wasn’t exactly true in every other division, but there had been plenty of other astonishing endings: big-budget disasters (the Mets, the Dodgers, the Orioles) and low-budget successes (the Twins).

In spite of the Oakland A’s fantastic success, there was a subtle pressure to change the way they did business. Most of it came from the media. About the fifteenth time he heard some TV pundit say that the Oakland A’s couldn’t win because they didn’t “manufacture runs,” Billy began to worry his coaches and players might actually believe it. He printed out the 2002 offensive statistics for the Oakland A’s and the Minnesota Twins and sat down with the coaches. The Twins team batting average was 11 points higher than the A’s, and their slugging percentage was 5 points higher. And yet they had scored thirty-two fewer runs. Why? Their team on-base percentage was a shade lower, and they’d been caught stealing sixty-two times, to Oakland’s twenty, and had twice as many sacrifice bunts. That is, they’d squandered outs. “They were trying to manipulate the game instead of letting the game come to them,” said Billy. “The math works. But no matter how many times you prove it, you always have to prove it again.”

The moment the play-offs began, you could feel the world of baseball insiders rising up to swat down the possibility that the Oakland A’s front office actually might be onto something. The man who spoke for all insiders was Joe Morgan, the Hall of Fame second baseman, who was in the broadcast booth for the entire five-game series between the A’s and the Twins. At some point during each game Morgan explained to the audience the flaw in the A’s thinking—not that he had any deep understanding of what that thinking entailed. But he was absolutely certain that their strategy made no sense. When the A’s lost the first game, 7–5, it gave Morgan his opening to explain, in the first inning of the second game, why the Oakland A’s were in trouble. “You have to manufacture runs in the postseason,” he said, meaning bunt and steal and in general treat outs as something other than a scarce resource. Incredibly, he then went on to explain that “manufacturing runs” was how the New York Yankees had beaten the Anaheim Angels the night before.

I had seen that game. Down 5–4 in the eighth inning, Yankees second baseman Alfonso Soriano had gotten himself on base and stolen second. Derek Jeter then walked, and Jason Giambi singled in Soriano. Bernie Williams then hit a three-run homer. A reasonable person, examining that sequence of events, says, “Whew, thank God Soriano didn’t get caught stealing; it was, in retrospect, a stupid risk that could have killed the whole rally.” Joe Morgan looked at it and announced that Soriano stealing second, the only bit of “manufacturing” in the production line, was the

cause

. Amazingly, Morgan concluded that day’s lesson about baseball strategy by saying, “You sit and wait for a three-run homer, you’re still going to be sitting there.”

But the wonderful thing about this little lecture was what happened right under Joe Morgan’s nose, as he was giving it. Ray Durham led off the game for Oakland with a walk. He didn’t attempt to steal, as Morgan would have him do. Scott Hatteberg followed Durham and he didn’t bunt, as Morgan would have him do. He smashed a double. A few moments later, Eric Chavez hit a three-run homer. And Joe Morgan’s lecture on the need to avoid playing for the three-run homer just rolled right along, as if the play on the field had not dramatically contradicted every word that had just come out of his mouth. That day the A’s walked and swatted their way to nine runs, and a win—in which Chad Bradford, returned to form, pitched two scoreless innings. Two days later in Minnesota, before the third game, Joe Morgan made the same speech all over again.

As it turned out, the A’s did everyone in baseball a favor and lost to the Twins, in the fifth game.

*

The two games they won the scores were 9–1 and 8–3. The three games they lost the scores were 7–5, 11–2, and 5–4. These were not the low-scoring games of Ray Durham’s play-off imagination. And yet virtually all of the noisy second-guessing after their defeat followed the line of reasoning laid down by Ray Durham and Joe Morgan. One of the leading Bay Area baseball columnists, Glenn Dickey of the

San Francisco Chronicle

, explained to his readers that “The A’s don’t know how to ‘manufacture’ runs, which kills them in close games in the postseason. Manager Art Howe, who believed in ‘little ball’ before he came to the A’s, has become so accustomed to the walk/homer approach that he can’t adjust in the postseason.” In late October, Joe Morgan will summarize the Oakland A’s problems in print: “The A’s lose because they are two-dimensional. They have good pitching and try to hit home runs. They don’t use speed and don’t try to manufacture runs. They wait for the home run. They are still waiting.”

All of the commentary struck the Oakland A’s front office as just more of the same. “Base-stealing,” said Paul DePodesta, after the dust had settled. “That’s the one thing everyone points to that we do. Or don’t. So when we lose, that’s why.” He then punched some numbers into his calculator. The Oakland A’s scored 4.9 runs per game during the season. They scored 5.5 runs per game in the five-game series against the Twins. They hadn’t “manufactured” runs and yet they had scored more of them in the play-offs than they had during the regular season. “The real problem,” said Paul, “was that during the season we allowed 4.0 runs per game, and during the play-offs we allowed 5.4. The small sample size makes that insignificant, but it also punctuates the absurdity of the critiques of our offensive philosophy.” The real problem was that Tim Hudson, heretofore flawless in big games, and perfect against the Minnesota Twins, had two horrendous outings. No one could have predicted that.

The postseason partially explained why baseball was so uniquely resistant to the fruits of scientific research: to

any

purely rational idea about how to run a baseball team. It wasn’t just that the game was run by old baseball men who insisted on doing things as they had always been done. It was that the season ended in a giant crapshoot. The play-offs frustrate rational management because, unlike the long regular season, they suffer from the sample size problem. Pete Palmer, the sabermetrician and author of

The Hidden Game of Baseball

, once calculated that the average difference in baseball due to skill is about one run a game, while the average difference due to luck is about four runs a game. Over a long season the luck evens out, and the skill shines through. But in a series of three out of five, or even four out of seven, anything can happen. In a five-game series, the worst team in baseball will beat the best about 15 percent of the time; the Devil Rays have a prayer against the Yankees. Baseball science may still give a team a slight edge, but that edge is overwhelmed by chance. The baseball season is structured to mock reason.

Because science doesn’t work in the games that matter most, the people who play them are given one more excuse to revert to barbarism. The game is structured, psychologically (though not financially), as a winner-take-all affair. There isn’t much place for the notion that a team that falls short of the World Series has had a great season. At the end of what was now widely viewed as a failed season, all Paul DePodesta could say was, “I hope they continue to believe that our way doesn’t work. It buys us a few more years.”

B

ILLY BEANE

had been surprisingly calm throughout his team’s play-off debacle. Before the second game against the Twins, when I’d asked him why he seemed so detached—why he wasn’t walking around the parking lot with his white box—he said, “My shit doesn’t work in the play-offs. My job is to get us to the play-offs. What happens after that is fucking luck.” It was Paul who took a bat to the chair in the video room, late at night after the fifth game, after everyone else had gone home for good. Billy’s attitude seemed to be, all that management can produce is a team good enough to triumph in a long season. There are no secret recipes for the postseason, except maybe having three great starting pitchers, and he had that.

His objective spirit survived his team’s defeat a week. The fact that his team had lost to the clearly inferior Minnesota Twins festered. He never said it, but it was nonetheless evident that he couldn’t quite believe how little appreciation there was for what he’d done. Even his owner, who was getting multiples more for his money than any owner in baseball, complained. The public reaction to the thing ate at Billy. In these situations, when his mind was disturbed, he often went looking to make a trade. But there was no player on whom his mind naturally fixed; the only person in the organization whose riddance would make him happier was his manager, Art Howe. It wasn’t long before he had a novel idea: trade Art.

It took him about a week to do it. He called New York Mets GM Steve Phillips and told him that Art was a superb manager but his latest one-year contract called for a big raise, and Oakland couldn’t really afford to pay it. Phillips had just fired his own manager, Bobby Valentine, and was in a bit of a fix. Billy had thought he might even get a player from the Mets for Art but in the end settled on moving Art’s salary. Art signed a five-year deal for $2 million a year to manage the New York Mets. In Art’s place Billy installed Ken Macha, the A’s bench coach.

That made him feel better for a bit. Then it didn’t. He had the feeling he’d come to the end of some line. Here they had run this low-budget franchise as efficiently as a low-budget franchise could be run and no one had even noticed. No one cared if you found radically better ways to run a big league baseball team. All anyone cared about was how you fared in the postseason crapshoot. For his work he’d been paid about as well as a third-year relief pitcher, and Paul had been paid less than the major league minimum. Billy was worth, easily, more than any player; his services were more dramatically undervalued than those of any player he’d ever acquired. He could see only one way to exploit this grotesque market inefficiency: trade himself.