Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power (4 page)

Read Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power Online

Authors: Robert D. Kaplan

Tags: #Geopolitics

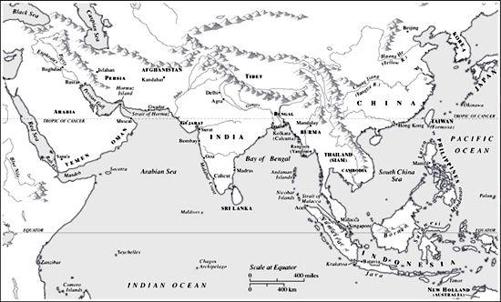

It is more productive, instead, to think of a multiplicity of regional and ideological alliances in different parts of the ocean and its littoral states. There is already evidence of it. The navies of Thailand, Singapore, and Indonesia, with the help of the U.S. Navy, have banded together to deter piracy in the Strait of Malacca. The navies of India, Japan, Australia, Singapore, and the United States—democracies all—have exercised together off India’s southwestern Malabar coast, in an implicit rebuke to China’s design on the ocean, even as the armies of India and China have conducted exercises together near the southern Chinese city of Kunming. A combined naval task force, comprised of the Americans, Canadians, French, Dutch, British, Pakistanis, and Australians, patrols permanently off the Horn of Africa in an effort to deter piracy.

The Indian Ocean strategic system has been described by Vice

Admiral John Morgan, former deputy chief of naval operations, as like the New York City taxicab system, where there is no central dispatcher—no United Nations or NATO—and maritime security is driven by market forces; coalitions will appear where shipping lanes need to be protected, just as more taxis show up in the theater district before and after performances.

No one nation dominates, even as the U.S. Navy is still quietly the reigning hegemon of the seas. As one Australian commodore told me: imagine a world of decentralized, network-centric sea basing, supplied by the United States, with different alliances for different scenarios; whereby frigates and destroyers of various nations can “plug and play” into these sea bases that often resemble oil rigs, spread out from the Horn of Africa to the Indonesian archipelago.

The U.S. military, with its sheer size and ability to deploy rapidly, will still be indispensable, even as the United States itself plays a more modest political role, and other, once-poor nations rise up and leverage one another. After all, this is a world where raw materials from Indonesia are manufactured into component parts in Vietnam and supplied with software from Singapore, financed by the United Arab Emirates: a process dependent on safe sea-lanes that are defended by the U.S. and various naval coalitions. The Indian Ocean may not have a unitary focus, like the Soviet threat to the Atlantic, or the challenge of a rising China in the Pacific, but it certainly does constitute a scale model of a global system.

And yet within this microcosm of a radically interconnected global system, ironically nationalism will still flourish. “No one in Asia wants to pool sovereignty,” writes Greg Sheridan, foreign editor of

The Australian

. “Asia’s politicians have come up through hard schools and amid hard neighbors. They appreciate hard power; the U.S. position is much stronger in Asia than anywhere else in the world.”

24

In other words, do not confuse this world with the one of the United Nations, which in any case is partly an old construct with France having a seat on the Security Council but not India. India, Japan, the United States, and Australia sent ships steaming to tsunami-afflicted zones in Indonesia and Sri Lanka in December 2004 without initial reference to the U.N.

25

Overlapping configurations of pipelines and land and sea routes will lead more to Metternichean balance-of-power politics than to Kantian post-nationalism. A non-Western world of astonishing

interdependence and yet ferociously guarded sovereignty, with militaries growing alongside economies, is being tensely woven in the Greater Indian Ocean. Writes Martin Walker, senior director of A. T. Kearney’s Global Business Policy Council:

The combination of Middle Eastern energy and finance with African raw materials and untapped food potential and Indian and Chinese goods, services, investments and markets looks to be more than just a mutually rewarding triple partnership. Wealth follows trade, and with wealth comes the means to purchase influence and power. Just as the great powers of Europe emerged first around the Mediterranean Sea until the greater trade across the Atlantic and then across the Pacific produced new and richer and more powerful states, so the prospects are strong that the Indian Ocean powers will develop influence and ambition in their turn.

26

And so this ocean is once again at the heart of the world, just as it was in antique and medieval times. To consider that history, and to explore the ocean part by part, let us begin with Oman.

*

The Persian Gulf is responsible for 57 percent of the world’s crude oil reserves.

†

In January 2004 the China Petrochemical Corporation signed a contract with Saudi Arabia for the exploration and production of natural gas in a nearly 15,000-square-mile area of the Empty Quarter, in the south. As air pollution becomes an increasingly serious problem in China because of the burning of dirty fossil fuels, China will turn to cleaner natural gas. Geoffrey Kemp, “The East Moves West,”

National Interest

, Summer 2006. In any case, China’s oil consumption is growing seven times faster than that of the U.S. Mohan Malik, “Energy Flows and Maritime Rivalries in the Indian Ocean Region” (Honolulu: Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, 2008).

OMAN IS EVERYWHERE

T

he southern shore of the Arabian Peninsula is a near wasteland of igneous colors, with humbling plains and soaring, knife-edged formations of dolomite, limestone, and shale. Broad, empty beaches go on in all their undefiled grandeur for hundreds of miles. The hand of man seems truly absent. The sea, though mesmerizing, has no features to stimulate historical memory, so the vivid turquoise water suggests little beyond a tropical latitude. But the winds tell a story. The monsoon winds throughout the Indian Ocean generally north of the equator are as predictable as clockwork, blowing northeast to southwest and north to south, then reversing themselves at regular six-month intervals in April and October, making it possible since antiquity for sailing ships to cover great distances relatively quickly, with the certainty, perhaps after a long sojourn, of returning home almost as fast.

*

Of course, it was not always that simple. Whereas the northeast monsoon, in the words of the Australian master mariner and unwearying Indian Ocean traveler Alan Villiers, “is as gracious, as clear, and as balmy as a permanent trade … the southwest is a season of much bad weather.” So it was occasionally necessary in parts of the ocean for sailing ships to use the northeast monsoon for their passage in

both

directions. But the

Arab, Persian, and Indian dhows

*

could well manage this, with their huge lateen rigs lying as close as 55 to 60 degrees in the direction of the soft northeast headwind—sailing right into it, in other words.

†

This is almost as good as a modern yacht and a considerable technical achievement. The importance of it was that India’s southwestern Malabar coast could be reached from southern Arabia by sailing a straight-line course, even if it did involve the discomfort of what seamen call “sailing to weather.”

Despite the occasional ferocity of the southwest wind, the discovery of the monsoonal system, which so easily favored trip planning, nevertheless liberated navigators from sailing too often against the elements.

1

So the Indian Ocean did not—at least to the same degree as other large bodies of water—have to wait until the age of steam to unite it. From a sailor’s point of view the wholesale shift in wind direction twice a year over such a large area is fairly unique. Elsewhere, the winds shift in strength and somewhat in direction with the seasons, but not to the degree of the Indian Ocean monsoons. The other major ocean breezes, the northeast and southeast trades in the tropics and the westerlies in the middle latitudes, remain throughout the year, as do the doldrums around the equator.

Thus, it may have been here off the coast of southern Arabia, with its clear starlit nights, plentiful stores of fish, and virtual absence of rivers, where the art of open-water sailing developed.

2

Both East Africa and India were remarkably close in terms of sailing time. Indeed, the winds have allowed the Indian Ocean from the Horn of Africa four thousand miles across to the Indonesian archipelago—and all the barren stretches of desert and seaboard in between—to be for much of history a small, intimate community.

And that means, it was early on a world of trade.

I was in the region of Oman known as Dhofar, near the Yemeni border, almost in the middle of the southern shore of Arabia. It is an abstract

canvas of ocean and rock, an utter desert in the dry winter months save for the hardy frankincense tree erupting in solitude out of the ground. I cut into the bark of one, picked off the resin, and inhaled the interior of the Eastern Orthodox Church. But long before the emergence of Christianity, burning frankincense

(lubban

in Arabic) was used to freshen family clothes, bless people, keep insects at bay, and treat many ills. Lumps of the resin were added to drinking water to invigorate the body, especially the kidneys; it was thought to kill disease by activating the immune system and warding off evil spirits. Frankincense sweetened every funeral pyre in the ancient world and was used to embalm pharaohs. This resin was found inside the tomb of Tutankhamen in Luxor, and we know it was stored in special rooms under priestly guard in the Hebrew temple at Jerusalem.

Intrinsic to the Roman, Egyptian, Persian, and Syrian lifestyles, frankincense was to antiquity what oil is to the modern age: the basis for economic existence, and for shipping routes. Dhofar and nearby Yemen exported three thousand tons of the resin annually to the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean.

3

Sailing ship after ship laden with frankincense, aided by the sure and steady monsoon winds, traveled southwestward toward the entrance to the Red Sea, en route to Egypt and Rome, and eastward to Persia and India. Months later, when the winds shifted, the ships returned to Dhofari and Yemeni ports, loaded now with ivory and ostrich feathers from Africa, and diamonds, sapphires, lapis lazuli, and pepper from India. Tribal maritime kingdoms in southern and southwestern Arabia—Sabaean, Hadhramauti, Himyarite—grew rich from their individual strips of this incense highway. Until about 100

B.C

. the fulcrum of trade between East and West was here, in this seeming wasteland in southern Arabia. Arabs, Greeks, Persians, Africans, and others mingled to do business amid this halfway house of transshipment in the days before direct sailings between Egypt and India.

4

The summer monsoon from the south, known locally as the

khareef

, brings rain that will turn these now desolate hillsides of western Oman where I stood a miraculous jungly green. But an even wetter climate in antiquity allowed for more fresh water and thus an urban civilization, culturally sophisticated because of the oceanic traffic. Driving along the shore, I found a stone hut where an Arab in a flowing

dishdasha

and embroidered cap brewed me tea in Indian masala style, with milk, spices, and a heavy dose of sugar. Earlier, in a small restaurant, I had coconut

mixed with curry powder and the local soup flavored with chili peppers and soy sauce—again the mundane influences of India and China here in Arabia, for I was closer by sail to the mouth of the Indus than to the mouth of the Euphrates.

I visited the crumbly ruins of Sumhuram, a wealthy Dhofari port at the heart of the frankincense trail, one of the wealthiest ports in the world between the fourth century

B.C

. and the fourth century

A.D

. Inscriptions at the temple of Queen Hapshetsut in Luxor mention the Al Hojari variety of white frankincense from here, considered the best in the world, and mentioned by Marco Polo in his

Travels.

5

This frankincense was famous as far as China.

At one point the Chinese city of Quanzhou imported almost four hundred pounds of frankincense per year from Al-Baleed, another Dhofari seaside settlement near Sumhuram, whose city wall encloses the remains of more than fifty mosques from the medieval age. The ruins at Al-Baleed are more extensive than those at Sumhuram, allowing me to mentally reconstruct the great city that it was. A major settlement from as far back as 2000

B.C.

, Al-Baleed was visited by Marco Polo in 1285 and twice by the Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta, in 1329 and 1349, both of whom arrived and departed by sea. The Chinese admiral Zheng He sailed his “treasure ships” across the Indian Ocean to Al-Baleed in 1421 and again in 1431, where he was received with open arms.

*

Writing much earlier, in the late tenth century, the Jerusalem-born Arab geographer Al-Muqaddasi calls ports in Oman and Yemen the “vestibule” of China, even as the Red Sea was known as the Sea of China.

6

Going in the other direction, Omanis from Dhofar and other regions of southern Arabia had been arriving in China since the middle of the eighth century

A.D

. In later centuries, a population of Arabs from the Arabian Peninsula would make the northwestern Sumatran port of Aceh, at the other end of the Indian Ocean in the distant East Indies, the “Gateway to Mecca.”

7