Moonshot: The Inside Story of Mankind's Greatest Adventure (13 page)

Read Moonshot: The Inside Story of Mankind's Greatest Adventure Online

Authors: Dan Parry

Tags: #Technology & Engineering, #Science, #General, #United States, #Astrophysics & Space Science, #Astronomy, #Aeronautics & Astronautics, #History

BOOK: Moonshot: The Inside Story of Mankind's Greatest Adventure

10.14Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

With the major Apollo development now work in progress, by 1963 the spiralling costs of the programme were causing concern for President Kennedy, whose personal interest in space was less than whole-hearted. Looking for ways of cutting the budget, in June he approached the Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev, according to his son Sergei, with a view to sharing a 'joint venture' in space exploration. At the time the Russians were leading the way in space technology and rejected Kennedy's proposal. In the autumn of 1963, this time armed with the promise of funds from Congress, Kennedy tried again. On 20 September he addressed the General Assembly of the United Nations, saying, 'there is room for new co-operation, for further joint efforts in the regulation and exploration of space. I include among these possibilities a joint expedition to the Moon. Space offers no problems of sovereignty.'

21

This time the Russians were more receptive to the idea, although some in Kennedy's own team were less committed. 'I didn't know what the president was planning,' Gilruth later said.

22

On 21 November, Kennedy joined Gilruth in Houston on an inspection of the Manned Spacecraft Center, still under construction. The site had been selected for political reasons involving Albert Thomas, a local Congressman. That night, at a dinner in honour of Thomas, Kennedy said, 'Next month, when the US fires the world's biggest booster, lifting the heaviest payroll into...that is, payload ...' The president paused. 'It will be the heaviest payroll, too,' he grinned.

23

He was never to witness it himself, of course. Thomas was still with the presidential party when Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas the following day.

Kennedy's death was almost as significant for NASA's efforts to reach the Moon as his initial speech to Congress. Beyond the questions and controversies surrounding his murder, America moved quickly to honour the memory of its fallen president. In 1963, Florida's Cape Canaveral was renamed Cape Kennedy and NASA's Launch Operations Center became the Kennedy Space Center. Kennedy's lunar ambitions lay at the heart of the legacy of a president who had become the most talked-about man on the planet. NASA could not let him down.

Lyndon Johnson, who at the end of the 1950s had done so much to bolster America's position in space, took over the presidency, and after being re-elected in 1964 he continued to support NASA's ambitions. Under Johnson, Gemini achieved its objectives and America took a lead in the space race. He even felt comfortable enough to join the Russians in supporting a treaty preventing any country claiming sovereignty over the Moon. In fact he had no choice. Military action in Vietnam was escalating, and in order to pay for it Johnson had to curb the soaring costs of space exploration. Soviet and American presentations on the use of space were given to the United Nations in June 1966, and these were later merged into an agreement that became known as the Outer Space Treaty.

24

Outlawing any military posturing in space, the treaty also promoted goodwill on the ground by requiring the safe return of any astronaut or cosmonaut who landed in what might otherwise be considered hostile territory. On Friday 27 January 1967, the agreement was simultaneously signed in London, Moscow and Washington.

A ceremony in the East Room at the White House was attended by Vice-President Hubert Humphrey and Secretary of State Dean Rusk, along with the ambassadors of Russia and Britain, together with other international VIPs and a handful of astronauts, including Armstrong.

25

At 5.15pm, President Johnson began the formal part of the proceedings with a speech in which he declared that the treaty would preserve peace in space. He added, 'It means that astronaut and cosmonaut will meet someday on the surface of the Moon as brothers and not as warriors for competing nationalities or ideologies.'

26

Whether there would be cosmonauts there to greet them or not, Johnson was optimistic Americans would indeed walk on the Moon.

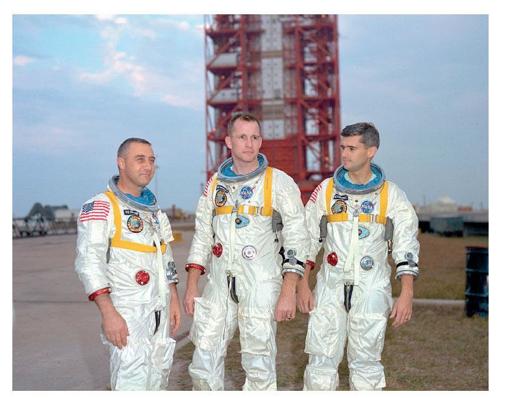

He could afford to be. A new type of spacecraft, capable of a lunar mission, was scheduled to launch in three weeks' time, and even as Johnson spoke three astronauts were down at the Cape testing its systems. Sitting in the middle seat of the prototype command module was Ed White, preparing for his second flight into space. On his left sat the mission commander, Gus Grissom, who had flown the second Mercury flight and later led the first Gemini mission. The third member of the team was new recruit Roger Chaffee. Together, the men were checking the spacecraft's electrical systems in preparation for a 14-day test-flight. The biggest manned spacecraft NASA had yet built, the command module contained many more systems than Gemini; its development had been repeatedly held back by its complexity. In the weeks before the test, Grissom had grown frustrated with the delays and technical problems, particularly those disrupting the communications system which was prone to interference from static. That morning, Joe Shea, the manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, had tried to persuade Grissom that the problem was under control. But according to Deke Slayton, Gus wasn't convinced. 'If you think the son of a bitch is working,' Grissom reportedly told Shea, 'why don't you get your ass in the cabin with us and see what it sounds like.' Declining Gus's invitation, Shea joined Deke in a concrete blockhouse 1,600 feet from launch-pad 34, where the spacecraft sat on top of its empty Saturn IB rocket.

27

The so-called 'plugs out test' involved an assessment of the spacecraft under its own electrical power. This was to be done under simulated launch conditions, which meant the cabin would be filled with 100 per cent oxygen. The crew, wearing pressure -suits, were strapped into their couches at 1pm, and after technicians resolved a problem with the life-support system they closed the spacecraft's elaborate hatch. Consisting of three separate layers, it couldn't be removed in less than 60 seconds. Once sealed shut, the cabin was flooded with oxygen until the pressure reached 16.7psi – 10 per cent higher than normal conditions at sea level. As a simulated countdown began, the astronauts tried to talk to the operations room. Later they would be in direct contact with Mission Control, 900 miles away, but with static clogging the line Gus was having trouble talking to anyone. 'If I can't talk with you only five miles away,' he snapped, 'how can we talk to you from space?'

28

The problem seemed to clear up, but at 6.20pm, ten minutes from zero, communications failed again, and as dusk descended the countdown was put on hold.

At the White House, the treaty had been signed and Johnson and his guests were attending a reception in the Green Room.

29

While Armstrong mingled with the crowd, Grissom and his crew struggled to complete their tests. They had been sitting in their spacecraft for more than five hours and in that time oxygen had permeated everything inside the cabin. The polyurethane foam covering the floor absorbed oxygen like a sponge, as did the 34 feet of Velcro which was stuck on the walls to secure objects in weightlessness. Elsewhere lay flammable bags, netting restraints, logbooks and more than 15 miles of wiring, much of which had lost its protective layer of Teflon insulation after engineers had worn it away while repeatedly working inside the cabin.

At 6.30pm, defective wiring short-circuited under Gus's couch, producing a spark that quickly developed into a fire. In an oxygen-rich environment, Velcro explodes once ignited; even a solid bar of aluminium burns like wood. As flames raced up the left-hand wall of the cabin, medical telemetry showed that Ed's pulse suddenly jumped. Grissom cried 'Fire!' on the radio; then Chaffee said, 'We've got a fire in the cockpit,' swiftly echoed by White.

With flames consuming the oxygen relief valve, making it impossible to depressurise the cabin, Gus released the straps of his harness and moved over to help Ed with the hatch. Seconds after Grissom's cry had alerted those outside, a pad technician watching a television monitor believed he saw Ed reach over his left shoulder and bang the hatch window with his gloved hand. Fuelled by the oxygen, the foam, the Velcro, sheets of paper and other materials, the fire leapt across the hatch window, burning with increasing intensity. As flames destroyed the life-support system, a flammable solution of glycol cooling-fluid sprayed across the cabin, producing thick clouds of toxic gas once ignited. While Grissom and White struggled with the hatch, Roger Chaffee – who was furthest from the seat of the fire – stayed where he was and tried to maintain contact with the outside world. 'We've got a bad fire – let's get out. We're burning up,' cried Chaffee, followed by an unidentifiable scream that froze the blood of all who heard it. Then, less than 17 seconds after the first cry was heard, came silence.

As the temperature inside the cabin reached 2,500°F, the rising pressure tore open the hull of the command module, releasing sheets of flame and preventing any immediate efforts to attempt a rescue. For five minutes no-one could get near the inferno. Eventually, wearing gas masks and fighting their way forward using fire extinguishers, technicians were able to get close enough to open the hatch. Among the first to look inside was Deke, who had rushed over from the blockhouse. He described the scene as 'devastating ... the crew had obviously been trying to get out ... [the] bodies were piled in front of the seal in the hatch'. Asphyxiated, and suffering third-degree burns, Grissom, White and Chaffee had fallen into unconsciousness long before anyone had been able to reach them.

30

News of the fatal tragedy quickly spread. While Deke was inspecting the cabin, Neil was in a taxi returning to his hotel. By the time he got to his room, at around 7.15pm, a message was waiting for him requesting him to call the Manned Spacecraft Center. In Houston, the Astronaut Office asked Janet to go to Pat White's house and keep away from the television until someone could get over to her.

31

That evening Neil and fellow astronauts Gordon Cooper, Dick Gordon and Jim Lovell

32

broke open a bottle of Scotch as they discussed the loss of their friends. For Neil, 'it really hurt to lose them in a ground test ... it happened because we didn't do the right thing somehow. That's doubly, doubly traumatic.'

33

While Roger was new to NASA, Gus was known by everyone. But it was the loss of Ed that Armstrong found particularly hard. Many years later, in reference to the 1964 house fire, Neil said, 'Ed was able to help me save the situation, but I was not in a position to be able to help him.' Ed White was buried at West Point on 31 January, and both Armstrong and Aldrin were among the pallbearers. For Neil, the event was especially difficult: it was five years to the day since Karen's funeral.

One of three X-15 rocketpowered aircraft, carried aloft under the wing of a B-52.

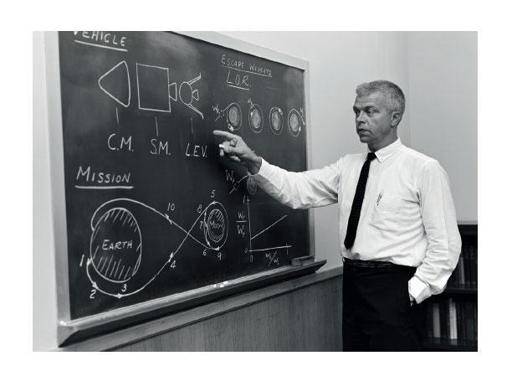

John Houbolt explaining lunar orbital rendezvous. His ideas were initially rejected by NASA but proved vital to the lunar landing.

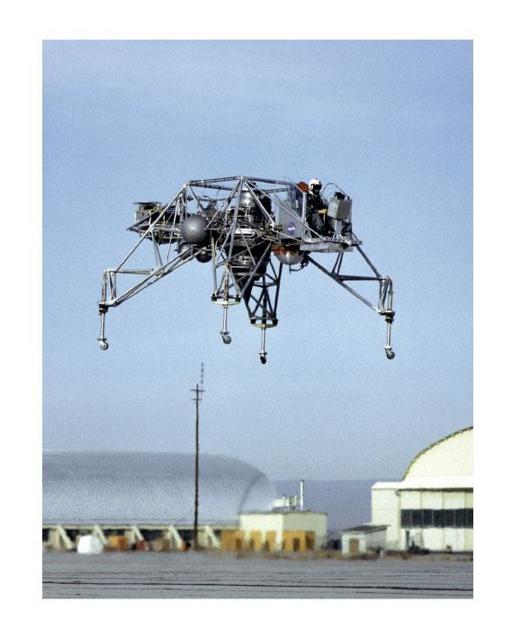

A lunar landing research vehicle at Edwards Air Force Base.

Other books

It Feels So Good When I Stop by Joe Pernice

Redemption (MC Biker Romance) by Wilde, Blakeley

Harmony by Mynx, Sienna

El perro canelo by Georges Simenon

Ashes Under Uricon (The Change Book 1) by Kearns, David

Warriors Don't Cry by Melba Pattillo Beals

Thirty-Two and a Half Complications by Denise Grover Swank

Bare by Morgan Black

A Bloom in Winter by T. J. Brown

Denying the Wrong by Evelyne Stone