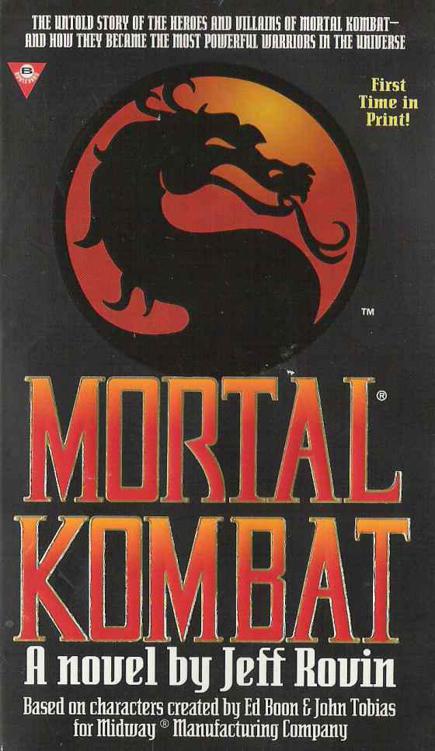

Mortal Kombat

Authors: Jeff Rovin

Jeff Rovin

"I have decided," Shang Tsung said, "to, ah – take the year off. I'm no longer young, Kung Lao, and felt it would be best for this year at least to let someone else fight on my behalf."

The thundering grew louder as a great and hulking shape began to emerge from the darkness. It was vaguely human in form, but stood over eight feet tall and had – it appeared – not the usual complement of limbs, but more.

The bronze-skinned entity roared, the uppermost of its four powerfully muscled arms thumping its great chest, the lower two reaching impatiently toward Kung Lao. The muscles of each of the four forearms strained against the iron wristbands by which it had been kept manacled, and every one of the three thick fingers on the two lower hands curled, aching for combat.

Shang Tsung's eyes gleamed wickedly. "Kung Lao – I would like to introduce you to my champion. However, if you can speak hereafter, you are free to call him by his given name: Goro."

Apart from the characters that appear in the videogame Mortal Kombat, most of the gods, dragons, heroes, alchemists, curs, and folk characters described or mentioned in this novel come from the rich mythology and history of China. Interested readers can learn more by consulting such texts as

Great Civilizations: China

by Ian Morrison and the wonderful

Alchemy, Medicine and Religion in the China of

A.D. 320

, in particular the James R. Ware translation.

The roots of a thing may be well balanced, but its branches may be deviant.

The Nei P'ien of Ko Hung

A.D. 320

In the beginning of time, nothing was everywhere and it was everything.

There was no matter and no change. Whether this lasted for the briefest moment or countless eternities is impossible to say, because time did not exist.

And then P'an Ku appeared.

It is said that the deity simply willed himself to exist. True or not, the birth of the god marked the beginning of all things physical, the start of growth and change and decay – the beginning of time. In what may have been an instant or an aeon, P'an Ku himself grew strong and aged and died.

Upon the god's death, the parts of his body, like patchwork children, came alive. Possessed of wills and spirits of their own, they loosed themselves from the whole. His left eye became the sun, his right eye the moon. Wrapped around his heart, which began to beat anew, his flesh transformed itself into the living earth, the rivers formed from his blood, and his hair became the forests, from the tallest trees to the laziest grasses. P'an Ku's dying breath encircled the globe of his skin and became the wind; his last, mighty groan became the thunder. His great and noble soul settled in the vault of the heavens, took on form and substance, and became the supreme six-armed, four-legged god T'ien.

Simply by the act of thinking it, T'ien created the other gods, and the gods – a gaggle of mighty and egotistic beings – soon became bored and created beings on the flesh of P'an Ku. Their individual creative powers brought forth all manner of four-legged and winged and seagoing animals, creatures that fought and ate, loved and suffered, lived and died. But before very long the simple routine and desires of the varied beast-races failed to keep the gods entertained, and so they created people.

Some of the gods were merely amused and diverted by the antics of the complex, scurrying new creatures they'd wrought. Others found them compelling, for while their actions were very much like the animals that came before them, many had the will and desire to be different... more spiritual, more like the gods who had created them.

From his place in the heavens, T'ien looked with interest and compassion on the actions of newborn humankind. So with a blast from his nostrils, he sent the winds that moved the clouds that carried the rains that nourished the rice fields that fed the people of Earth. And his human subjects revered him for this. Seeking and finding the origin of the winds – a tale to be told another time – they declared Mt. Ifukube in the region of Guangdong in southeastern China to be his holy mountain.

T'ien was not angry when his home had been discovered, for the gods had made humans curious. But he sent out messages in dreams, and in these visions he bade a select group of wise men and women to come and watch over his mountain, to see that no mortal approached the lower peaks where the lesser gods lived... or tried to find a way past them to his own abode. Should any succeed in such an endeavor, T'ien vowed that to punish the impertinent he would stop the winds that fed the masses.

Fifteen souls heeded the summons, coming from different regions of the land and settling in caves in the foothills of Ifukube. Coming to them again in dreams, the master god made his high priests immortal and gave them laws which they disbursed to lesser priests. And through the centuries, though pilgrims came to adore the mountain and pay homage to the god, and passers-by looked with wonder from a great distance, none dared climb it.

Over time, the cloud-piercing mountain occasionally rumbled with Tien's displeasure, sometimes glowing red with his anger, now and then blazed with the reflected glow of his contentment. When he was at peace, it anchored the tranquil beauty of a rainbow.

Five thousand years ago, the wealthy and grateful Yellow Emperor of the Flowery Kingdom erected the first temple to a god. He did not feel worthy enough to honor T'ien himself, so he erected the Shrine of Shang Ti, God of the Mountains and the Rivers. Soon, other rulers built temples to different gods, though never to T'ien. And it became an unspoken law that, while T'ien's eight-limbed form could be represented in clay and in ink, his face would never be rendered or even described in words. For how could humans hope to capture and convey the radiance and wisdom and eternal nature of Tien's eyes and mouth, the carriage of the great head?

Yet artists and holy people debated what T'ien must look like, and a few sought to describe him by rendering the handsome and magical features of the lesser gods, posting these paintings in villages, and allowing everyone from scholars to poets to laborers to write verse beside them, ideas on how individuals might picture T'ien in their mind's eye, or could contemplate his image by contemplating the many ways in which the god nurtures the world:

Look at these eyes and imagine them deep.

Life comes when they open, death when they weep.

Are there two lips that speak mightier words

On whose wings souls can soar higher than birds?

His nose moves the air that nourishes all,

The seeds in the spring; the frost in the fall.

Over centuries, the religion of T'ien grew, and the honoring of him through oblique art and poetry became both a passion and recreation among many people. Most accepted that not only was it forbidden to know the face of T'ien, but that his face was probably unknowable – like the blazing visage of the sun, or the hidden side of the moon.

Most accepted this... but not all.

Further, they wondered about the much older god, whose heart beat at the center of our world.

Priests of the many sects that honored T'ien came to believe that the chambers of the heart radiated auras that were white, black, blue, or red.

The blue chamber was the passage to our world.

The white opened into the realm of T'ien.

The black was the passage to the abode of the dead.

And the red –

The red was the doorway to the Outworld, home of the greatest mysteries of all.

Chu-jung in the District of Tan-Yang:CHAPTER ONE

A.D. 480

"But

why

must you do this?" Chen wailed as she clutched her nephew's arm through the sleeve of his brown robe. "Do you even know?"

Kung Lao's handsome features twisted unhappily. "I do know, Aunt Chen," he said. He stopped walked toward the door of their bamboo hut and wormed his arm gently from shoulder to wrist in an effort to dislodge her. "I go to learn."

"Would you also walk into the lake to learn how to drown?" she asked, holding fast. "Would you hurl yourself from the roof of the temple in Jackichan to discover that you cannot fly?"

Kung Lao frowned. "It isn't the same thing. I have

seen

people drown, and I know that I'm not a bird or butterfly. But I have never seen a god."

"And you

won't

!" she screamed. "You'll die before you reach even the lowest ring of gods."

"How do you know," he asked, "if no one has ever tried? The priests didn't die."

"The priests don't try to climb the mountain," she said, tears spilling from her narrow eyes down her wrinkled, weather-beaten cheeks. "Besides, the holy ones were summoned. You were not. You finished making water deliveries, stopped in the village square, and decided, 'Ah... it's time that I, lowly Kung Lao, who carries water from the well to the buckets of my people, go and have a talk with T'ien.'"

"It was more than that," said that tall, powerfully built youth, his frown deepening.

"Yes," she said. "Madness the size of Mt. Ifukube!"

"No, my aunt," Kung Lao replied. He grabbed the long queue of black hair that hung down his back and held it in front of his aunt. "Tell me – what do you see?"

She regarded him strangely. "I see... my mad nephew's hair."

"What else?" He wagged the end at her.

"I see a white cloth tied around the end, instead of the black one you usually wear." She looked into his eyes. "I don't understand–"

He shook his head. "I can't explain."

Chen took the youth's hands and squeezed them tightly. "Why must you be your father's son," she asked, "blessed with curiosity but ungoverned, unwilling to hear reason? I lost him, I lost your uncle. I don't want to lose you!"

"And you won't," he promised. "My father was hasty, I am not. Wasn't it I who warned him not to mix those powders and set them afire?"