Mr Briggs' Hat: The True Story of a Victorian Railway Murder (32 page)

Read Mr Briggs' Hat: The True Story of a Victorian Railway Murder Online

Authors: Kate Colquhoun

Tags: #True Crime, #General

Sketches of some of the witnesses from an illustrated newspaper circa 1914.

Left to right:

John Death the silversmith, cabman Jonathan Matthews and his wife.

The cell for condemned prisoners, Newgate, 1850.

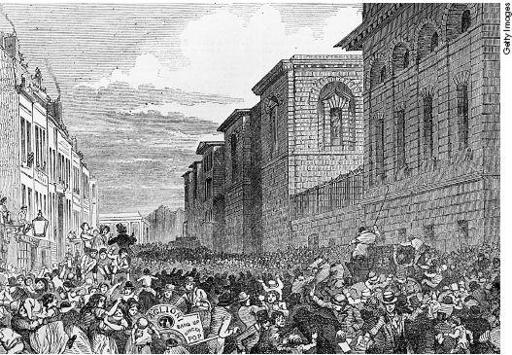

Crowds throng the Old Bailey to witness an execution at Newgate, 1863.

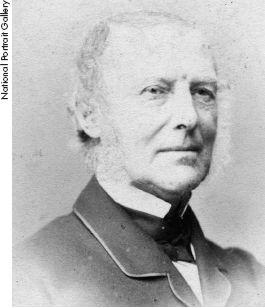

Sir George Grey, Home Secretary.

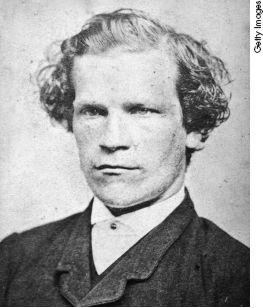

Franz Müller, 24, German tailor.

‘Dead Man’s Walk’, the underground passage between Newgate and the Old Bailey through which Müller walked on each day of his trial, and where his body was buried.

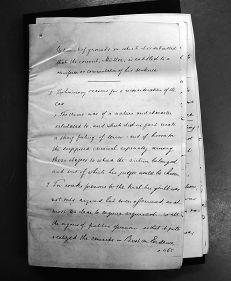

The Memorial on Müller’s behalf, delivered to Sir George Grey by solicitor Thomas Beard.

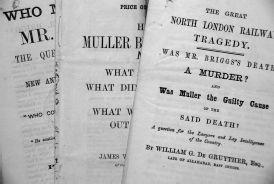

Some of the many pamphlets printed after Müller’s trial.

Thomas Lee’s evidence was known to be crucial to Müller’s defence. When the trial reopened on Saturday 29 October, he was Parry’s first witness.

Lee’s story was unwavering. As the 9.45 p.m. train from Fenchurch Street arrived at Bow Station on the night of 9 July, he had spoken briefly to Thomas Briggs.

How long had you known Mr Briggs?

For about three or four years, I should think.

When did you last see him alive?

On 9th July, Saturday evening, at the Bow Station, in a first-class carriage, about ten o’clock, I think – it was a carriage of a train coming from Fenchurch Street – it stopped at the Bow Station. It was about three or four carriages from the engine, I think.

Did you speak to him?

I said, ‘Good-night, Mr Briggs.’ He answered, ‘Good-night, Tom’ – he was sufficiently intimate with me to call me in that way.

Was anyone else with him?

The train stopped rather longer than usual that night … there were two persons in the same compartment of the carriage with Mr Briggs. There was a light in the carriage. I believe Mr Briggs had his hat on, or else I should have noticed it; I should have noticed it certainly. One of the persons was sitting on the side of the carriage, next to the platform, opposite Mr Briggs, the other was sitting on the left-hand side of Mr Briggs, next to him, on the same side of the carriage.

Did you see them clearly, then?

I saw sufficiently of those two persons to be able to give a description of them afterwards, one in particular – the man who sat opposite Mr Briggs – was a stoutish, thick-set man with light whiskers, and he had his hand in the squab or loop of the carriage, and it was rather a large hand. I had only a casual glance of the other man: he appeared a tall, thin man, dark.

And to the best of your judgement, is the prisoner either of these two men?

I would not swear that. I should rather think he was not.

When the defence finished its questions, the jury had one of its own to add. When Mr Briggs travelled late on the railway, Lee had stated that he often slumbered between stations. Was he in the habit of having his hat on, or off, they asked.

He used to have it on

, said Lee. The jury might have wondered, therefore, why Briggs’ silk hat was not also crushed by the blows from his assailant.

Collier stepped forward to cross-examine. Lee was a powerful witness and Collier went straight for the one weakness in his testimony – that he had not come forward voluntarily and that it had taken more than a week for him to tell the police what he had seen. He urged Lee repeatedly to tell the court where he had been that evening and why. Lee refused to be mauled, remaining stalwartly unemotional as he replied,

I went to Bow for amusement

.

Why did you not give information to the police as soon as you heard of the murder?

I did not wish to be bothered.

You did not wish to be bothered?

I did not consider my evidence material. I did not see that there was any need

.

Despite Collier’s expressions of disbelief, Lee adhered to his contention that, once asked to testify, he had done so willingly and honestly and that he was as sure now about what he had seen as he had been three months before.

Parry’s next witnesses were two second-hand hat dealers who testified about the fashion among young men for ‘cut-down’ hats. One said that stitching them down was common and the other concurred. Both added that a stitched hat would sometimes be varnished with gum or shellac but that it added to the expense. Their evidence confirmed what Parry had already established in his cross-examination of Digance: that hats like the one found in Müller’s box were a fixture of the second-hand market.

To establish Müller’s alibi, Parry needed to call only four more witnesses. The first was Alfred Woodward, a clerk for the Electric and International Telegraph Company. Woodward’s records showed that a telegraphic message was delivered to Müller’s friend Miss Eldred at Stanley Cottage, James Street, Vassall Road in Camberwell during the afternoon of 9 July.

Next Parry examined Mrs Elizabeth Jones, a small-time brothel keeper, and Mary Anne Eldred, a young woman who lodged with Jones and who, she said, had received regular visits from Franz Müller for nine months prior to the date of the murder. Mrs Jones testified that on the day the telegram was received Miss Eldred had gone out at her habitual hour – nine o’clock in the evening – narrowly missing the arrival of Müller who had hung about for ten minutes or so before leaving to walk the three-quarters of a mile back to the nearest omnibus stand at Camberwell Gate. She told the court that this journey would normally take between fifteen and twenty minutes and she repeated that she remembered very clearly that Müller had called on the

day the telegraph arrived for Mary Anne; he had been lame and wore a slipper. Responding to a question put directly by a juror, she confirmed that Müller had been wearing a hat.

Jones’ testimony appeared to establish that Müller had been in Camberwell at ten past nine on 9 July, but her profession presented a difficulty. Under cross-examination the prosecution bullied her remorselessly, chipping away at the reliability of her memory and that of her kitchen clock. Was this the kind of woman, they imputed, the court should believe?

Then came Müller’s ‘girlfriend’, Mary Anne Eldred, who took the stand shaking visibly and who was so profoundly deaf that it was only by speaking very slowly and loudly that Parry could make his questions understood. She stated that Müller visited her often and that he had asked her to go to New York with him several weeks before 9 July. She said that she always left the house at nine o’clock in the evening. Asked about the telegram, she told Parry that she had only remembered about it ten days earlier: gentlemen from the GLPS had been to see her in an attempt to fix Müller’s alibi and had prompted her memory. It had taken her a while to find it, but when she did, the paper was sent directly to Thomas Beard since it proved the date of Müller’s last visit. Cross-examining, Collier was brutal. What time did you dine that day? When did you breakfast? What time did you get up? When did you go to bed? To each question she stammered,

I don’t remember, I can only guess, I can’t exactly tell

. Under the Solicitor General’s furious onslaught, Eldred’s initial appearance of certainty began to crumble.