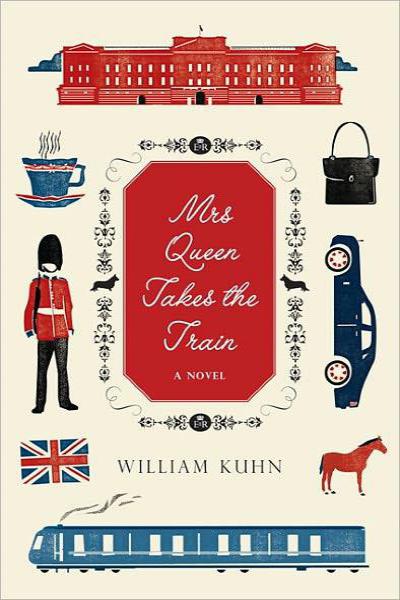

Mrs. Queen Takes the Train

Read Mrs. Queen Takes the Train Online

Authors: William Kuhn

Mrs Queen Takes the Train

A Novel

William Kuhn

www.harpercollins.com

For Fritz Kuhn

S

everal years ago, on a dark afternoon in December, Her Majesty Elizabeth the Second, by the Grace of God, of the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland, and Her Other Realms and Territories Queen, Head of the Commonwealth of Nations, Defender of the Faith, Duchess of Edinburgh, Countess of Merioneth, Baroness Greenwich, Duke of Lancaster, Lord of Mann, Duke of Normandy sat at her desk, frowning at a computer screen. The desk had once belonged to Queen Victoria. Its surface was polished but uneven, like many other pieces of furniture in Windsor Castle, so the computer keyboard wobbled when The Queen pressed on it. She folded a piece of paper into a tiny square and slipped it underneath a corner.

The keyboard was one thing, but the computer itself was another. She expected it to work, but in her experience it was just as bad as the keyboard, though the reasons were more mystifying. It was always locking up just when she found something she thought she might like to see. She had been instructed to look for the cursor when this happened. Even though the young woman who handled information technology for the Privy Purse had helped her increase the magnification of the screen, her diminished eyesight made it difficult to find the tiny flashing bar, which she understood she was meant to move around with the mouse, which wasn’t a mouse at all, of course. Why was it called that? She pressed what she took to be an appropriate key and the screen changed color. She tried another and the document she’d been working on (a memoir of her favorite horse, Aureole, who’d nearly won the Derby in 1953) disappeared. She punched a third and the computer emitted a startled

beep

. She sat back against her chair and sighed with frustration.

She had already called the IT woman three times. She couldn’t call her again. The Queen knew she needed help, but she hated to appear helpless. Everyone around her seemed to know what they were doing on the computer. She was the only one who didn’t. When computers had first begun to be commonplace she thought she could leave them to the experts. Pen and ink and paper would see her out. She wouldn’t need to learn. But she was wrong. Now it wasn’t only the young who consulted the computers that were apparently inside their mobile telephones, it was also the butler who entered her choices for luncheon on a computer in the cupboard, the private secretary who communicated with Number 10 via what was called instant messaging, and even the Mews posted online films of mares foaling. It had dawned on her that she was going to have to learn the language if she didn’t want to be left behind. She had had what she thought of as endless lessons. And still, learning how to manage the machine was more difficult for her than learning Chinese. She’d learned a few words of that with no trouble for the Chinese state visit a few years ago.

She stood up from her desk and looked out the window, up the Long Walk in the Home Park toward the statue of King George III. An old Boeing 747 which had just departed from Heathrow lumbered into the air above the Castle, rattling the windowpanes. The sound was briefly deafening. The Queen had grown so used to this that she seldom noticed. She supposed that if one’s back door opened onto the railway into Waterloo, one also became accustomed to the noise of the trains. When the wind was in the northeast, the air traffic controllers always sent the planes taking off over Windsor. She didn’t mind the noise. It was like a mini weather report. When she did notice the aeroplanes, three minutes apart, she thought to herself, “Ah, wind from the northeast.” No, the noise didn’t bother her, but something about being thwarted by the computer, and the impossibility of asking for more help, did bother her. She felt tired. She sat down dispiritedly in one of the chairs next to the unlighted fire. “Oh, Little Bit,” she said to herself, “what now?”

People had been writing about her from the very day she was born in April 1926. The newspapers had reported her learning to talk. “Lilibet,” they wrote, was one of her first words, a small child’s pronunciation of her own name, Elizabeth. That was entirely wrong, as reports about her often

were

wrong. Actually, it came from a cake that she had been served one teatime in the nursery. It had pink, raspberry-flavored icing. Her eyes lit up when she saw it. Nanny told her she might only have “a little bit” of the cake if she were a good girl. “Lilibet! Lilibet!” she’d cried and Nanny had reported this to her mother. “Lilibet” had nothing to do with Elizabeth, but it was a name that had stuck, and she’d grown up with it as the diminutive people in her family persisted in calling her. It was a tease really, a pinch, a reminder that it was undignified for a princess to be greedy for cake, not the sweet nickname people thought it was. Nevertheless, she even used it with herself from time to time, especially when she blamed herself for doing something wrong. She forgave Nanny for telling her mother about the cake as she connected the one with treats and the other with teases. She could recall Nanny taking her on the train to Sandringham all by herself one Christmas. What a treat that was!

[Edward G. Malindine/Hulton Royals Collection/Getty Images]

Sometimes it amused her to pick up a recent biography and to annotate it. The librarian had once shown her some nineteenth-century biographies in the archives that her great-great-grandmother had annotated. Queen Victoria had written in the margins, in her distinctive sloping hand, “I never did,” or “Not true,” alongside the passages to which she objected. Inspired by the example of her predecessor, The Queen would correct errors in the margins herself. Lately, however, she hadn’t the energy. Did it matter to get things right anymore?

She knew that sitting alone in her chair, thinking gloomy thoughts, and staring blankly off into space made things worse, but she couldn’t help it, no more than she could have stopped eating the pink cake if Nanny hadn’t been there to prevent her when she was a little girl. Only her internal nanny told her that sitting alone in her chair doing nothing was bad for her. Still, the part of her that felt rather sad was stronger than her internal nanny, more than a match for her, really.

No one had warned her that she might lose confidence as she grew older, and it was true that many of the things she’d known how to do formerly without a second thought, such as asking for help, she couldn’t bring herself to do now. She also worried more than she used to. A sheet of paper delivered the evening before to her sitting room with the coming day’s list of engagements sometimes made her lose sleep. She wondered what would happen if a Lady Mayoress chatted too much at the unveiling of a plaque and made her late for the luncheon at the factory she was scheduled to visit next. Would they lose patience with her, as she nowadays sometimes lost patience with herself?

Enough of this. Nanny suddenly got the upper hand. She shook herself out of her fit of anxiety and heaved herself out of the chair. She stalked toward the computer on the other side of the room as if it were game and she meant to shoot it. A sudden burst of creative energy gave her an idea. She reached over and turned the damned thing off. Then, a moment later, she turned it on again. She suddenly recalled the woman from IT doing this. “Yes,” she said under her breath, “turn it

off

. Then on again.” The machine whirred into action, flashing several screens which she could not in the least comprehend. After several moments, however, a screen appeared that did look familiar. It had several vertical rows of symbols on it. She recognized the symbol for the Web browser: she knew if you clicked on that you could what was called “surf the net.” The IT woman had a bit of Italian and had told her the Italians said “

navigare in rete

,” which The Queen liked better, as she silently amended it to an Italo-English pidgin phrase, “navigate in rot.” That’s what she liked to think of the so-called wonders that were available online, a lot of rot.

It was Prince Edward who’d begun to indicate a few things on the computer that were not rot. First he’d shown her the website of the Household Cavalry. Splendid young men. Scarlet tunics. Groomed mounts. Brave boys. Then he’d shown her a page for the Royal Mews, where a mare was giving birth to a foal. He’d shown her a little place on the right-hand side of the screen where you could move the cursor, press it, and then a short video of the foaling would play. Superb animals. Remarkable little film. He’d also shown her (he knew his mama’s bad habits) a website where she could place a small bet on the races. The site itself was too complex for her to understand entirely, but she kept coming back to it, studying the race meetings, the odds, and the names of the runners, promising herself that one day she might place a small bet, no more than five pounds.

Prince Edward had also shown her how to save websites, under a heading at the top of the screen labeled “Bookmarks.” He’d shown her how to save places there for Google and Twitter, which she silently called “Mr Google” and “Miss Twitter,” as their names seemed to have been invented for a nursery story. He’d also called up different screens for Yahoo and Facebook. She didn’t see the point of what she called to herself “Yah-Hoo.” How was it different from Mr Google? She didn’t like to interrupt him, as Prince Edward was so evidently proud of what he was showing her. Facebook he showed her at the same time as he attempted to demonstrate what she thought he described as “cutting and pasting,” though there were no scissors. She didn’t understand that at all, confused it with Facebook, and started thinking of the two as somehow related, “Pastebook.” It made her think of being a little girl and sticking pictures into a large scrapbook with a big pot of paste.