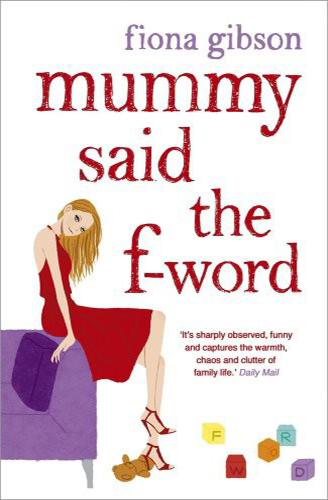

Mummy Said the F-Word

Read Mummy Said the F-Word Online

Authors: Fiona Gibson

Tags: #Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #General

Fiona Gibson is a freelance journalist who has written for many publications including the

Observer

, the

Guardian

,

Red

and

Marie Claire

. She has three children.

Also by Fiona Gibson

Fiction

Wonderboy

Babyface

Lucky Girl

Non-fiction

The Fish Finger Years

Mummy Said the F-word

FIONA GIBSON

www.hodder.co.uk

www.hodder.co.ukFirst published in Great Britain in 2008 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

Copyright © Fiona Gibson 2008

The right of Fiona Gibson to be identified as the Author

of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real

persons, living or dead is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 444 74070 7

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

www.hodder.co.uk

Contents

For Margery and Keith, with all my love

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Huge thanks to: Jenny Tucker for accidentally providing the title (thanks also to Pedro, the daddy who said the f-word). Cathy Gillian for being the best writing pal I could wish for. Tania Cheston for running with me and being so helpful with plots. The brain-boosting Dolphinton writers: Vicki Feaver, Elizabeth Dobie, Margaret Dunn and Amanda McLean. Kirsty Scott, Wendy Rigg, Anita Naik and Daniel Blythe for stacks of encouragement and perky-up emails. Jane Wright at the

Sunday Herald

for giving me the chance to be an agony aunt for a year. Wendy Varley and Ellie Stott for reading the early manuscript and offering lashings of encouragement. Chris, Sue and Jill at Atkinson Pryce bookshop. All at Hodder, especially my editors Sara Kinsella and Isobel Akenhead, and publicist Eleni Fostiropoulos. Jen and Tony at

www.bluex2.com

for my website. Finally, my gorgeous family Jimmy, Sam, Dex and Erin for always being there, making me laugh, keeping me sane and agreeing that we really are rubbish at keeping fish.

PROLOGUE

A copy of

Bambino

magazine lies on our kitchen table. I pick it up, idly flicking through, about to fling it bin-wards. ‘Britain’s weekly parenting bible,’ reads the line beneath the shimmering pink logo, as if no parent could possibly consider raising a child without it.

The magazine falls open at the problem page. ‘When Daddy Strays,’ reads the headline above one of the problems. I glance through the open door of our basement kitchen. My husband, Martin, is in the garden, talking urgently on his mobile. He has taken the day off work with life-threatening man-flu, but must be in constant contact with his office,

naturellement

. Our son Travis is enjoying the June sunshine and trying to catch butterflies to stuff into his toy ambulance.

My skin prickles as I glance back at the magazine. The agony aunt is called Harriet Pike. She is wearing an expensive-looking white shirt – the kind magazines always refer to as ‘crisp’ – and a terse smile that veers towards a sneer. In fact, she bears an uncanny resemblance to the woman who pulled a disgusted face when a nugget of dung tumbled out of Travis’s dungaree leg in the fruit shop. Cat’s-arse face. You become immune to people like that.

‘Sassy, smart – she shoots from the hip,’ reads the text along the top of Harriet’s page. I start reading the ‘Daddy Strays’ bit. Not that I expect this Pike woman to say anything useful. I’m just curious, that’s all. My friend Millie edits this magazine and is forever sending me copies, which I bin, virtually unread, although I never tell her that. Millie means well, and sends the magazines in the hope that they’ll bring some sparkle to my life, ha ha.

What Pike has done is break down the fall-out from Daddy’s affair into several steps – as if the unravelling of an entire life is as simple as baking a cake. ‘Step one’, I read, ‘is grief.’

You’re grieving for the good times, the life you had together. Yet, however much you’re hurting, bear in mind that infidelity is rarely one person’s fault. Examine your own role, the part you had to play in all of this. Perhaps he felt dreadfully neglected. Second fiddle to your new baby.

What planet is this woman on? He shagged someone else, end of story! ‘Hopefully,’ Pike witters on, ‘you might find it in your heart to forgive.’ With a snort, I drop the magazine on to the table.

A cool breeze sneaks through the open back door. Finishing his call, Martin wanders into the kitchen. I look up and he’s gawping at

Bambino

, which still lies open at the problem page. Our eyes meet. And I see it – guilt and utter terror – smeared across his face.

Shit. Something’s wrong. My heart judders, and everything around me turns vague and fuzzy as if it’s dissolving. So I haven’t been imagining it. I’m not a paranoid idiot. I’ve suspected for ages that something’s been going on – something that Martin couldn’t possibly share with me, because I am only his wife of twelve years and the mother of our three children. I’d even wondered if he’d been made redundant and couldn’t bring himself to tell me. My head had filled with images of him sitting in parks sipping coffee, trying to fill up the days.

Now, I

hope

it’s something like that. It really wouldn’t be too bad. I could work full-time, find an office job, and we’d manage OK. I’d even forgive all the lies.

Clutching his ambulance, Travis scampers in behind Martin and dances around him. He glances up at Daddy, whose face has turned an alarming purply-red. I grip the back of the chair, terrified of what might happen if I let go.

‘Caitlin, I’m so sorry.’

I watch Martin’s mouth. He never calls me Caitlin. From the start, I have always been Cait to him.

So I know it’s something very bad.

‘What … what’s going on?’ It comes out as a whisper.

Martin’s face has turned pale now, as if his internal temperature control has gone haywire. He slumps on to a chair at the table.

‘Brrrmmm,’ hums Travis, making his ambulance perform a jaunty three-point turn on the floor.

‘We can’t talk about this now,’ Martin murmurs, firing Travis a pleading look.

‘Nee-naw!’ cries our son. ‘Want butterflies. C’mon, Daddy, let’s play!’

I can’t speak. My head is filled with a dull thumping noise.

‘Daddy funny,’ Travis announces. ‘Daddy cry.’

He’s right, although Martin’s tears aren’t falling properly. They’re kind of blotting and making shiny patches around his eyes.

‘Please go upstairs, Travis,’ I murmur. ‘Go up to Lola’s room. She’s got all her vet things out.’ She, like her father, is off sick today. The house feels stale and germy.

‘No,’ Travis retorts, excavating a nostril with his finger.

‘Please. Up you go. You love playing vets. You could be chief vet! Go on, darling, I’ll come up in a minute.’ If I had it, I would stuff a million pounds into his dungaree pockets if he’d go up to Lola’s room.

‘No like Lola. No like vets.’ Travis studies his father in awe. Watching Martin crying is proving to be far more entertaining than a Junior Vet surgery with light-up X-ray machine and plastic kittens that wee in their litter tray. I pray for him to tire of this startling display and leave the room.

All these years together and I’ve never seen Martin cry. Sometimes I’ve wondered if he actually possesses tear ducts, or if they were switched off at some point during late childhood. Everything feels heightened. My heart is pounding frantically.

‘Wee-wee,’ Travis announces.

‘Whatever it is,’ I say calmly, ‘you can tell me.’

‘Cait,’ Martin mumbles, ‘there’s someone else. I’m leaving you.’

I turn away from him and stare down at Travis, whose navy corduroy dungarees are slowly darkening around the groin, indicating the steady progression of wee.

‘Mummy crying!’ he says, grinning, as if my next party trick might prove even more of a hoot. Who needs a Junior Vet surgery with all of this going on? It’s fantastic fun in our house.

I swipe my arm across my face, march towards Travis and plop him on my hip. Then I carry him out of the room, yearning to shrink myself down, squeeze into his ambulance and be taken to a warm, safe place where this kind of thing never happens.

Later, with our children safely decanted into their beds, I learn that her name is Daisy. Daisy, a pretty, delicate flower, had waltzed into Bink and Smithson, the architects’ practice in Holborn where Martin works, to offer after-sales service. ‘What sort of after-sales service?’ I bark at him.

I am torturing him, dragging out every sordid detail. It should feel satisfying, but it doesn’t. We sit facing each other across the cluttered kitchen table.

‘She … she works for the water-cooler company. They’d installed some coolers, and—’

‘Get to the point!’

‘She … well, she came back, just to make sure the water had reached the right temperature … asked if there’d been any problems at bottle-changeover time …’

Right. And lingered at Martin’s desk, laughing at his jokes, complimenting his choice of shirt and tie, making him feel so

good

and

young

again, and finally lunging at him – taking the defenceless kitten by such surprise that he found one hand plunging into her lacy 34C bra, and the other into her matching knickers.

‘And she, um … we um … It just happened,’ is how he puts it.

Naturally, his colleagues had gone home by this point. And I made that bit up, about her underwear matching. Water-Cooler Slapper doesn’t strike me as someone who’d permit her peachy arse to come into contact with tragic saggy pants.

So Martin’s hands had fallen into these places, in the way that Travis’s foot

fell

against Eddie Templeton’s butt during a row over a ripped painting at nursery. I hadn’t realised that crucial parts of Martin’s anatomy – hand, penis – are capable of behaving completely independently of his brain. Perhaps he needs to see a doctor about his nerve connections.

‘When did this happen?’ I ask dully.

‘Um, three months ago. About three months.’