My Dear Bessie

Authors: Chris Barker

Also by Simon Garfield

Expensive Habits

The End of Innocence

The Wrestling

The Nation's Favourite

Mauve

The Last Journey of William Huskisson

Our Hidden Lives

We Are at War

Private Battles

The Error World

Mini

Exposure

Just My Type

On the Map

To the Letter

Â

Â

Published in Great Britain in 2015 by Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street,

Edinburgh EH1 1TE

This digital edition first published in 2014 by Canongate Books

Letters copyright © Peter Barker and Irena Souroup, 2015

Introduction and selection © Simon Garfield, 2015

Afterword © Bernard Barker, 2015

Epilogue © Irena Barker, 2015

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful to be notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78211 567 0

eISBN 978 1 78211 568 7

Typeset in Minion Pro by Cluny Sheeler

Only on paper has humanity yet achieved glory, beauty, truth, knowledge, virtue, and abiding love.

George Bernard Shaw

Contents

Introduction by Simon Garfield

7: Error of Judgement Regarding Salmon

Introduction

I

n the autumn of 1943, a 29-year-old former postal clerk from north London named Chris Barker found himself at a loose end on the Libyan coast. He had joined the army the year before, and was now serving in the Royal Corps of Signals near Tobruk. He saw little action: after morning parade and a few chores he usually settled down to a game of chess, or whist, or one of the regular films shipped in from England. His biggest worries were rats, fleas and flies; the war mostly seemed to be happening elsewhere.

Barker was self-educated, a bookish sort. He fancied himself as the best debater in his unit, and he wrote a lot of letters. He wrote to his family and former Post Office colleagues, and an old family friend called Deb. He wrote about the local food and customs, and the occasional trip away from camp with his brother Bert. On Sunday, 5 September 1943, he found a spare hour to write to a woman named Bessie Moore. Bessie had also been a Post Office counter clerk, and was now working in the Foreign Office as a Morse code interpreter. They had once attended a training course together at Abbey Wood in south-east London, a time she

recalled with greater fondness and precision than he did. Before the war they had written to each other about politics and union matters, and about their ambitions and hopes for the future. But it had always been a platonic relationship; Bessie was stepping out with a man called Nick, and Chris's first letter to Bessie from Libya regarded them as an established couple. Bessie's reply, which took her several weeks to compose and almost two months to arrive, would change their lives forever.

We do not have this letter, but we may judge it to be unexpectedly enthusiastic. By their third exchange, it was clear to both of them they had ignited a fervour that would not easily be extinguished. In under a year, the couple were planning marriage. But there were complications, such as not actually seeing each other, or remembering quite what the other looked like. And then there were other obstacles: bombs, enemy capture, illness, comical misunderstandings, disapproval from friends, fear of the censor.

More than 500 of their letters survive, and this book distils the most alluring, compelling and heart-warming. It is a remarkable correspondence, not least because it captures an indefatigable love story. There is no holding back, and the modern reader is swept along in a gushing sea of yearning, lust, fear, regret and relentlessly candid emotion. Perhaps only those with steel hearts will fail to acknowledge an element of their own romantic past in this passionate tide. But there is so much more to enjoy, some of it banal, much of it humorous (that is, humorous to us, while evidently vital to them), all of it composed with a deft and elegant touch.

The vast majority of these letters are from Chris; most of Bessie's were burnt by Chris to save space in his kitbag and conceal their intimacy from prying eyes. But she is present on almost every

page, Chris responding to her most recent observations as if they were talking in adjacent rooms. We follow their transactions with the eagerness of a soap opera fan; the main villain is the war itself, closely followed by those they berate for keeping them apart. The erratic nature of the postal service as Chris moves from North Africa to hotspots in Greece and Italy is another bugbear, though it is also a constant wonder that the letters got through at all. We fear for both of them; the greater their joy, the more we anticipate disaster.

Chris and Bessie met only twice between his first letter in September 1943 and his demobilisation in May 1946, and their postal romance describes a fitful and compacted arc. Older readers may recall the advertising campaign for Fry's chocolate bars, a treat Chris particularly enjoyed. In the adverts, five boys are each depicted with a different facial trait: Desperation, Pacification, Expectation, Acclamation, Realisation. We get a similar range in this correspondence, not always in that order, often within a single letter. We pass swiftly from overwhelming physical compulsion to domestic furnishings. But we detect no hint of irony from the writers: they just let rip. Many of their letters were several pages long, and contained fleeting and dutiful observations of little interest to us today. There is also much repetition, not least of their romantic yearnings. Occasionally, Chris embarks on extended philosophical discussions of trade unionism, family politics and the state of the world in general. In my attempt to present a progressive and engaging narrative, I have chosen to retain only the most relevant, substantial and engrossing details. Accordingly, many letters from Chris have not been included at all, while others have been trimmed to a few paragraphs.

Who were these two people? What occupied their thoughts before each other? Horace Christopher Barker (or Holl to his parents) was born on 12 January 1914, and the austerity of the period never left him. His father, a professional soldier, spent the Great War in India and Mesopotamia, and later became a postman (with a sideline in emptying public phone boxes of their coins). Chris was brought up first in Holloway, north London, and then four miles away in Tottenham. When he left Drayton Park school at the untimely age of fourteen his headmaster's leaving report noted the departure of âa thoroughly reliable boy, honest and truthful, and a splendid worker. His conduct throughout was excellent: he was one of the school prefects and carried out his duties well. He was very intelligent.'

His father had lined up a job for him in the Post Office, confident of a secure, if predictable, lifelong career. Chris began as an indoor messenger boy in the money order department, fared well at the PO training school, and found a position as a counter clerk in the Eastern Division. His passions were journalism and trade unionism, and he combined them in his regular columns in several Post Office weeklies. He was a pedantic, reliable, headstrong man. Not the life of the party, perhaps, but a solid fellow to have in your corner. He was certainly no Casanova.

The Barker family moved to a semi-detached âvilla' in Bromley, Kent, shortly before the outbreak of war, and Chris lived there until 1942. His training as a teleprinter operator ensured his status in a reserved occupation before the demand for army reinforcements brought him first to a training camp in Yorkshire in 1942, and then to North Africa.

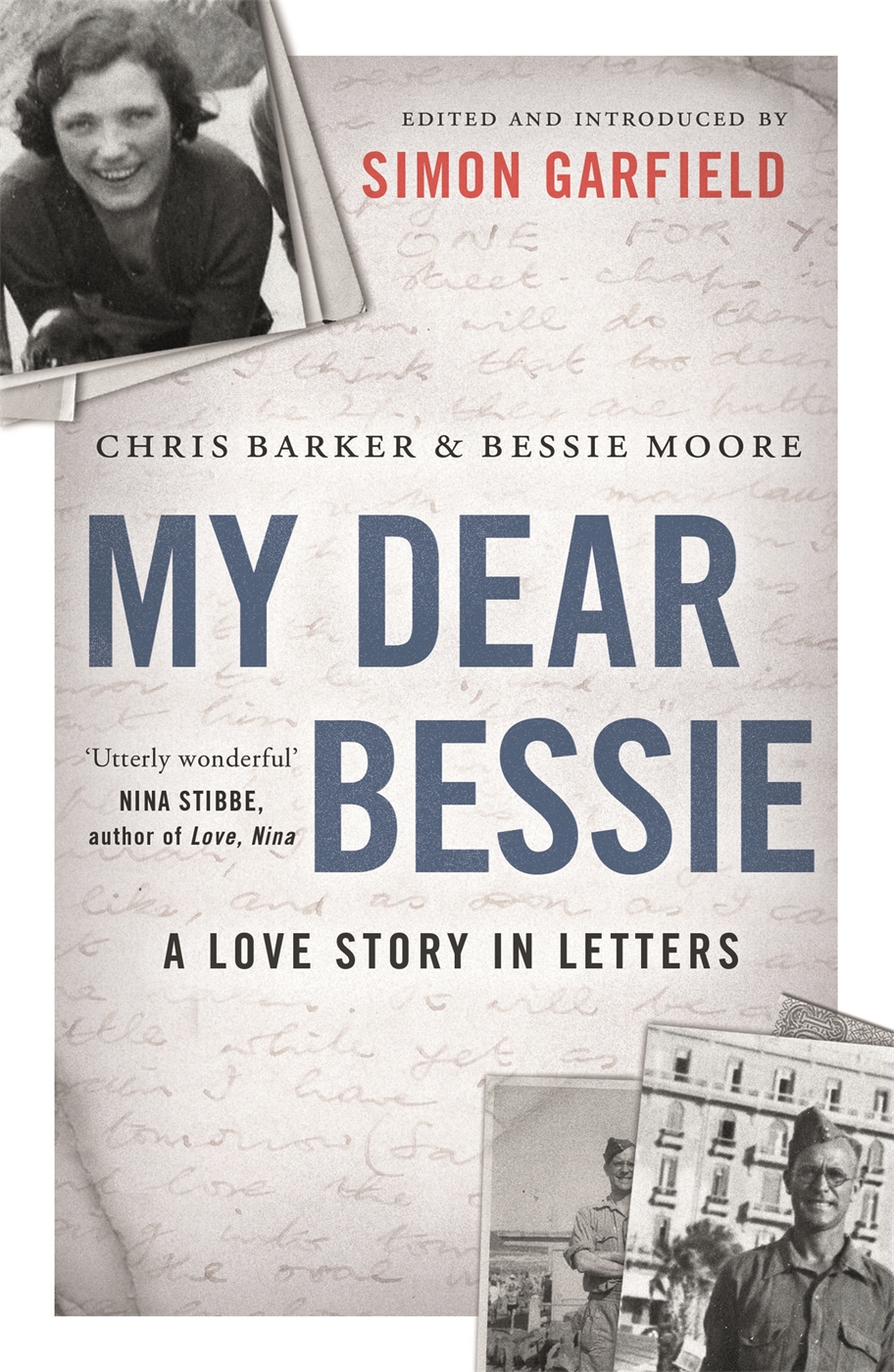

Bessie Irene Moore (known as Rene or Renee to her family and some friends) was born on 26 October 1913, two years after her brother Wilfred, and she spent her early years in Peckham Rye, south London. She had two other siblings, neither of whom survived infancy. Her father, also called Wilfred, was another âlifer' at the Post Office. Bessie won a scholarship to her secondary school, passed her exams with credit, and became a postal and telegraph officer in the female-only offices in the South Eastern, Western and West Central districts. She shared Chris's view that there could be no more worthwhile employment, filled with human incident and variety, and dedicated to public service.

Bessie was twenty-five when she moved with her family to Blackheath in 1938. The Moores enjoyed a relatively prosperous lifestyle, taking regular holidays to the seaside and frequent trips to West End theatre. Bessie particularly admired the work of George Bernard Shaw and Kipling, and developed an interest in gardening and handicrafts. Shortly after the outbreak of war, her training in Morse led to a job at the Foreign Office deciphering intercepted German radio messages. She endured the Blitz and engaged in fire-watching duties, and volunteered for the Women's Auxiliary Air Force until her mother died in 1942 and she began looking after her father. When her relationship with her boyfriend Nick broke up in 1943 she believed she had wasted far too much energy in the pursuit of love.

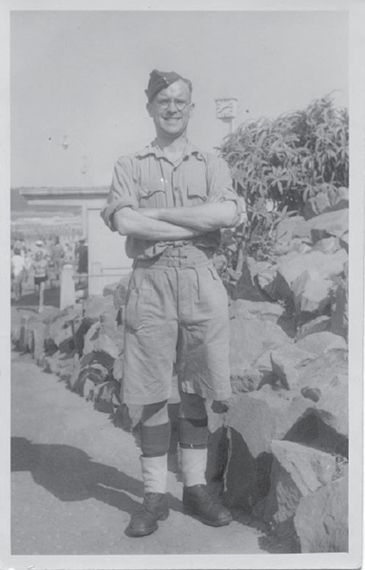

Chris Barker in Libya, 1944

I first came across Chris and Bessie's letters in April 2013. I was completing my book

To the Letter

, a eulogy to the vanishing art of letter-writing, and I was becoming increasingly aware that what my book lacked was, unpredictably, letters. More specifically, it lacked letters written by people who weren't famous. I had been concentrating on Pliny the Younger, Jane Austen, Ted Hughes, Elvis Presley and the Queen Mother, and I had been talking to archivists about how historians will soon struggle to document our lives from texts and tweets. It became clear that what the book needed was a significant example of the ability of letters to transform ordinary lives.