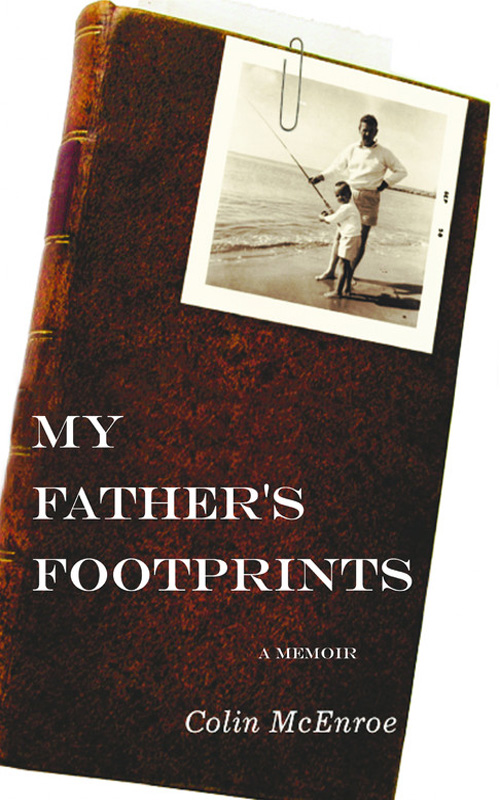

My Father's Footprints

Read My Father's Footprints Online

Authors: Colin McEnroe

Copyright © 2003 by Colin McEnroe

All rights reserved.

“Telemachus’ Detachment from

Meadowlands

by Louise Glück. Copyright © 1996 by Louise Glück. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

Material from “Faerieland” by Colin McEnroe in

Northeast Magazine,

June 21, 1992. Copyright

The Hartford Courant

. Reprinted with permission.

“Let’s Wait” by Pablo Neruda, copyright 1992. Reprinted by permission of Grove Atlantic.

“I Wouldn’t Bet One Penny,” published by Warner Chappell, copyright 1961 by Johnny Burke; copyright renewed 1989 by Mary Kramer,

Rory Burke, Timolin Burke Goldfarb, and Reagan Drew. Reprinted by permission.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: December 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56637-7

My friend, colleague, and in-law Steve Metcalf used to play the organ in a gospel church, and when it came time for members

to stand and give personal testimony, a certain woman would rise and mention—among the many blessings afforded her by heaven—“My

friends all know me.”

The meaning of this is obscure and, in another way, obvious. It’s sort of the ultimate acknowledgment. If my friends all know

me, what else do I need to say?

(My secret fear is that I will acknowledge people who were barely aware of this project and whose absentminded “hmmmph”s and

“mmmmmmm”s I over-embraced as encouragement. And now they see their names here and think: I was one of his pillars? He must

be desperate.)

This project took shape mainly with the help of my old colleagues at the

Hartford Courant,

led by Kyrie O’Connor and

Lary Bloom, and with the support of

Men’s Health

magazine, where Peter Moore and his crew took a chance on an essay that became chapter one of this book. The Books for a

Better Life people honored that essay and drew the attention of Warner Books. Many thanks to the endlessly patient Karen Melnyk

and her successor, Katharine Rapkin.

Esther Newberg is my agent. So watch out.

I thank also my colleagues at WTIC for putting up with my absences and states of distraction. I had friends who helped in

ways immeasurable and measurable. These include Peter and Sally Shapiro, Bill Curry, Denise Merrill, Jessie Stratton, Frank

Rich, and Bill Heald. Susan Campbell did not hit me (even) once during the writing of this book.

Epic gratitude to Luanne Rice, all-knowing, all-seeing, all-giving, and Anne Batterson, who rescued me and my book from all

kinds of mistakes.

Thanks to the good people of Mountnugent, especially those mentioned in chapter five, and to Susan McKeown, for the inspiring

music of “Lowlands.”

Some of the names in this book were changed, but I’m not saying which ones.

Thanks to all of you who believed in my father’s work, during his life and afterward. Thanks to all the family members who

supported me, especially my wife, Thona, and son, Joey. For rights to use Joey’s image in “My Father’s Footprints—The Video

Game,” you need to negotiate directly with his people.

And thanks most of all to my mother, who could have vetoed the whole idea and didn’t.

Contents

2. Why Nobody Understands Turbulence

5. Straight Outta Roscommon or Why History Can Be So Hortful

6. In Which the Court Adjourns

When I was a child looking

at my parents’ lives, you know

what I thought? I thought

heartbreaking. Now I think

heartbreaking, but also

insane. Also

very funny.

“T

ELEMACHUS

’ D

ETACHMENT

”

BY

L

OUISE

G

LÜCK

On the most beautiful evening of the spring of 2002, we ride our bikes, Joey and I, and somehow wind up at the grave.

Joey is twelve now, four years older, very different, and yet exactly the same as the boy you will meet in this book. Embedded

in the earth is a small granite slab into which his grandfather’s name has been cut. He doesn’t like to see me step onto it.

“Don’t stand on it!”

“Why not? Bob’s not here. He’s not underneath this stone.”

Joey climbs up on a reddish-brown boulder next to the grave. My mother and I picked the site partly because of the boulder.

“Where is he?”

“Maybe in the air around us.”

In the pine trees behind the boulder, someone has hung chimes, and they ding softly in the breeze.

“Is that it? Is he in the air around us? Or is it: When you die, you die?” Joey demands.

“Some people think that.”

“Is that what you think?”

“I think it’s possible that we become something greater.”

“What does that mean?”

“Well,” I fumble, “when we’re in these bodies… we suffer from sorrow, need, guilt, hunger, pain, fear…”

“Dad, that’s

your

life,” he interrupts, and I laugh. He laughs, too.

“What I was going to say,” I resume at last, “is that maybe when we die, we become something more pure and more joined-together

with everything else. Maybe we move beyond those limitations of sorrow and pain.”

“Maybe we’re born into another body,” Joey says. “Maybe it’s like one of my video games. You have to get to Level Ten before

you get out.”

We fall silent, and only the chimes speak.

“This is movie-like, with the ringing,” he says at last. He gestures in a way that takes in the whole scene and, I think,

the conversation. “It’s like a movie.”

I look at him, and love, dark and fiery, rips through me. He has thickened with preadolescent chunkiness. Wriggling into his

Latino identity, he has been hanging with the Puerto Rican kids at school, cribbing their fashions. He wears chains and robin’s

egg–blue Carolina football shirts and bulky dark denim shorts that droop to the knee. He is a long way from the little boy

who darted like a beach bird across the early days of this story. I will love him with every drop of my lifeblood no matter

who he is.

We get our bikes and ride home swiftly. I want to write it all down before it changes in my head. And I do, scribbling it

verbatim onto a series of five Post-Its, the first pieces of paper I find.

But first there’s the bike ride out of the cemetery with the sun low in the west, like a hole in the sky-side, letting the

gold stream in, across the trees, heavy with spring flowers, across the stern white slabs of the dead.

Emerson said heaven walks among us, so maybe my father is here, gleaming in all that slanting golden afternoon light.

Seal Barks and Whale Songs

Sarah Whitman Hooker Pies recommended with this chapter

Mother Teresa’s Mouse Pie for religious cats, bats, and owls

Mother Teresa’s Mouse Pie for religious cats, bats, and owls

Westinghouse Six-Stroke Air Pie with jelly beans and old subway tokens

Westinghouse Six-Stroke Air Pie with jelly beans and old subway tokens

The Green Bastard

The Green Bastard

T

he last time my father died was in 1998. It differed from his other deaths in that, this time, we buried him. The McEnroes

were, until recently, the sort of Irish-American family that favored florid Irish wakes. I remember my parents returning from

one of the last good ones, around 1970. They were pretty well lit, and my mother explained that one of the McEnroes, a

man in the liquor business as it happened, parked a station wagon loaded with potables in the funeral home parking lot. The

mourners would filter out there, have a nip, and return to the parlor, their enthusiasm for the wake and their nostalgia for

the dead vastly refreshed.

Their bodies heavy with weeping and their minds sodden with drink, they eventually managed to lock the keys inside the station

wagon. Very quickly, it came to pass that getting the station wagon unlocked was the thing of paramount importance, so that

virtually everyone who had been inside the funeral home was now out in the parking lot giving advice and jiggling coat hangers.

The poor corpse was left alone with one or two sniffling women.

My father was faintly amused, but it was, he said, a puny affair compared to the wakes of distant summers.

“Then,” he said, “the women would keen, making such an awful high-pitched racket you thought you were going to lose your mind.

And when the men were drunk enough, they’d haul the body out of the casket and prop it up in a chair, put a drink in one hand

and a cigarette in the other.”

He paused and smiled, letting his hazel eyes wander up in the air to where the memories floated like dust motes.

“The whole idea,” he said, a little dreamily, “was to make sure the son of a bitch was really dead.”

The last time my father died, the son of a bitch really was.