My Guantanamo Diary (31 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

“Can you take me to America with you so that I can have an operation

on my neck?” he asked.

I thought it was a joke. “What? You want to go to America?” I

asked, not believing that he would ever want to go to the United

States after his experience. “Why not England, France, or Germany?”

There was silence as all heads turned toward us. But the old

man really wanted to go to the United States, despite everything.

“Why not? I never had disliked America or Americans. I never

considered them my enemy, and I didn’t do anything to them,” he

said, opening up one of his tirades. “It was my own Afghans who betrayed

me. Not the Americans. The Americans were foolish to believe

lies and not to investigate, but they came to Afghanistan not knowing

anything or who they could trust. My real enemy was some dishonorable

lying Afghan who probably sold me to the Americans.”

Abdul Wahid joined in. “We have never been against the Americans.

We support the current government. I work with the new

democracy,” he said. “My father would like to go to America for

medical treatment, that’s all.” He explained that his father’s paralysis

could be cured with surgery. They had taken him to Islamabad,

Pakistan, many years before for an operation, but it had been unsuccessful,

and the surgeons said that the old man needed to go to Europe

or America for treatment.

Nusrat showed me the surgical scars on the back of his neck.

“

Bachai

, if you can help me get a visa, maybe I will be able to

walk again,” he said. “But I need permission to be a guest in America

to get the treatment first.”

I told him that it might be difficult for him to get a U.S. visa because

his classification as an enemy combatant hadn’t been rescinded

upon his release. If there was any possibility of getting a visa for the

purposes of seeking medical treatment, he would need some medical

documentation from his doctors stating that treatment for his paralysis

was not available in Afghanistan. I told him I’d look into it when I

got home. He seemed happy with that and encouraged me to eat more.

“Why are you eating like a bird? You need to gain some weight,”

he said.

A few hours later, I was ready to head back to Kabul, but the family

insisted that I stay for dinner, spend the night, and leave in the

morning. Nusrat said he wanted me to spend a few months with

him. I said everything I could think of to convince them to let me go,

promising that I’d stay longer the next time I visited, but after some

back-and-forth, Haji finally relented. “Next time you come, you

spend at least one month with my family,” he said. “If I find out you

ever came to Afghanistan and didn’t visit, I will be upset with you.”

I assured him I wouldn’t do that.

Before I left, I took some pictures to take back to Izatullah at

Gitmo.

“Make sure you tell him you saw me with your own eyes. Tell him

there is no difficulty and by the grace of the Almighty, he will be

among us very soon,” Nusrat said.

As I collected my things, he added, “Allah has made you a great

woman. You should marry a great Afghan man.”

“You think so?”

“Yes, I do. Marry a man of your

wathan

.”

I didn’t want to tell Haji that my fiancé was a white-bread American

from California. I knew he wouldn’t understand. Somewhere

along the way, I’d reached a level of equilibrium in my cultural balancing

act. I no longer struggled with the classic East versus West

identity crisis; I wanted to be accepted as a viable product of both

worlds. I handpicked the characteristics that suited me from both

cultures and left out the ones I didn’t care for. But I knew that others

wouldn’t always understand, and if I’d told Nusrat about my fiancé,

I think I would have eroded my own sense of peace with where

I now found myself.

At the same time, I felt, at some level, as though I was deceiving

him. It was the same way I felt at Guantánamo. I’d never told any of

the prisoners that I was engaged to an American man, someone with

no roots in Afghanistan, or any Middle Eastern country for that

matter. I knew that they all expected me to be a good Pashtun girl

who played by their centuries-old rules. I’d tried to tell the truth

once, when my client Hamidullah al-Razak kept plying me with personal

questions. I tried to dodge them initially, but part of building a

relationship and trust with your clients is engaging them not just on

a legal level but on a personal one as well. So, I finally relented and

told him about my fiancé. I was happily surprised when he accepted

it easily, and I felt better about not having lied to him. But on the following

trip, I was met by a cross-armed, stern-faced Mohammad Zahir,

a fifty-four-year-old Ghazni schoolteacher, who wasn’t thrilled

by the rumor he’d heard, and I had to backtrack on my story. I felt

badly about lying, but Gitmo is such a delicate and intense environment

that I felt it was wisest.

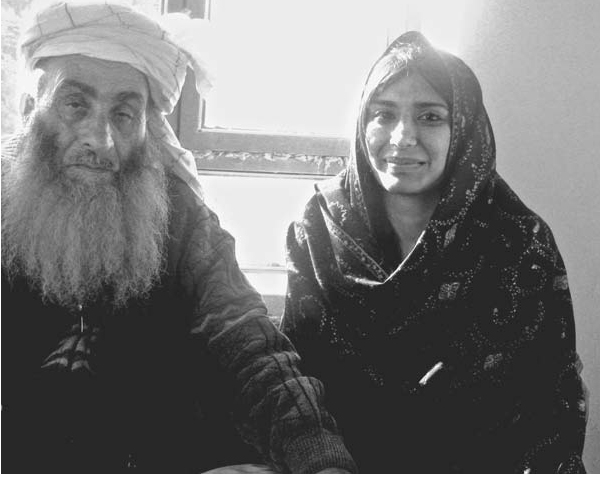

Haji and I.

Photo by Abdul Wahid.

But I really cared about Haji Nusrat. I knew that he had been tortured,

humiliated, beaten, and imprisoned without charge for many

years, that he’d been through so much at the hands of Americans.

And yet, I didn’t have it in me to try to reason with him and explain

my position.

I knelt back down and told him he looked better than I’d imagined.

I was happy to see him free, and I prayed that his son would

join him in Afghanistan soon too. He took my hands in both of his

and gave them a squeeze.

“You’re a good daughter. You kept your promise,

bachai

,” he said.

“Today, you made me happy. God is great, and God is merciful.”

“Take good care of yourself, and I’ll see you and Izatullah next

time I am here, inshallah” I replied.

On the night of October 9, 2006, guards informed four men in Camp

3, Block 1 that they would be sent home on the night of October 11.

Goatherd Taj Mohammad was one of them. He was ecstatic. The

night before his flight, he could hardly contain himself. He could

barely speak and prayed nonstop, asking everyone in adjacent cells

to pray as well that the news was true.

The next night, guards accompanied by Red Cross workers came

to fetch the men. They were all given white uniforms and white shoes

for the flight home and transfer of custody in Afghanistan. I suppose

it would make for a bad photo op if the U.S. military released “noncompliant”

detainees in tan and orange prison garb. Once the men

were dressed and ready, the guards unlocked their cages one by one,

as other prisoners looked wistfully on.

When I met with Abdullah Wazir Zadran on the morning after

Taj’s departure, he said the place would be very quiet without him.

Zadran was happy for his

friend, but I sensed a twinge of

envy too. The two had become

close while imprisoned together.

Taj stays in touch with Abdul

Salam Zaeef in Kabul and asked

Zaeef to pass on his contact information

to me. I tried calling

him, but we ended up playing

phone tag; he travels an awful lot

for a goatherd and is often not in

town. When he was, I had a

friend of mine go to his village

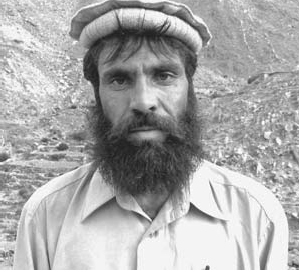

and take a picture of him nine months after his release. He also wrote

me to say that he’d like a copy of this book—in Pashto and in English.

Taj Mohammad in Kunar after his release.

Photo courtesy of Nimatullah Karyab.

When I do get hold of him, I plan to find out whether he’s still interested in taking a second wife, from America.

The families of Salah al-Aslami and the two Saudi prisoners who

the U.S. military said committed suicide at Gitmo on June 10, 2006,

continue to mourn their deaths. Al-Aslami’s young widow, Hayat

Warshad Ali, still hasn’t recovered and remains bedridden in the

family home.

The U.S. military has never conducted a conclusive investigation.

To date, the Department of Defense (DOD) has also refused

to release the suicide letters that were supposedly written before the

men hanged themselves. The DOD has also continued to turn down

requests for anatomical samples of the organs removed from the

victims’ bodies.