My Life So Far (61 page)

Among the members of the cast of

Julia

was a newcomer playing the role of the bitchy black-haired Anne Marie. I remember the first time I saw rushes in which she appeared; it was the scene where Lillian comes into Sardi’s restaurant following the smash opening of her Broadway play

The Little Foxes.

I am seen making my way through the crowd of well-wishers, and as I walk offscreen the camera lingers on Anne Marie’s face: With a slight hand gesture to her mouth and an indefinable look in her eyes, the young actress revealed an entire character. I think my own hand must have come to my mouth at that moment, and as soon as rushes were over I ran to a phone to call Bruce in California. “Bruce,” I said, quite out of breath, “listen carefully. There’s this young actress with a really strange name, Meryl Streep. Yes, M-e-r-y-l, with a ‘y.’ I haven’t seen an actress so amazing since Geraldine Page. I’m telling you, she’s going to become a huge star. We have to try right away to get her for the other woman’s part in

Coming Home.

” As it turned out, Meryl was committed to a play and unavailable. But I feel lucky to have had that early glimpse of her unique talent.

Another wonderful thing about

Julia

was the chance to work again with Jason Robards. We had done a silly comedy back in the sixties,

Any Wednesday.

But in

Julia

he was perfect as Lillian’s gruff, leave-no-prisoners partner, Dashiell Hammett, author of

The Thin Man.

Tom brought Troy to Europe twice, for ten days each, during the three-and-a-half-month shoot. Years later he told me how hard these long separations were for him. I accepted the fact that he had to remain in California to take care of organizational matters. I didn’t want to face the possibility that he was angry—or that

I

was angry that he and Troy didn’t visit more.

Before leaving, I had hired a baby-sitter to help Tom out. She was a nice, attractive young woman; I thought she was sexy and told Tom so. One night in Paris during his visit, he told me he wanted to talk to me about something; it was about the baby-sitter, he said. He reminded me that I thought she was sexy, and from the way he then hesitated, I sensed what was coming and told him not to say any more. “I don’t want to hear it,” I said. I assumed he was going to tell me he had slept with her. I was going to have to be by myself for another month once he was gone, and I didn’t want to be angry and do something I would regret. Since we didn’t even talk about far easier subjects, it should be no surprise that we never discussed the issue of monogamy or what I expected from him when I was away for so long. Because I hadn’t worked a lot during our first years together, it took him by surprise when I began to be absent for work. I’d done

A Doll’s House

in Norway and then another film in Leningrad,

Blue Bird,

directed by George Cukor, and now

Julia.

This was new for him. It was usually Tom who did the coming and going. Perhaps he was used to having a more “open relationship” with other women, but my experience with Vadim had taught me that it didn’t work, at least not for me. I take full responsibility for cutting Tom off from what might have been an important conversation for the good of our relationship. But neither one of us ever broached the subject of infidelity again. I never did find out what, if anything, had happened between Tom and the baby-sitter.

Vanessa was now seven years old. I told Vadim I didn’t think it was good for her to keep breaking up her school year between California and Paris. At least partially because of this, when he and Catherine Schneider divorced, Vadim moved to his old haunt on Malibu Beach and remained in California for a good part of the next five years, later moving into a house in Ocean Park a few minutes from us.

Three years had elapsed since we had begun work on

Coming Home,

but the script still wasn’t quite ready when

Julia

wrapped. By now, at the instigation of Jerry Hellman and to our great good fortune, Hal Ashby had come on board as our director. Hal, an offbeat, aging hippie of a man, with glasses, long wispy gray hair, and a full beard, had directed some of my favorite films:

Harold and Maude, The Last Detail,

and

Shampoo.

He appeared to be very laid-back but in reality was wired and tough as a bull. When Waldo Salt had the heart attack, Hal brought in his longtime friend, editor and screenwriter Robert Jones, to complete the script. Working overtime and selflessly, Jones crafted a script from Waldo’s first draft and many notes, but the script remained a work in progress during the entire shooting. Haskell Wexler, who had filmed

Introduction to the Enemy

with Tom and me in North Vietnam and

Bound for Glory

with Hal, was our cinematographer. Jon Voight had been offered the role of my husband, the rigid marine officer, but he worked tirelessly to convince us all that he was the man to play Luke, the paraplegic role inspired by Ron Kovic. Jon participated actively in much of the research with the vets, and finally his passion and commitment persuaded us to go with him. Bruce Dern, my old pal from

They Shoot Horses

days, would end up being wonderful as my husband.

Multitasking during a lunch break on

Fun with Dick and Jane—

fund-raising for Tom’s U.S. Senate campaign.

(Michael Dobo/www.dobophoto.com)

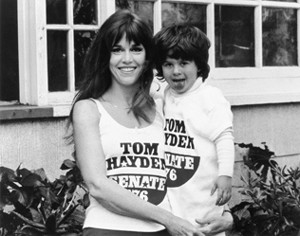

Me and Troy in our campaign T-shirts.

(Star Black)

Campaigning with Tom.

(Anne Marie Staas)

While Jones was working on the script, out of the blue I got a script from my friend Max Palevsky and his producing partner, Peter Bart, called

Fun with Dick and Jane.

It was serendipity—a social satire about an overconsuming, middle-class, keep-up-with-the-Joneses couple (Dick was played by George Segal) and how they deal with his sudden layoff from an executive position at an aerospace company. Despite all the trappings of the American dream (mainly for the neighbors’ benefit), they own nothing and have saved nothing. All they have are mortgages and credit card debts. As soon as word of his firing gets out, all the creditors show up to repossess everything. Faced with the hard realities of people on food stamps and welfare, they turn to crime. I couldn’t believe my luck—a quick shoot that didn’t require me to leave home, in a comedy with something to say, in which I could show I was still funny and could still look good. The film would be released before

Julia

and be my “she’s back” film, proving to the studio heads that I was still a bankable star.

Fun with Dick and Jane

was an easy film from an acting point of view, which was fortunate because I spent every second I wasn’t on camera raising money for Tom’s Senate race. I organized an auction that brought together Steve Allen, Jayne Meadows, Groucho Marx, Lucille Ball, Red Buttons, Danny Kaye, and my dad in support of Tom. I got Linda Ronstadt, Jackson Browne, Arlo Guthrie, Bonnie Raitt, Maria Muldaur, the Doobie Brothers, Little Feat, Chicago, Boz Scaggs, Taj Mahal, James Taylor, and many others to do benefits; I got Dad to do paintings I could auction off (I bought them all myself). I was a whirlwind of activity on Tom’s behalf, and when

Fun with Dick and Jane

was finished, I traveled the state, building support and putting hundreds of thousands of dollars into the campaign war chest. In the end he didn’t win, but he got 36.8 percent of the vote—1.2 million Californians had cast their votes for a New Left radical, cofounder of SDS, and co-conspirator of Chicago. This was unprecedented in recent political history.

But we lost. I think I took it harder than Tom did. I felt it as

my

failure—not an unusual response, I have discovered, for women whose sense of self is tied to their husbands’ public life. Does this surprise you? Me, with my financial independence and career? But there you have it. A woman can be powerful professionally, socially, and financially, but it is what goes on behind the closed doors of her most intimate relationship and within her own heart that tells the story. And like Vadim, Tom defined me to myself: If brilliant, articulate Tom was with me, then I couldn’t be all bad.

Tom kept his promise to César Chávez and morphed his Senate campaign structure into a statewide grassroots organization called the Campaign for Economic Democracy (CED), which focused on economic issues. The average American family was earning less then than a decade earlier; inflation, largely the result of the Vietnam War, was robbing them of their savings; and unemployment was rising sharply as more corporations automated or took jobs overseas to cheap labor markets. We also took on the nation’s reliance on foreign oil and the use of nuclear energy (we pushed the use of alternative energy sources like solar and wind); we supported small farmers against agribusiness; and we fought for the rights of workers, including office workers. Many of CED’s concerns found their way into the movies I would subsequently make.

A

s soon as

Dick and Jane

wrapped, we began shooting

Coming Home,

even though many of the key scenes still weren’t locked in. In fact, we had no ending everyone was happy with, and Hal and I disagreed about the nature of the critical love scene between Luke and my character, Sally Hyde. There were always vets in wheelchairs all around us as we filmed, and a few had their girlfriends with them. Some were quadriplegic, which means the injury is high up on the spine and paralysis is from the neck down; some were paraplegic, which means the wound is lower on the spine and paralysis is from the waist down (for a man, the lower down the wound, the less the penis is affected). I remember one quadriplegic in particular, whose really cute girlfriend would sort of flip him over, fold him up, and sit on him playfully. There was a vibe about them that was utterly trusting and deeply sexual. Since I needed to find out as much as I could about what sex was like for a couple in their situation, I talked to them quite a bit. I learned that the girl had been brutalized by a previous boyfriend who had once thrown her from a moving train. This in itself was illuminating: It made sense that a victim of abuse would be attracted to a man who couldn’t hurt her physically. When it came to sex they said they never knew when he would have an erection; it was not connected to anything she did or said. “It can happen anytime—when we’re driving past a gas station or looking at a daisy. But when it happens it can last for hours . . . one time for four hours,” she said with a sexy, knowing look to him. I had to go off by myself and think about that for a while till my palms stopped sweating.

Anyway, until the dramatic “four hour” revelation, genital penetration was not something I had considered possible between my character and Jon’s, and this to me was a powerful aspect of the story—a dramatic way to redefine manhood beyond the traditional, goal-oriented reliance on the phallus to a new shared intimacy and pleasure my character had never experienced with her husband. But Hal didn’t see it that way. He too knew the “four-hour story,” and penetration was definitely where he was headed with the scene.