My Sergei (8 page)

Authors: Ekaterina Gordeeva,E. M. Swift

My father’s attitude started to change after we finished second in the Skate Canada competition because we weren’t well prepared.

Also, Zhuk had driven me to tears in August when I wanted to go to our dacha one weekend to pick mushrooms with my grandfather.

We had no training time scheduled. Zhuk said, “Fine, Katia, but first come over and we’ll listen to some music for a new program.

It will only take a couple of hours and then you can go.” So I went, and it took all day, and we didn’t have time to go to

the dacha. He upset me so much, and when I saw my father I couldn’t hold in my tears. Which was when my father finally said,

That’s enough.

It was an awkward situation for the entire Central Red Army Club, since Zhuk carried the rank of a colonel. Armies the world

over like to protect their own. The generals who oversaw CSKA finally decided that Zhuk could keep his title as head coach,

but that Stanislav Viktorovich Leonovich would coach us, and travel with us, and otherwise be completely in charge.

Leonovich had won a silver medal in pairs at the 1982 Europeans with his partner, Marina Pestova. For one year we had trained

on the same ice together at CSKA, and I had always called him Stas. Now that he was our coach, I began calling him by his

first two names—Stanislav Viktorovich—which is more formal and respectful. He was a nice man, a kind man, with an interesting

face. He had a cute nose, almost like a duck’s nose, and it made me want to smile just to look at him. Although Sergei and

I were so happy to be rid of Zhuk, my father worried that Leonovich wasn’t tough enough to be our coach. He didn’t think he

had enough experience.

But under Leonovich, everything changed, and skating became enjoyable again. The first thing he did was to bring back Marina

as our choreographer, and she resurrected the Duke Ellington number that she’d made for us in 1985, the one that Zhuk had

not let us skate because it was too difficult. It became our free program that year.

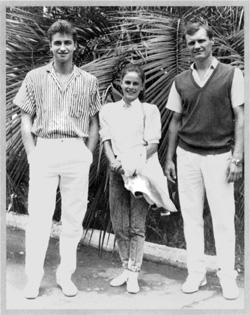

With our new coach, Stanislav Viktorovich Leonovich.

This number had more dancing, more footwork, more choreography, and more fun than anything we’d skated to before. Marina,

Leonovich, Sergei, and I used to be the envy of all the other skaters because we had such a good rapport on the ice, always

laughing and enjoying ourselves. When Sergei missed a practice, as he still sometimes did, Leonovich never raised his voice.

Instead of getting angry, he would say, “Do you understand that because of your absence, Marina, Katerina, and I weren’t able

to work yesterday?” Leonovich always called me Katerina—he was the only one to do so—because he thought it would make

me feel older. He’d say, “There is more than just you, Sergei, who’s involved.” And Sergei understood this reasoning, and

he stopped missing the practices. Rather, he stopped missing them alone, because as we grew older, he sometimes taught me

to skip a practice with him so we might go fishing or waterskiing together on the Volga River. He never forgot there was more

to life than the ice.

We won the Nationals for the first time that season, then went to the 1987 European Championships in Sarajevo. That summer

we had learned a very difficult move called the quadruple split twist, in which Sergei threw me in the air, I did a split,

then closed my legs and made four turns before he caught me. We were the only pair to do this quadruple element, and it was

very exhausting—more exhausting than difficult, really. Soviet doctors had measured my pulse rate as exceeding two hundred

beats per minute when I did it. I had to spin so fast that one time my elbow caught Sergei in the eyebrow, and within a few

seconds his eye had swelled closed, and the next day it was a grisly black and blue.

Sergei turned twenty on the day we skated the long program at the Europeans, which we would long remember because of an unfortunate

occurrence. In the first minute we had successfully done the quadruple split twist, which even Scott Hamilton, who was doing

television commentary, incorrectly identified as a triple. So did most of the judges, which is one of the reasons we dropped

this element from our program before the Calgary Olympics: it expended so much energy but didn’t appreciably improve our marks.

Then somehow the elastic strap at the bottom of Sergei’s pants broke.

This strap was flapping around Sergei’s ankle. It wasn’t a danger, because it had snapped back up and was not dragging on

the ice. But the referee, Ben Wright, an American, started blowing his whistle because he was worried that Sergei would trip.

We heard the whistle, but we didn’t know that it meant for us to stop. And with the triple salchow throw coming up, I was

much more concerned about that. When I landed it perfectly, all the most difficult elements were behind us, and we naturally

wanted to continue. Zhuk had always said to keep skating no matter what is happening around you, and only listen to your coach.

Then Ben Wright had the technicians turn off our music. It was eerie, to be skating in a full arena to complete silence. We

looked over to Leonovich, but he made no sign for us to stop. “Skating?” I asked Sergei. “Yes, we’re skating,” he said quickly.

So without our music playing, we continued our program, which was very tiring because of the concentration required. We had

never, ever practiced our program this way. But we were skating well, no mistakes, and the audience began clapping for us

long before we had finished. Afterward we were exhausted and very confused.

The judges were instructed not to write down our marks. The Russian judge told Leonovich that we could skate the program over

again after two more pairs had skated, giving us a short time to rest. But neither Sergei nor I wanted to do this. We didn’t

think we could skate any better than we just had, and we didn’t understand that if we didn’t skate again, we’d be disqualified.

So when, after two more pairs, Leonovich asked if we were ready, we told him no. We were all done. He should have pushed us

more, but Leonovich was never pushy. Sergei just didn’t want to skate it again, and neither did I. We were disqualified from

the Europeans.

This was a sign of Leonovich’s inexperience. First, he should have told us to stop skating when the whistle blew. Then, he

should have insisted that we try again, no matter how tired we were, knowing that the judges would surely mark the defending

World Champions leniently after such an unfortunate incident. But it was a mistake the three of us shared responsibility for,

and it made us angry as we prepared for the 1987 World Championships in Cincinnati.

Ben Wright was at the Worlds, too, and he apologized to us for what had happened. We said that we, too, were sorry and did

not hold him to blame. In Cincinnati we skated our free program, this time to music, as well as we were able. In fact, of

all our competitions, the 1987 Worlds may have been the time when we skated our best. We successfully defended our title,

and this time, when it was over, I had no impulse to cry.

Afterward we went on our first American tour with promoter Tom Collins, a nice man who puts on a show every year that features

exhibitions by the World and Olympic champions. He has an exclusive arrangement with the ISU, and the skaters—who in those

years were all amateurs—love to be invited on his tour, which plays to packed arenas throughout North America. According

to ISU rules, we were only allowed, I think, eight hundred Swiss francs a year in cash payments, but Tom always gave us extra

money, maybe fifty to a hundred dollars a week. We weren’t supposed to talk about it. But it was enough for me to be able

to buy a four-hundred-dollar TV for my parents before I went home. Sergei helped me pick it out at a store in New York that

was owned by a Russian sailor. He also helped me choose a suitcase in which I could carry all the clothes that I bought for

my sister and me, and all the gifts for my parents and grandparents. Russian skaters always had huge luggage problems on the

flight home.

My English at the time was almost nonexistent. I had taken English in school but had missed many classes because of skating,

and I didn’t even remember the alphabet. Sergei and I would go into a restaurant, open a menu, and have no idea what anything

was. It made me self-conscious all the time.

My roommate on that tour was Tracy Wilson, the Canadian ice dancer, whose partner was Rob McCall. She was older than me, and

I think Tom Collins wanted her to watch out for me. She ordered room service every morning and always asked if I wanted something

too. If I said yes, she never let me pay for it, no matter how hard I tried.

During this tour, I always sat with Sergei on the bus. He read quite a lot, while I looked out the window or did needlepoint.

It was new for me to spend time with him off the ice. He would sometimes come to my room and ask me to go for a walk, or to

go with him for dinner. We didn’t have much money, so it was just to McDonald’s or maybe a pizza place. Sasha Fadeev was also

on this tour, but Sergei still went with me.

Maybe he was just taking care of me. I didn’t know. He always helped me with my luggage and offered me a hand when I was stepping

off the bus. But this was just the way he was. He also offered his hand to the next lady stepping off the bus. He was a gentleman,

and I think maybe he learned this from watching Leonovich, who was the same way. Leonovich had always treated his partner,

Marina Pestova, with respect. He believed that how partners got along with each other was as important as how they looked

in practice. If everything was all right off the ice, everything would be all right on the ice, too. Leonovich, I think, was

too kind to be a coach.

When we were in Los Angeles, Sergei and I went to Disneyland with Sergei Ponomarenko and Marina Klimova, who were married.

It was just the four of us, and Sergei was very happy that day, in such a good mood, always laughing and being funny. He bought

me some ice cream. A couple of times he hugged me after a ride, or put his arm around me when we were standing in line. He

had never done this before, and it made me excited. This was a wonderful day for me.

The tour went to twenty-five cities and lasted a month. So many new experiences. In New York Tom Collins got us tickets for

Phantom of the Opera,

and beforehand we ate dinner at Sardi’s, which had all the pictures of celebrities on the wall. Another time Sergei and I

danced together at a place with a jukebox, but not just the two of us. There were four or five of us dancing in a group. Sometimes,

after we had skated and were waiting to go out for the finale, Sergei would hug me in the hallway, but never if someone was

watching.

I didn’t think much about these little attentions. At least I don’t remember reading too much into them. A couple of times

Sergei and I went to the movies, and we held hands during the show. I don’t know why that was such a big deal, since we held

hands all the time on the ice. But this was different. This was nice. I remember how hard my heart was beating when he reached

over and took my hand. Afterward I didn’t say anything. I just smiled at him. I never asked why he was holding my hand. All

I knew was that it felt great.

I figured it was only because he was excited to be on this tour and was feeling so good that he did it. I didn’t think it

had anything to do with me. I assumed when we returned to Moscow, he’d go back to being the same way he’d been before.

Yet things changed after that tour. My mother, who adored Sergei, began to invite him to the house all the time. She loved

how he played with our Great Dane, Veld. It was now easier for me to give him things, and even flirt with him a little bit

if he was in the mood for it. It wasn’t like I was planning anything or had any great designs to capture his affections. Sergei

and I never planned anything, ever, more than two days ahead of time. Especially about our relationship.

American women, I think, plan much more than Russian women. At least the Russian women who grew up in the seventies and eighties,

before the breakup of the Soviet Union. American women have much more to plan for. Not only must they try to find a life partner

who’s a doctor or lawyer or businessman, but he must be good looking, too.

In Russia, everyone was more or less on the same level. There was very little difference between being rich and poor. So if

you found someone you liked, or loved, the next question was only when the marriage would be. Not whether he could make a

good life for you or was a suitable match for you. There was no need for elaborate planning. Today, of course, it is different,

and Russian women know how to look for a good businessman with money to marry the same as Americans do. But I never had such

notions in my head.

F

or training purposes, it was now an Olympic year. I was

sixteen, Sergei was twenty; and everything became focused on that single goal.

Our preparations began in June 1987, when we went to Sukhumi in Soviet Georgia for twenty days, which is where Marina started

to create two new Olympic programs for us. Our support staff was larger than it had ever been. We had a special conditioning

coach to oversee our running and lifting. We had a team of doctors who checked our weight every day and tested our blood several

times a week by pricking our fingers. Heaven knows what they were looking for. We ate better food. The figure skating federation

gave us caviar every day, which was high in protein and low in fat.