My Story (25 page)

Authors: Elizabeth J. Hauser

“If you were really a game man I would suggest a line of action,” I answered, “but I don't think you would carry it out, so there's no use in my advising you.”

This appealed to his vanity and he begged me to advise him. He said he would do anything I suggested except go to jail, and he'd even do that if I would promise

to protect him. I therefore advised him to keep his appointment with Dr. Daykin and take whatever money was offered to him. In less than two hours he came back with two thousand dollars.

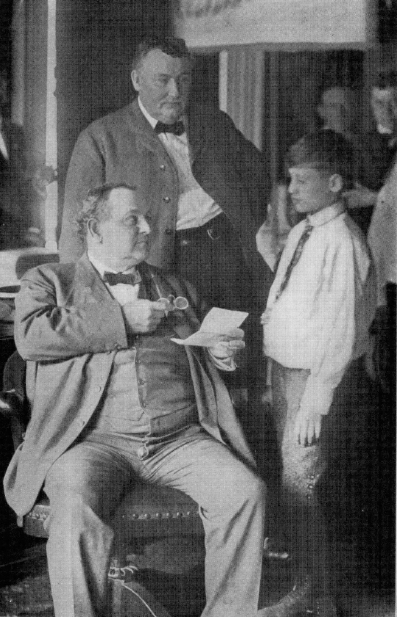

MR. JOHNSON IN 1905

That night a dramatic scene occurred in the council chamber. I was speaking, Dr. Daykin was among the spectators sitting outside the railing. I charged that attempts had been made to bribe some of the councilmen in order to prevent the passage of the ordinance. The charge created a sensation, for bribery wasn't taken lightly in that body, or in that community. The councilmen and the lobby were giving the closest attention to what I was saying. The interest was intense. At a certain point in my speech and by pre-arrangement with Kohl he threw the two thousand dollars on the table before me, and no other proof of my charges was necessary. In the excitement Dr. Daykin hurried for the door, but I was watching him and called out, “You won't get very far, Doctor. Some of my friends are waiting for you outside.” The ordinance passed without a dissenting vote. Whether it would have been possible to carry it without this incident I do not know.

Dr. Daykin was arrested and after a long trial in which many persons testified he was acquitted. We thought he was acting for a combination of coal dealers and the artificial gas people, but did not know positively, and weren't able to prove it.

The reason I wanted the franchise passed to the Standard Oil people was that I was eager to get for the people of Cleveland cleaner and cheaper fuel and light than the coal companies or the artificial gas people could furnish them. I believed the Standard Oil people had a monopoly

of the natural gas field â there was no one else from whom to buy â the city could not compete with them.

Whatever the fault of the Standard monopoly it wasn't due to Cleveland or to Ohio; neither the city nor the State was responsible for it. At bottom it was a land monopoly. Our friends the Socialists hold that such monopolies should be taken over by the government and operated for the benefit of the people. I contend that they can be taxed out of existence. It really doesn't make a great deal of difference, so far as I can see, however, whether the community owns and operates a monopoly, or whether it takes in taxes the value to which it is rightfully entitled. That the people should get the benefit is the important thing â the method is secondary.

One of our liveliest fights â the one on which the final success of our municipal lighting plant was based â has already been alluded to along with the activity of the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company and its success in preventing the repassage of the ordinance by council and the special bond issue election. In the fall of 1903 we lost the bond issues which were submitted, along with everything else, so our municipal lighting project was still a thing of the future. In the 1904 election the citizens of Cleveland voted eight to one and those of the village of South Brooklyn three to one in favor of annexing South Brooklyn to the city. The city council appointed City Solicitor Newton D. Baker, Frederic C. Howe and James P. Madigan, annexation commissioners. Now South Brooklyn owned a small electric lighting plant and for this reason Privilege was opposed to annexation. To have Cleveland acquire a municipal lighting

plant in this way was as obnoxious to the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company as the city's other plan had been, and its fight was now directed against annexation. The first move was to have council reconsider its action on the appointment of the annexation commission and appoint another friendly to the lighting company. I refused to confirm the appointment of this second commission and publicly charged fifteen Republican council-men with misfeasance and two Democrats with bribery. A councilmanic investigation was started. The city solicitor ordered the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company to open its books for examination by council. The company got out a temporary injunction restraining the city from enforcing this demand, which order was made permanent a few days later by Judge Beacom, whom I had appointed director of law at the beginning of my first administration. The city carried the case to the circuit court, which sustained the decision of the lower court, and so the investigation was effectually blocked. I made the unfriendly councilmen very angry by maintaining that the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company seemed to have more power than forty thousand voters, but it was true that the expressed will of the people in the 1904 election had to wait more than a year before it could be put into effect. Before the next election I went into the wards of the two Democratic councilmen, above referred to, and defeated their re-nomination.

After the pronounced victory in the 1905 election, when we carried twenty-five of the twenty-six wards of the city, the councilmen got together and voted to accept the report of the annexation commissioners, which provided for

the immediate annexation of South Brooklyn. The councils of both city and village passed the necessary ordinances, December 11, 1905.

Under the law, annexation would not be complete until a record was filed with the county recorder and a copy forwarded to the Secretary of State. The work involved in preparing these papers prevented the completion of the annexation until the Thursday following the Monday night council meeting, but in the meantime, on Tuesday morning, the mayor and the solicitor of the village of South Brooklyn called at the City Hall, and told Peter Witt, the city clerk, that an ordinance granting a renewal of street car rights on certain streets to the Cleveland Electric Street Railway Company had had two readings and that they feared it might be given a third reading and passed, thereby further entangling the street car situation. Without consulting anybody Witt called up Chief Kohler and asked for an officer. His request was at once complied with and he hustled one of his deputies and the policeman off in a municipal automobile with instructions to bring back the town clerk and all the records of the village of South Brooklyn. The automobile got back to the City Hall about noon with the cargo it had gone after. The village clerk turned over all the records, but Witt was taking no chances and at his request three policemen were detailed to watch the town hall in South Brooklyn, the village policemen (three in number) were also given instructions to keep a sharp lookout and to break up any attempt to hold a council meeting. No such attempt was made and by Thursday annexation was finally accomplished, and Cleveland was in possession of a small municipal lighting plant.

The city later acquired another such plant in the annexation of Collinwood.

When Newburg was in process of being annexed to Cleveland a twenty-five-year franchise to the Cleveland Electric Street Railway Company was hurried through the village council, the signature of the mayor only being required to complete the ordinance. The newspapers all said that the mayor had announced that he would sign it, and that was the general expectation. The last meeting of the village council was held the last night that the village had legal existence as such, and it certainly looked as if our problems were to be complicated by a village grant to the street railway company. But at the last moment the mayor vetoed the ordinance. The newspapers said that the first intimation anybody had that he was not going to sign was when he called up his wife that night and told her he had changed his mind. Our whole movement seemed to be constantly beset with incidents fraught with the greatest possibilities of defeat or success. There was something doing all the time.

It was early in my third term that Chief Kohler found it necessary to take drastic steps to stamp out an effort to revive public gambling. In a rapidly growing city with a numerically inadequate police force, it is almost impossible to keep this vice within bounds. Kohler did it, though, but he did not hesitate to employ heroic measures on occasion. He seized the gambling paraphernalia from a hotel and smashed it with an ax, destroying two mahogany tables, cards, markers and chips. After his third raid on this hotel the chief appealed to John D. Rockefeller as owner of the property to cooperate with him in his efforts to stop gambling there. Kohler has a way of

holding the owners of property responsible for the uses to which it is put instead of placing all the blame upon the tenants, which is sometimes very disconcerting to big landlords.

At the very time when gamblers were inveighing against the administration on one hand, the ministerial association of the city was complaining about it on the other. Personal representatives of both called upon me. The gamblers admitted that I had “played no favorites,” but had treated them all alike, and the ministers gave me credit for not making promises and then breaking them. I really took some pains to explain to these last named gentlemen that I was quite as much interested in the welfare of society as they were, but that I was trying to reach the root cause of the conditions of which they complained, whereas they seemed to be concerned with symptoms only.

But whatever the other matters that engaged our attention they were small compared to the street railroad question which was always up. It was this that engaged most of our time, used up our energy and taxed our ingenuity. The chief reason why this was such a big question was that it involved the largest financial problem, for the receipts from the street railroad were about equal to the receipts of the city government from all sources.

PERSONAL LIABILITY SUIT AND THE “PRESS”

GUARANTEE

T

HE

summer of 1906 found the street railway fight raging fiercely. It was constantly growing in intensity and bitterness and in personal animosity towards me. This animosity culminated in the fall of 1906 in an effort to connect me personally with the three-cent-fare street railroad grants. The old company contended in one breath that these grants had no value, and in the next that my relationship to them was so close that it constituted a personal pecuniary interest. This personal liability question grew out of an injunction to prevent the low-fare people from operating cars on Concon tracks for about six hundred feet on Detroit avenue,â which tracks had been for years considered free to joint occupancy of any company with the consent of the city.

The Concon proposed to show personal financial interest in the low-fare company on my part, thereby proving invalid the grant signed by me as mayor. A summary of the low-fare movement from its inception to this time will help the reader to understand the absurdity of this foolish charge.

The aim of the low-fare propaganda was municipal ownership which the laws of Ohio did not permit, but we were getting ready for it in making the fight for better service and lower fares, thus teaching the people that they had some jurisdiction in the regulation of public service

utilities. Our entire Cleveland fight in one sense was a struggle to have recognized the sacredness of public property by private interests as the sacredness of private property is recognized by public interests. We never attacked private property. We were always engaged in the struggle to force the recognition of the rights of public property, whether in public hands or private hands. We never advocated the breaking of a contract, no matter how unfair that contract was to the people, but constantly resisted the claims and quibbles of ingenious lawyers to extend over public property private rights that did not exist.

In spite of the tremendous pressure brought against it by the public service corporations, through unfair newspapers, constant litigation, and political tricks of various kinds, the low-fare movement made its way. The organization of a new traction company known as the Forest City Railway Company was secured and grants were made to this company with the provision that they could be acquired by the city at not more than ten per cent. above cost, as soon as a municipal ownership law could be obtained. The Forest City line was obstructed every time it made a move, as has already been repeatedly shown. It costs money to build and equip railroads, but the expense is enormous when you add to it the cost of litigation growing out of a new injunction suit nearly every day. It was not easy to capitalize an enterprise which was so badly handicapped, and to find a person too honest to be bought, willing to take the risk of losing money without any possibility of making more than an ordinary six or seven per cent. investment was one of the most difficult tasks I had to face during the whole of the low-fare

fight. But the man for just this emergency came to us in the person of my friend, ex-Congressman Ben T. Cable of Rock Island, Illinois. Mr. Cable put one hundred thousand dollars into the company and later an additional two or three hundred thousand. At any time when the fight was warm he could have sold out to the old company at an immense profit, and not only defeated the low-fare movement but brought discredit upon all connected with it. He fulfilled every obligation and his service to our cause cannot be over-estimated. I didn't see then and I don't see now how we could have prevented a disastrous defeat without Mr. Cable's timely assistance.

The opposition newspapers meanly insinuated that he must have some ulterior motive and delighted in calling him my “cousin,” as if to prove thereby that he could not aid the low-fare fight in a disinterested way. When the final history of that struggle shall be written Mr. Cable's service will surely be given the high place that it deserves.

In 1905 the city proposed to the old company a settlement of the whole vexed problem by means of the organization of a holding company. It was my idea that this holding company should take over all the street railway interests of the city as lessee. A fair rental should be paid and the property operated in the interests of the public and not for profit. As security to the old company a twenty year franchise should be granted to the holding company with the agreement that it should revert to the private interests if the holding company failed to make good under the terms of the lease. The city offered to place a valuation of eighty-five dollars a share on the Concon stock, which figure was much too high, for the

price offered would have given the old company about three times as much for their property and unexpired franchises as it would have cost to rebuild the whole system in first class condition. The advantages that would accrue to the city it is impossible to measure in money, as it would remove the biggest incentive for bad government by Big Business. This offer they rejected and in 1908 they were forced to accept a settlement based on a price of fifty-five dollars a share.

The Municipal Traction Company was then organized as the holding company and completed in the summer of 1906 with A. B. du Pont as president and director, Charles W. Stage, Frederic C. Howe, Edward Wiebenson and William Greif as the other directors, and W. B. Colver as secretary. The directors were salaried and self-perpetuating, but neither they nor the company were to profit in any other way. Their books were open to the public and all their transactions were public. The holding company owned no railroad, but became the lessee of the Forest City Company. The capital for construction was raised by the sale of Forest City stock at ninety cents on the dollar and deposited in trust for use in construction by the holding company. The holding company agreed to construct and operate the low-fare lines, to pay six per cent. on the capital, to pay off the capital at ten per cent. above par and to devote the entire surplus to extensions and improvements. Everything had been done openly. There had been no secret negotiations with the old company nor in other directions.

Both the Cleveland Electric and the Forest City were seeking franchises. As the Cleveland Electric was known as the Concon, so the Forest City and the other low-fare

companies organized later were called the Threefer. Here is a parallel comparison of their offers to the city for such franchises:

Photo by L. Van Oeyen

Asking the Mayor's permission to play ball on streets

| CONCON. | THREEFER. |

| CASH FARES . | |

Five cents. | Three cents. |

| TICKET FARES . | |

Seven for twenty-five cents; | Three cents. |

| TRANSFERS . | |

Limited as at present to lines to be built. | Universal under constant council regulation. |

| FRANCHISES . | |

Irrevocable grants. Bargain to be made now for twenty-five years. | Revocable grants. Franchise to be terminated at any time. |

| SERVICE . | |

Promises with no reserved right to council to enforce. | Full power left to council to regulate at any time under penalty of revoking franchises. |

| EXTENSIONS . | |

Promised, but at discretion of the company; profit on unlimited capitalization. | Promised and discretion left in the city; profit on actual cost only. |

| SUBWAYS AND ELEVATEDS . | |

Subways or elevateds some time, if a rate of fare can be agreed upon. | Subways and elevateds whenever council directs, and at a 3-cent fare. |

| CAPITALIZATION . | |

$150,000 per mile. | $50,000 per mile. |

| DIVIDENDS AND PROFITS . | |

All that can be gotten on $150,000 per mile. | Only six per cent. on actual money investment within $50,000 per mile. |

| CITY OWNERSHIP . | |

Prevented for at least twenty-five years. | Always possible if desired by the people and permitted by the Legislature. |

| TITLE TO THE STREETS . | |

Prevented for at least twenty-five years. | Remains absolutely In the city for all time. |

| PUBLICITY . | |

Books closed to the council, city and public. | Books kept open to all who may care to look. |

| POPULAR VOTE . | |

One vote to be binding for twenty-five years. | Submission to the people at any time. |

| FINALITY OF SETTLEMENT . | |

Makes a repetition of the present struggle continuous and inevitable. | Ends the struggle for eliminating private interests from this public service. |

| GROWTH IN NET EARNINGS . | |

All benefits reserved to the stockholders of the company. | All benefits reserved to the people of the city of Cleveland. |

Early in the summer council ordered the Concon to move its tracks on Fulton road from the center of the street to one side to make room for the tracks of the Forest City, which company had a franchise to lay tracks on the west side of the street. Having had so much previous experience with the old company's disregard of orders from council the city was authorized to remove the tracks at the Concon's expense, provided the latter had not complied with the order at the end of the thirty-day period stipulated therein. No attention whatever was paid to the city's order; it wasn't even acknowledged. The thirty days elapsed, then two weeks more; then, early on the morning of July 25 a big force of workmen under the direction of the mayor and Server Springborn proceeded to rip up the tracks. Every preparation for getting the work done quickly and in the best possible way, and with the least damage to the pavement, had been made in advance. The ends of the track were torn up first so that the cars of the Concon could not block the work. This move on the part of the city was a complete surprise and found the old company quite unprepared. It was about eleven o'clock a. m. (and the work had been going on since seven) before the injunctions were served on the mayor and Mr. Springborn. These injunctions were so ambiguously worded, due no doubt to haste and to the court's lack of information regarding the real facts in the matter that it was anything but clear what they proposed to restrain. It was too late anyway to restrain us from removing the tracks that were already up. Our “lawlessness” occasioned a great howl among the real law-breakers and Mr. Springborn and I were charged with contempt of court. The contempt proceedings occupied

about a week and at the end of that time, on August 3, I was exonerated, but Mr. Springborn â certainly the least culpable of any person connected with the transaction from first to last â was found guilty. He was fined one hundred dollars, which, I am happy to say, he never paid.

The Forest City Company, which had proceeded with the laying of its tracks on the west side of the street, was enjoined July 26 and the work had to stop while the matter was fought out in the courts. Eventually it was able to proceed once more. In the city's case we were also successful, the court holding that the city had acted within its rights and was under no obligation to replace the old company's tracks.

The track which the city tore up was, by a curious coincidence, on the very street the bidding on which had been the occasion of my coming to Cleveland twenty-seven years before. It was on this street in 1879 that I had been beaten by Simms and Hanna, and it was over this street too that a three-cent car was to run a few months later.

or 3.57.

or 3.57.