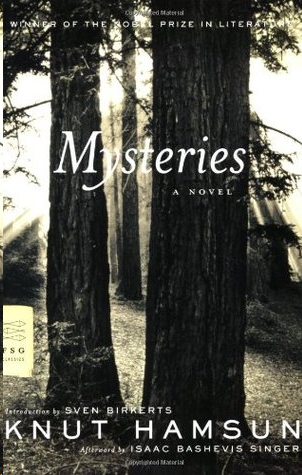

Mysteries

Authors: Knut Hamsun

Table of Contents

MYSTERIES

Knut Hamsun was born in 1859 to a poor peasant family in central Norway. His early literary ambition was thwarted by having to eke out a living—as a schoolmaster, sheriff’s assistant, and road laborer in Norway; as a store clerk, farmhand, and streetcar conductor in the American Midwest, where he lived for two extended periods between 1882 and 1888. Based on his own experiences as a struggling writer, Hamsun’s first novel,

Sult

(1890; tr.

Hunger,

1899), was an immediate critical success. While also a poet and playwright, Hamsun made his mark on European literature as a novelist. Finding the contemporary novel plot-ridden, psychologically unsophisticated and didactic, he aimed to transform it so as to accommodate contingency and the irrational, the nuances of conscious and subconscious life as well as the vagaries of human behavior. Hamsun’s innovative aesthetic is exemplified in his successive novels of the decade:

Mysteries

(1892),

Pan

(1894), and

Victoria

(1898). Perhaps his best-known work is

The Growth of the Soil

(1917), which earned him the Nobel Prize in 1920. After the Second World War, as a result of his openly expressed Nazi sympathies during the German occupation of Norway, Hamsun forfeited his considerable fortune to the state. He died in poverty in 1952.

Sult

(1890; tr.

Hunger,

1899), was an immediate critical success. While also a poet and playwright, Hamsun made his mark on European literature as a novelist. Finding the contemporary novel plot-ridden, psychologically unsophisticated and didactic, he aimed to transform it so as to accommodate contingency and the irrational, the nuances of conscious and subconscious life as well as the vagaries of human behavior. Hamsun’s innovative aesthetic is exemplified in his successive novels of the decade:

Mysteries

(1892),

Pan

(1894), and

Victoria

(1898). Perhaps his best-known work is

The Growth of the Soil

(1917), which earned him the Nobel Prize in 1920. After the Second World War, as a result of his openly expressed Nazi sympathies during the German occupation of Norway, Hamsun forfeited his considerable fortune to the state. He died in poverty in 1952.

Sverre Lyngstad, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of English and Comparative Literature at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey, holds degrees in English from the University of Oslo, the University of Washington, Seattle, and New York University. He is the author of many books and articles in the field of Scandinavian literature, including

Jonas Lie

(1977) and

Sigurd Hoel’s Fiction

(1984), coauthor of

Ivan Goncharov

(1971), and cotranslator of Tolstoy’s

Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth

(1968). Among his more recent translations from Norwegian are Knut Fadbakken’s

Adam’s Diary

(1988), Sigurd Hoel’s

The Troll Circle

(1992) and

The Road to the World’s End

(1995), Knut Hamsun’s

Rosa

(1997) and

On Overgrown Paths

(1999), and Arne Garborg’s

Weary Men

(1999). Dr. Lyngstad is the recipient of several grants, prizes, and awards and has been honored by the King of Norway with the St. Olav Medal and with the Knight’s Cross, First Class, of the Royal Norwegian Order of Merit. He has recently completed a critical study of Knut Hamsun’s novels.

Jonas Lie

(1977) and

Sigurd Hoel’s Fiction

(1984), coauthor of

Ivan Goncharov

(1971), and cotranslator of Tolstoy’s

Childhood, Boyhood, and Youth

(1968). Among his more recent translations from Norwegian are Knut Fadbakken’s

Adam’s Diary

(1988), Sigurd Hoel’s

The Troll Circle

(1992) and

The Road to the World’s End

(1995), Knut Hamsun’s

Rosa

(1997) and

On Overgrown Paths

(1999), and Arne Garborg’s

Weary Men

(1999). Dr. Lyngstad is the recipient of several grants, prizes, and awards and has been honored by the King of Norway with the St. Olav Medal and with the Knight’s Cross, First Class, of the Royal Norwegian Order of Merit. He has recently completed a critical study of Knut Hamsun’s novels.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi- 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

First published in Penguin Books 2001

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi- 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue,

Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Originally published in Norwegian as

Mysterier

by P. G. Philipsens Forlag, Kobenhavn, 1892.

Mysterier

by P. G. Philipsens Forlag, Kobenhavn, 1892.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Hamsun, Knut, 1859—1952.

[Mysterier. English]

Mysteries / Knut Hamsun ; translated with an introduction and

explanatory and textual notes by Sverre Lyngstad.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

Hamsun, Knut, 1859—1952.

[Mysterier. English]

Mysteries / Knut Hamsun ; translated with an introduction and

explanatory and textual notes by Sverre Lyngstad.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN : 978-1-440-67363-4

I. Lyngstad, Sverre. II. Title

PT8950.H3M913 2001

839.8’236—dc21

00-040651

PT8950.H3M913 2001

839.8’236—dc21

00-040651

For Karin and Ken

—

S. L.

—

S. L.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I wish to thank the following persons for information concerning special usages, literary allusions, and biographical items in translating

Mysteries

and preparing the notes: Arnold and Kjellrun Lyngstad, Michael Rijssenbeek, Guy Rosa, and Dagfinn Worren. Special thanks go to Eléonore Zimmermann for her patience and encouragement during the period I was working on the translation and for reading the manuscript.

Mysteries

and preparing the notes: Arnold and Kjellrun Lyngstad, Michael Rijssenbeek, Guy Rosa, and Dagfinn Worren. Special thanks go to Eléonore Zimmermann for her patience and encouragement during the period I was working on the translation and for reading the manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

At the time when Knut Hamsun was working on the novel that became

Mysteries,

he was also deeply, and busily, engaged in a critical crusade against the state of Norwegian literature. Already in 1890, the year his first novel,

Hunger,

appeared, he had published an essay in the journal

Samtiden

(The Contemporary) entitled “Fra det ubevidste Sjæleliv” (From the Unconscious Life of the Mind), in which he championed a new literary psychology, focused on the intangible, elusive aspects of consciousness, the very stream of thought, rather than its outcome or end results. Concurrently, he emphasized the unpredictable nature of the process of thought and its roots in the subconscious mind.

Mysteries,

he was also deeply, and busily, engaged in a critical crusade against the state of Norwegian literature. Already in 1890, the year his first novel,

Hunger,

appeared, he had published an essay in the journal

Samtiden

(The Contemporary) entitled “Fra det ubevidste Sjæleliv” (From the Unconscious Life of the Mind), in which he championed a new literary psychology, focused on the intangible, elusive aspects of consciousness, the very stream of thought, rather than its outcome or end results. Concurrently, he emphasized the unpredictable nature of the process of thought and its roots in the subconscious mind.

In 1891 he extended his crusade by going on a lecture tour of Norwegian cities, ending up in Kristiania (now Oslo) in October of that year. In these lectures, the contents of which were only known through newspaper reports until 1960, Hamsun repeated his call for a new literature while attacking the reigning deities on the Norwegian Parnassus, Ibsen, Bjørnson, Kielland, and Lie, the so-called Four Greats. Ibsen had received a special invitation to the Kristiania lecture and sat in the front row, beside Nina and Edvard Grieg. The lectures caused a sensation, but the reviews were mixed. Many critics found the attacks to be outrageously unfair as well as churlish and cast Hamsun as a Yankee self-booster, a reference to his recent sojourns in the United States.

This largely hostile public reaction is an essential part of the background to

Mysteries,

which appeared in 1892. As the reader will soon discover, the debate is continued on a wider scale in the novel. During the period of the novel’s genesis, Hamsun’s life was no less unsettled than that of Johan Nilsen Nagel, the book’s central character, as he kept moving between Kristiania and Copenhagen, between Copenhagen and the Danish island of Samsø, and from one Norwegian town to another. His finances were also precarious: the sales of

Hunger

were poor despite excellent reviews. These circumstances were bound to have a strong impact on the book he was writing. Indeed, in creating the central figure of

Mysteries,

Hamsun produced an aggravated or heightened version of his own provisional life: Nagel, whose rootlessness is global, represents the extreme limit of an existential condition with which his creator was intimately familiar. In effect, he can be seen as a virtual self of the author, whose artistic vocation helped prevent its real-life actualization.

1

Mysteries,

which appeared in 1892. As the reader will soon discover, the debate is continued on a wider scale in the novel. During the period of the novel’s genesis, Hamsun’s life was no less unsettled than that of Johan Nilsen Nagel, the book’s central character, as he kept moving between Kristiania and Copenhagen, between Copenhagen and the Danish island of Samsø, and from one Norwegian town to another. His finances were also precarious: the sales of

Hunger

were poor despite excellent reviews. These circumstances were bound to have a strong impact on the book he was writing. Indeed, in creating the central figure of

Mysteries,

Hamsun produced an aggravated or heightened version of his own provisional life: Nagel, whose rootlessness is global, represents the extreme limit of an existential condition with which his creator was intimately familiar. In effect, he can be seen as a virtual self of the author, whose artistic vocation helped prevent its real-life actualization.

1

That vocation had not come cheaply. Hamsun’s beginnings as a writer had been slow and painful. By the time he appeared on the scene with a fragment of

Hunger

in 1888, he had served a literary apprenticeship of more than ten years and tried his fortune on two continents. His life, never an easy one, was often marked by severe hardship. Born to an impoverished peasant family at Garmotrxdet, Lom, in central Norway in 1859, Knut Pedersen, to use his baptismal name, had a difficult childhood. In the summer of 1862, when Knut was less than three years old, his father, a tailor, moved with his family to Hamarøy, north of the Arctic Circle, where he worked the farm Hamsund belonging to his brother-in-law, Hans Olsen. From the age of nine to fourteen Hamsun was a sort of indentured servant to his uncle, since the family was financially dependent on him. The boy’s beautiful penmanship made him particularly valuable to Hans Olsen, who suffered from palsy and needed a scribe for his multifarious business, from shopkeeper to librarian and postmaster. The uncle treated Knut with anything but kid gloves; at the slightest slip of the pen he would rap his knuckles with a long ruler. And on Sundays the boy was kept indoors, forced to read edifying literature to Hans and his pietist brethren while his friends were playing outside, waiting for Knut to join in their games. No wonder he liked to tend the cattle at the parsonage, where his uncle had his quarters. This allowed him to lie on his back in the woods, dreaming his time away and writing on the sky. Very likely, these hours of solitary musings away from the tyranny of his uncle acted as a stimulus to young Hamsun’s imagination. His schooling, starting at the age of nine, was sporadic, and his family had no literary culture. However, the local library at his uncle’s place may have provided a modicum of sustenance for his childish dreams.

Hunger

in 1888, he had served a literary apprenticeship of more than ten years and tried his fortune on two continents. His life, never an easy one, was often marked by severe hardship. Born to an impoverished peasant family at Garmotrxdet, Lom, in central Norway in 1859, Knut Pedersen, to use his baptismal name, had a difficult childhood. In the summer of 1862, when Knut was less than three years old, his father, a tailor, moved with his family to Hamarøy, north of the Arctic Circle, where he worked the farm Hamsund belonging to his brother-in-law, Hans Olsen. From the age of nine to fourteen Hamsun was a sort of indentured servant to his uncle, since the family was financially dependent on him. The boy’s beautiful penmanship made him particularly valuable to Hans Olsen, who suffered from palsy and needed a scribe for his multifarious business, from shopkeeper to librarian and postmaster. The uncle treated Knut with anything but kid gloves; at the slightest slip of the pen he would rap his knuckles with a long ruler. And on Sundays the boy was kept indoors, forced to read edifying literature to Hans and his pietist brethren while his friends were playing outside, waiting for Knut to join in their games. No wonder he liked to tend the cattle at the parsonage, where his uncle had his quarters. This allowed him to lie on his back in the woods, dreaming his time away and writing on the sky. Very likely, these hours of solitary musings away from the tyranny of his uncle acted as a stimulus to young Hamsun’s imagination. His schooling, starting at the age of nine, was sporadic, and his family had no literary culture. However, the local library at his uncle’s place may have provided a modicum of sustenance for his childish dreams.

During his adolescence and youth Hamsun led a virtually nomadic existence, at first in various parts of Norway, later in the United States. After being confirmed in the church of his native parish in 1873, he was a store clerk in his godfather’s business in Lom for a year, then returned north to work in the same capacity for Nikolai Walsøe, a merchant at Tranøy, not far from his parents’ place. There Hamsun seems to have fallen in love with the boss’s daughter, Laura. It is uncertain whether the young man was asked to leave because of his infatuation with Laura or because of the bankruptcy of Mr. Walsøe in 1875. In the next few years he supported himself as a peddler, shoemaker’s apprentice, schoolmaster, and sheriff’s assistant in different parts of Nordland. After the failure of his literary ventures in the late 1870s, the school of life took the form of road construction work for a year and a half (1880-81).

Hamsun’s dream of becoming a writer had been conceived at an early age, amid circumstances that left him no choice but to fend for himself. If it can be said of any writer that he was self-made or self-taught, it can certainly be said of Hamsun. Not surprisingly, the two narratives published in his teens,

Den Gådefulde

(1877; The Enigmatic One) and

Bjørger

(1878), were clumsy and insignificant. The former is an idyllic tale in the manner of magazine fiction, in a language more Danish than Norwegian. The latter, a short novel, was modeled on Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s peasant tales of the 1850s. In 1879, with the support of a prosperous Nordland businessman, E. B. K. Zahl, Hamsun wrote another novel, “Frida,” which he presented to Frederik Hegel at Gyldendal Publishers in Copenhagen. It was turned down without comment. The manuscript of this story, which was also dismissed by Bjørnson (1832-1910), has been lost. Bjørnson suggested he become an actor. And so, in early 1880, in his twenty-first year, the first period of Hamsun’s literary apprenticeship came to an end.

Den Gådefulde

(1877; The Enigmatic One) and

Bjørger

(1878), were clumsy and insignificant. The former is an idyllic tale in the manner of magazine fiction, in a language more Danish than Norwegian. The latter, a short novel, was modeled on Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson’s peasant tales of the 1850s. In 1879, with the support of a prosperous Nordland businessman, E. B. K. Zahl, Hamsun wrote another novel, “Frida,” which he presented to Frederik Hegel at Gyldendal Publishers in Copenhagen. It was turned down without comment. The manuscript of this story, which was also dismissed by Bjørnson (1832-1910), has been lost. Bjørnson suggested he become an actor. And so, in early 1880, in his twenty-first year, the first period of Hamsun’s literary apprenticeship came to an end.

During the 1880s hard physical labor went hand in hand with renewed literary and intellectual efforts. While employed in road construction, he had made his debut as a public lecturer. But though his lecture on August Strindberg was enthusiastically reviewed in the Gjøvik paper, Hamsun lost money on the venture.

2

His next decision was not unusual for a poor, ambitious Norwegian in the 1880s: to emigrate to America. However, Hamsun was not primarily interested in improving his fortune; instead, he foresaw a future for himself as the poetic voice of the Norwegian community in the New World. Needless to say, the dream quickly foundered, though the lecturing activity was continued. To support himself he worked as a farmhand and store clerk, except for the last six months or so of the two-and-a-half-year stay, when he was offered the job of “secretary and assistant minister with a salary of $500 a year” by the head of the Norwegian Unitarian community in Minneapolis, Kristofer Janson (1841-1917).

3

This was Hamsun’s first significant encounter with an intellectual milieu. While he did not share Janson’s religious beliefs, he clearly enjoyed browsing in his well-stocked library. But his stay was cut short: in the summer of 1884 his doctor diagnosed “galloping consumption,”

4

and in the fall of that year Hamsun returned to Norway, apparently resigned to die. He was twenty-five years old. His illness turned out to be a severe case of bronchitis.

2

His next decision was not unusual for a poor, ambitious Norwegian in the 1880s: to emigrate to America. However, Hamsun was not primarily interested in improving his fortune; instead, he foresaw a future for himself as the poetic voice of the Norwegian community in the New World. Needless to say, the dream quickly foundered, though the lecturing activity was continued. To support himself he worked as a farmhand and store clerk, except for the last six months or so of the two-and-a-half-year stay, when he was offered the job of “secretary and assistant minister with a salary of $500 a year” by the head of the Norwegian Unitarian community in Minneapolis, Kristofer Janson (1841-1917).

3

This was Hamsun’s first significant encounter with an intellectual milieu. While he did not share Janson’s religious beliefs, he clearly enjoyed browsing in his well-stocked library. But his stay was cut short: in the summer of 1884 his doctor diagnosed “galloping consumption,”

4

and in the fall of that year Hamsun returned to Norway, apparently resigned to die. He was twenty-five years old. His illness turned out to be a severe case of bronchitis.

Other books

Promises by Ellen March

The Tale of Oat Cake Crag by Susan Wittig Albert

Stay At Home Dead by Allen, Jeffrey

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (with bonus content) by Michael Chabon

A Mother's Wish by Macomber, Debbie

The Hunger by Marsha Forchuk Skrypuch

Long Holler Road - A Dark Southern Thriller by Malone, David Lee

Rasputin's Shadow by Raymond Khoury

Lost in Us by Layla Hagen

It's You by Tracy Tegan