Naïve Super (12 page)

We’re gonna have fun, he says.

I don’t doubt that he means well, but I think he’s going too far. He doesn’t want to hear a word about the hammer-and-peg, for instance. Not one. He’s going to break it if he finds me hammering. I’ll have to hammer on the sly. It’s humiliating. After all, I am an adult. Adults shouldn’t have to be closet-hammerers. I am trying to confront my problems in a mature way, but my brother is keeping me from it.

I think he’s got problems with time himself, but that he still hasn’t found out. One day he’ll be the one who hits the wall. When that happens I’ll let him hammer as much as he likes. Then he’ll have a guilty conscience about refusing to let me do it.

Now I think I’m seeing the Empire State Building again.

We are staying in a house where there is a doorman and an elevator attendant. And the apartment is great. But there is a dog in it. There’s a dog in the apartment. Someone called David is supposed to come and fetch the dog. He was supposed to come yesterday. I know nothing about dogs. And my brother is afraid of it. It bothers us that this dog is in the apartment. It’s a black dog. I’ve given it food and water, but I don’t know how often it’s supposed to eat. And somebody will have to walk it soon. It hasn’t been outside since yesterday, when the owners of the apartment went to New Orleans to listen to jazz or something like that. It is obvious that the dog wants to get out. It stays over by the door. My brother says I must walk it. He doesn’t dare to. I don’t even know the dog’s name.

I attach a leash to the black dog and go outside. On the way down I ask the elevator attendant if he knows anything about dogs, but he shakes his head and says there’s probably not much to know. The dog probably knows where it wants to go.

Now I’m walking on the street in New York City with a dog. It drags me a few blocks to the south, to a park. It wants to smell everything and it pees a bit here and a bit there. It pees on anything.

I’ve never quite understood about dogs. People say they’re so wise. That they have intuition and warn you about things that are about to happen. They alert you to avalanches and accidents. It could very well be true. But this dog doesn’t seem particularly bright. So far it hasn’t alerted me to anything. In the park the dog goes completely mad. It sees some other dogs and starts jumping up and down. It seems completely irrational.

I distinguish myself from the other dog owners. I don’t know what the dog expects of me. I feel everybody is looking at me. A woman comes over to me. She also has a dog. She tells me that my dog and her dog are best friends. I tell her I come from another country and that this is the first time I have walked a dog. I tell her I don’t even know what the dog’s name is.

The lady says the dog’s name is Obi and that I must be firm with it.

Easy, Obi,

I say.

I ask how often it’s supposed to eat and drink and what I’m supposed to do if it starts to crap. The lady gives me a little bag. She asks me if I didn’t get any instructions and I tell her someone called David is going to come and fetch the dog. He could be here any time now.

I speak English to Obi.

Come on,

I say.

Good dog.

Now Obi’s sitting down to take a shit. On the grass. I think it’s disgusting. Joggers and children look towards me while I pick the dog turd up with the bag. Now I’m standing with a bag full of dog turd in my hand. It’s absurd.

This is a completely different life. People must think I’m a dog owner in New York. That I live here and have an apartment and a dog. That I pick up dog turds like this one every day, before and after work. It’s a staggering thought.

Seeing as I’m not a dog owner in New York, that also means everybody else could be something other than what they seem to be. That means it’s impossible to know anything at all.

All these people. They are everywhere. On the streets, in the parks, in the shops, in the skyscrapers. What do they do? It’s impossible to tell what they do by looking at them.

I suppose they are trying to make it all come together. Just like we do in Norway and everywhere else. They try to make it all work. I see them while they’re on their way from one place to the next, torn out of their context. They’re on their way elsewhere to make things work there. Things have to work everywhere, and on many levels. It all has to work on a personal level, with the family, at work and with friends, in the local community, and of course globally.

Quite a few things have to gel.

And as I stand there with the dog, at an intersection on the east side of Manhattan, I wonder whether all this will ever gel for me. Will I make it?

I don’t think I am any different from other people. I have the same dreams. I want a family. I want a house. A car. Why shouldn’t I want that? Everybody does. And when I have it, I want it all to work.

I feel I am starting to care about all these people. I understand them. Of course they have to walk here in the street, they have to get somewhere. Things have to work everywhere. I am thinking, we’re in this together. Keep it up. It’s going to be just fine.

I keep nagging my brother to take us up the Empire State Building. He says we’re going to do it on a sunny day with clear weather. We walk and we walk. We look at houses, at people and cars. Shops. We eat and drink. I’ve bought a bunch of very small bananas. We’ve walked tens of kilometres, and I’ve got a new pair of shoes, because the old ones were giving me blisters. It was very sore. I got a pair of Nikes. Hiking boots. My brother paid for them with one of his credit cards.

I always buy Nike. And Levi’s. I think they’re the best. I really do. I don’t even consider buying other brands. Somebody must have done their job very well.

My brother is interested in art. I didn’t know that. There are many things I don’t know about him. But it’s good that we’re together. Even though he sometimes gets a little stern. We walk around in SoHo for a while. Visiting galleries. I see plans for a project that has tremendous appeal to me.

Somebody is thinking of building a massive concrete structure over the San Andreas Fault in California. It is a sculpture. It’ll be eighty metres long and sixty metres wide. And seven metres tall. It will be built with a type of concrete claimed to be the most durable material there is. The slab will weigh 65,000 tonnes. But the ground on which it’s going to stand is moving. Quite fast. The concrete slab will be torn in half, and the two parts will drift apart at a speed of 6–9 cm a year. In 43 million years the left part of the slab will be where Alaska is today. This is art with a purpose. All projects ought to be like this.

In another gallery I find a folder about Einstein. Made by an art student. She has read a lot about Einstein and found information about him and gathered it all in a folder called the Einstein Papers. I want to buy it. It costs 20 dollars. My brother thinks it’s foolish, of course. He tries to talk me out of it. But Einstein is my friend. I buy the folder. My brother is shaking his head.

Now my brother stands pointing at the Empire State Building. I can see it. It towers in the landscape. And the top floors are illuminated by a blue light. I want us to go there. Now. But my brother has made other plans. It is late. He thinks we should go home and watch TV.

We drink a beer, while a woman on TV is saying that if I have an accident, I should call her and she will help me make a court case and get money from those responsible for the accident or from those who own the ground on which the accident happened. She makes it sound so simple.

In bed, I read the Einstein Papers. It’s just twenty-odd sheets of A4 paper. Some photographs and a bit of writing here and there. Claire, who made the folder, writes that Einstein was a kind man who cared about people, and that he was very concerned that science should be a blessing to humanity. Einstein had two aspirations in life, it says. The first was to lead a simple life. The second was to formulate a theory that could express the interconnectedness of nature, and which would ultimately lead to peace and justice for all.

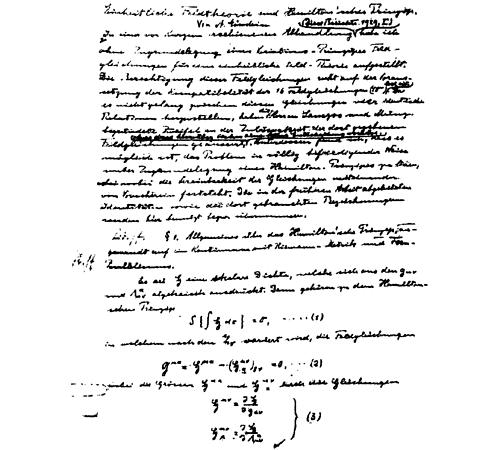

One of the sheets is a copy of one of the manuscript pages on which Einstein wrote his theory. I look respectfully at the sheet. Some words and some figures. Maybe this is where it says that time doesn’t quite exist. The sheet looks like this:

Albert Einstein, 6 1/4 page autograph manuscript of his paper,

Eincheitliche Feldtheorie und Hamilton’sches Prinzip, 1929

.

SWANN GALLERIES

The best thing in the folder is a picture of Einstein together with a group of Indians. Einstein is smiling and wearing feathers on his head. And it says that the Hopi Indians are the best suited to understand the theory of relativity. Their language does not have a word for time, and the concepts of past and future do not exist. They don’t see time as linear, but as a circular space where past, present and future exist side by side. When I get home, I want to check and see if there is a Hopi community in Oslo, and whether I can frequent it even though I’m not a Hopi.

Before I go to sleep, I write down what I remember the most from my first two days in this city:

– A man in uniform who came running out of a building to carry the luggage for an elegantly dressed woman getting out of a taxi

– Four Asian-looking boys playing volleyball on the grass in a park

– A man playing classical guitar in a subway station

– A large area cordoned off due to a burst water main

– A boy running in a park while his dad was trying to get him interested in a stick

– A shop window full of inflatable cushions

– A big man speaking Russian and frying hamburgers in a huge lump of butter

– A big bottle of beer

– A man on rollerblades who first almost crashed into a lady and who, a minute later, almost crashed into a car

– An orthodox Jew with a walkman and red trainers

– A girl giving away samples of a new brand of chewing gum, who said it was free today only

– A man sitting with a notice which said that he didn’t have any money and that he was HIV-positive

– A girl who came into a shop and asked the man behind the counter how he was doing

– A lady in sunglasses sitting in a cafe telling her friend that she’d been talking to a man until four o’clock in the morning and that it was a relationship she had faith in

– A restaurant owner standing in the street swinging a golf club while we were eating dinner

– A very long car that had tinted, black windows so nobody could look inside

– A Chinese porno magazine where the cover girl was holding a hand over her nipples

When I wake up, Obi has pulled all my little bananas off the kitchen counter. They’re all over the floor. I shake my head and say

Obi, Obi

. David still hasn’t been here. He should have come two days ago.

Someone will have to walk Obi. I have to walk Obi. I put on my new Nike shoes. Now Obi and I are going out. It’s raining.

By the entrance to the park there is a sign with a phone number you can call if you have a

Parks-related problem.

In a way, Obi is such a problem. I take down the phone number: 1-800-Parks. If David doesn’t pick Obi up by the end of the day, I’m going to call it.

A man with a dog calls from afar asking whether Obi is a he or a she. It is obvious that his dog is a she and that it is in heat. It’s running loose as well. I shout back saying that I don’t know. The man looks at me shaking his head. He thinks I’m weird.

Now I meet another man with a dog. He knows Obi, he says. He says Obi has a high metabolism, and that I should feed Obi more often than he feeds his dog. It is a meaningless piece of information. He doesn’t say anything about how often he feeds his dog. But he tells me that Obi is a he.

I have only brought one bag, so when Obi sits down to crap for a second time, he makes me embarrassed. He’s crapping on the pavement. When he is done, we cross the street and pretend nothing happened.