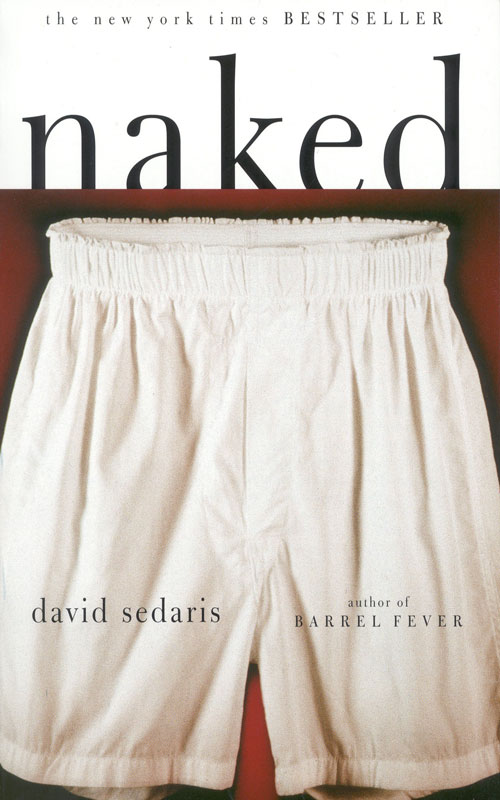

Naked

Authors: David Sedaris

Copyright © 1997 by David Sedaris

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including

information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may

quote brief passages in a review.

Back Bay Books

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: May 2009

Author’s note: The events described in these stories are real. Other than the family members, the characters have fictitious

names and identifying characteristics.

ISBN: 978-0-316-07362-2

Contents

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Holidays on Ice

Barrel Fever

For my sister Lisa

I’m thinking of asking the servants to wax my change before placing it in the Chinese tank I keep on my dresser. It’s important

to have clean money — not new, but well maintained. That’s one of the tenets of my church. It’s not mine

personally,

but the one I attend with my family: the Cathedral of the Sparkling Nature. It’s that immense Gothic building with the towers

and bells and statues of common people poised to leap from the spires. They offer tours and there’s an open house the first

Sunday of every October. You should come! Just don’t bring your camera, because the flash tends to spook the horses, which

is a terrible threat to me and my parents, seeing as the reverend insists that we occupy the first pew. He rang us up not

long ago, tipsy — he’s a tippler — saying that our faces brought him closer to God. And it’s true, we’re terribly good-looking

people. They’re using my mother’s profile on the new monorail token, and as for my father and me, the people at NASA want

to design a lunar module based on the shape of our skulls. Our cheekbones are aeronautic and the clefts of our chins can hold

up to three dozen BBs at a time. When asked, most people say that my greatest asset is my skin, which glows — it really does!

I have to tie a sock over my eyes in order to fall asleep at night. Others like my eyes or my perfect, gleaming teeth, my

thick head of hair or my imposing stature, but if you want my opinion, I think my most outstanding feature is my ability to

accept a compliment.

Because we are so smart, my parents and I are able to see through people as if they were made of hard, clear plastic. We know

what they look like naked and can see the desperate inner workings of their hearts, souls, and intestines. Someone might say,

“How’s it hangin’, big guy,” and I can smell his envy, his fumbling desire to win my good graces with a casual and inappropriate

folksiness that turns my stomach with pity. How’s it hanging, indeed. They know nothing about me and my way of life; and the

world, you see, is filled with people like this.

Take, for example, the reverend, with his trembling hands and waxy jacket of skin. He’s no more complex than one of those

five-piece wooden puzzles given to idiots and school-children. He wants us to sit in the front row so we won’t be a distraction

to the other parishioners, who are always turning in their pews, craning their necks to admire our physical and spiritual

beauty. They’re enchanted by our breeding and want to see firsthand how we’re coping with our tragedy. Everywhere we go, my

parents and I are the center of attention. “It’s them! Look, there’s the son! Touch him, grab for his tie, a lock of his hair,

anything!”

The reverend hoped that by delivering his sermon on horseback, he might regain a bit of attention for himself, but even with

the lariat and his team of prancing Clydesdales, his plan has failed to work. At least with us seated in the front row, the

congregation is finally facing forward, which is a step in the right direction. If it helps bring people closer to God, we’d

be willing to perch on the pipe organ or lash ourselves to the original stainless-steel cross that hangs above the altar.

We’d do just about anything because, despite our recent hardships, our first duty is to help others. The Inner City Picnic

Fund, our Annual Headache Drive, the Polo Injury Wing at the local Memorial Hospital: we give unspeakable amounts to charity,

but you’ll never hear us talk about it. We give anonymously because the sackfuls of thank-you letters break our hearts with

their clumsy handwriting and hopeless phonetic spelling. Word gets out that we’re generous

and

good-looking, and before you know it our front gate will become a campsite for fashion editors and crippled children, who

tend to ruin the grass with the pointy shanks of their crutches. No, we do what we can but with as little fanfare as possible.

You won’t find us waving from floats or marching alongside the Grand Pooh-bah, because that would only draw attention to ourselves.

Oh, you see the hangers-on doing that sort of thing all the time, but it’s cheap and foolish and one day they’ll face the

consequences of their folly. They’re hungry for something they know nothing about, but we, we know all too well that the price

of fame is the loss of privacy. Public displays of happiness only encourage the many kidnappers who prowl the leafy estates

of our better neighborhoods.

When my sisters were taken, my father crumpled the ransom note and tossed it into the eternal flame that burns beside the

mummified Pilgrim we keep in the dining hall of our summer home in Olfactory. We don’t negotiate with criminals, because it’s

not in our character. Every now and then we think about my sisters and hope they’re doing well, but we don’t dwell upon the

matter, as that only allows the kidnappers to win. My sisters are gone for the time being but, who knows, maybe they’ll return

someday, perhaps when they’re older and have families of their own. In the meantime, I am left as the only child and heir

to my parents’ substantial fortune. Is it lonely? Sometimes. I’ve still got my mother and father and, of course, the servants,

several of whom are extraordinarily clever despite their crooked teeth and lack of breeding. Why, just the other day I was

in the stable with Duncan when…

“Oh, for God’s sake,” my mother said, tossing her wooden spoon into a cauldron of chipped-beef gravy. “Leave that goddamned

cat alone before I claw you myself. It’s bad enough you’ve got her tarted up like some two-dollar whore. Take that costume

off her and turn her loose before she runs away just like the last one.”

Adjusting my glasses with my one free hand, I reminded her that the last cat had been hit by a car.

“She did it on purpose,” my mother said. “It was her only way out, and you drove her to it with your bullshit about eating

prime rib with the Kennedys or whatever the hell it was you were yammering on about that day. Go on now, and let her loose.

Then I want you to run out to the backyard and call your sisters out of that ditch. Find your father while you’re at it. If

he’s not underneath his car, he’s probably working on the septic tank. Tell them to get their asses to the table, or they’ll

be eating my goddamned fist for dinner.”

It wasn’t that we were poor. According to my parents, we were far from it, just not far enough from it to meet my needs. I

wanted a home with a moat rather than a fence. In order to get a decent night’s sleep, I needed an airport named in our honor.

“You’re a snob,” my mother would say. “That’s your problem in a hard little nutshell. I grew up around people like you, and

you know what? I couldn’t stand them. Nobody could.”

No matter what we had — the house, the cars, the vacations — it was never enough. Somewhere along the line a terrible mistake

had been made. The life I’d been offered was completely unacceptable, but I never gave up hope that my real family might arrive

at any moment, pressing the doorbell with their white-gloved fingers. “Oh, Lord Chisselchin,” they’d cry, tossing their top

hats in celebration, “thank God we’ve finally found you.”

“It ain’t going to happen,” my mother said. “Believe me, if I was going to steal a baby, I would have taken one that didn’t

bust my ass every time I left my coat lying on the sofa. I don’t know how it happened, but you’re mine. If that’s a big disappointment

for you, just imagine what

I

must feel.”

While my mother grocery-shopped, I would often loiter near the front of the store. It was my hope that some wealthy couple

would stuff me into the trunk of their car. They might torture me for an hour or two, but after learning that I was good with

an iron, surely they would remove my shackles and embrace me as one of their own.

“Any takers?” my mother would ask, wheeling her loaded grocery cart out into the parking lot.

“Don’t you know any childless couples?” I’d ask. “Someone with a pool or a private jet?”

“If I did, you’d be the first one to know.”

My displeasure intensified with the appearance of each new sister.

“You have

how many

children in your family?” the teachers would ask. “I’m guessing you must be Catholic, am I right?”

It seemed that every Christmas my mother was pregnant. The toilet was constantly filled with dirty diapers, and toddlers were

forever padding into my bedroom, disturbing my seashell and wine-bottle collections.

I had no notion of the exact mechanics, but from over-hearing the neighbors, I understood that our large family had something

to do with my mother’s lack of control. It was

her

fault that we couldn’t afford a summerhouse with bay windows and a cliffside tennis court. Rather than improve her social

standing, she chose to spit out children, each one filthier than the last.

It wasn’t until she announced her sixth pregnancy that I grasped the complexity of the situation. I caught her in the bedroom,

crying in the middle of the afternoon.

“Are you sad because you haven’t vacuumed the basement yet?” I asked. “I can do that for you if you want.”

“I know you can,” she said. “And I appreciate your offer. No, I’m sad because, shit, because I’m going to have a baby, but

this is the last one, I swear. After this one I’ll have the doctor tie my tubes and solder the knot just to make sure it’ll

never happen again.”

I had no idea what she was talking about — a tube, a knot, a soldering gun — but I nodded my head as if she and I had just

come to some sort of a private agreement that would later be finalized by a team of lawyers.

“I can do this one more time but I’m going to need your help.” She was still crying in a desperate, sloppy kind of way, but

it didn’t embarrass me or make me afraid. Watching her slender hands positioned like a curtain over her face, I understood

that she needed more than just a volunteer maid. And, oh, I would be that person. A listener, a financial advisor, even a

friend: I swore to be all those things and more in exchange for twenty dollars and a written guarantee that I would always

have my own private bedroom. That’s how devoted I was. And knowing what a good deal she was getting, my mother dried her face

and went off in search of her pocketbook.

When the teacher asked if she might visit with my mother, I touched my nose eight times to the surface of my desk.

“May I take that as a ‘yes’?” she asked.

According to her calculations, I had left my chair twenty-eight times that day. “You’re up and down like a flea. I turn my

back for two minutes and there you are with your tongue pressed against that light switch. Maybe they do that where you come

from, but here in my classroom we don’t leave our seats and lick things whenever we please. That is Miss Chest-nut’s light

switch, and she likes to keep it dry. Would you like me to come over to your house and put my tongue on

your

light switches? Well, would you?”

I tried to picture her in action, but my shoe was calling.

Take me off,

it whispered.

Tap my heel against your forehead three times. Do it now, quick, no one will notice.

“Well?” Miss Chestnut raised her faint, penciled eye-brows. “I’m asking you a question. Would you or would you not want me

licking the light switches in your house?”

I slipped off my shoe, pretending to examine the imprint on the heel.

“You’re going to hit yourself over the head with that shoe, aren’t you?”

It wasn’t “hitting,” it was tapping; but still, how had she known what I was about to do?

“Heel marks all over your forehead,” she said, answering my silent question.