Napoleon in Egypt (46 page)

When Le Père read out his findings at a meeting of the Institute, it was realized that the immediate plan for a canal would have to be shelved. Only later was his error detected: the sea levels were in fact almost the same—a finding which made the digging of the first Suez Canal directly across the isthmus much easier, when it was begun just over fifty years later by the Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps. However, the modern inauguration of this project, and the French involvement in it, certainly originated with Napoleon.

By the time Napoleon, Le Père, Monge and the others had finished tracing the route of the Ptolemaic canal, it was dusk, and they found themselves in some danger. They realized that their presence in the desert had almost certainly been observed by the Bedouin. Napoleon had arranged to meet up with the main party at the village of Ageroud (Al Ajrud), a short distance outside Suez on the caravan route to Cairo, but this was some way off. In his memoirs he described what happened next:

With night approaching, and it being over 20 miles

*

across the desert to the camp, he [Napoleon] set off at full gallop. After losing his way a few times he eventually reached the camp. By now only the three or four on the best horses remained with him, the others all being left behind. Large fires were lit on a mound and on the minaret of the mosque at Ageroud fort; as well as this a cannon was ordered to be fired every quarter of an hour, until 11 o’clock, by which time everyone had fortunately made it back. No one was lost.

14

All the party may finally have made it back to camp, but for at least one of them it had been something of an ordeal. The fifty-two-year-old mathematician Monge was no rider at the best of times, and even on the easy stages of the journey had been forced to travel much of the time in the closed carriage. He had been considerably alarmed by the sight of his leader galloping off into the dark, abandoning him to make his own way, lost in the desert, through the Bedouin-infested night.

Later, on the journey back to Cairo, Napoleon spotted a group of Arabs in the distance. Some of his party rode off after them, and found that they were in fact from a friendly tribe. Captain Doguereau, who was one of the pursuit party, recalled in his journal how in their fright and haste to escape, the Arabs “had lost their weapons in the sand; we found them and gave them back. . . . Napoleon bought several camels from them, and they were greatly pleased to be no longer afraid and instead receive money.”

15

Napoleon later encouraged Eugene Beauharnais to mount one of the camels whilst the others held it down, and all watched with much merriment as Eugene struggled to haul himself aboard. But there was more to this than fooling around. Napoleon now had in mind the formation of a French camel corps, which would initially be used for carrying wounded soldiers across the desert to hospital, and also for warfare against the elusive Bedouin. If this proved successful, he would adapt the camels for more ambitious military use: the long march to India was beginning to take shape in his mind.

At one point on their return from Suez, Napoleon’s party and their armed escort made a detour to attack a Bedouin tribal encampment, whose inhabitants had been harassing the French line of communication across the desert between Cairo and Suez. The encampment was burnt to the ground, hostages were taken, and all the livestock was rounded up.

El-Djabarti described Napoleon’s return to the city: “On Sunday evening the general-in-chief re-entered Cairo; he led in several Bedouin and sheiks whom he had taken hostage. . . . He had conquered [2 villages] and brought with him into the city all the livestock that he found there. The villagers—men, women and children—had followed their livestock all the way to Cairo.”

16

Thus the conqueror of Egypt, the intrepid explorer who had discovered the route of the lost ancient Suez Canal, made his triumphal re-entry into Cairo accompanied by a large dust-cloud of bleating goats, some strings of mangy camels, a column of wailing refugees, and a traumatized mathematician, in the form of Monge prostrated in the darkened interior of his dust-encrusted carriage.

Napoleon now set about laying the plans for his future invasion of India. As he wrote in his memoirs: “It is as far from Cairo to the Indus as it is from Bayonne

*

to Moscow. An army of 60,000 men, mounted on 50,000 camels, carrying with them rations for 50 days and water for six days, would arrive in forty days at the Euphrates, and in four months at the Indus in the midst of the Sikhs, Mahrattas, and the people of Hindustan [India], all impatient to shake off the British yoke which oppresses them.”

17

Here we see the full extent of his ambitions for his camel corps. The sheer volume of this army was equally ambitious, considering he had only arrived in Egypt with at most 40,000 personnel, whose ranks had already been diminished by death and injury. Initially he had counted on swelling the ranks of his army by recruiting disaffected Mamelukes, and even conscripting Egyptians. When such plans were seen to be no longer feasible, he had searched for new ways of increasing his military force in preparation for any invasion of India, eventually pinning his hopes on the slave trade: “It is necessary for us to procure, each year, several thousand blacks from Senaar, and from Darfur, and to incorporate them in the French regiments, at the rate of twenty per company.”

18

Interestingly, Napoleon planned to integrate these black slaves into his army, where they would have been trained by their fellow French soldiers and would have fought alongside them; they would not have been segregated, as were the sepoy regiments in British India, who fought under white officers. His intelligence concerning the slave trade was well informed: Senaar, on the Blue Nile, was a center of the slave trade from East Africa; while Darfur, in what is now western Sudan, was where the caravans bringing slaves from as far afield as West Africa and the Congo set out north for Egypt. A few months later Napoleon would begin putting this plan into action, writing to the Sultan of Darfur: “Please send me, by the first caravan, 2,000 strong and healthy sixteen-year-old black slaves . . . order your caravan to come direct, without stopping en route. I am giving orders for it to travel under our protection the whole way.”

19

At around the same time he wrote to Desaix in Upper Egypt: “I would like, Citizen General, to buy two or three thousand black slaves, all older than sixteen, so as to be able to incorporate them a hundred a time to each battalion. See if there isn’t a way to begin their recruitment from the moment they are purchased. I have no need to stress for you the importance of this undertaking.”

20

Marching to India with a grand army may have been Napoleon’s dream, but his preparations for it were very real.

Napoleon now set about writing to Tippoo Sahib, the sultan of Mysore, who had long been an enemy of the British in India. Tippoo Sahib was regarded by the British as nothing more than a Muslim fanatic; in fact, although he was a warrior he was also a man of considerable culture, whose library at his capital Seringapatam contained a priceless collection of some 2,000 Oriental manuscripts.

*

In his attempts to oppose encroaching British influence in India, he had cultivated the French, even going so far as to embrace some of their revolutionary ideals. A Tree of Liberty had been ceremoniously planted at Seringapatam, and a revolutionary Jacobin Club had been founded. Members pledged death to all tyrants, and the overthrow of all unelected rulers (with the exception of Tippoo Sahib). A delegation had been dispatched across the Indian Ocean to the Isle de France (Mauritius) in the hope of gaining French military assistance against the British. This had arrived in January 1798, and news of its arrival had reached Napoleon before he sailed from Toulon in May.

Napoleon’s letter to Tippoo Sahib, dated January 25, 1799, was brief but supportive, promising much but committing himself to nothing:

You have already learned of my arrival on the banks of the Red Sea with an innumerable and invincible army, filled with the desire to deliver you from the iron yoke of the British.

I take this first opportunity to let you know that I desire you should send me, by way of Moka [Yemen] and Muscat, news of the political situation in which you find yourself. I should be pleased if you can dispatch, to Suez or to Cairo, some able and intelligent man, who has your confidence, with whom I can confer on these matters.

21

This letter was duly dispatched, along with a covering note to the Imam of Muscat: “As you have always been our friend . . . I pray also that you will assist in the conveyance of this letter to Tippoo Sahib, by making sure that it reaches him in India as soon as possible.”

22

Despite this, Napoleon’s letter would take over three months to reach India, and Tippoo Sahib would never receive it. The British authorities had got wind of Tippoo Sahib’s attempt to link up with the French, and in February 1799 decided to launch a pre-emptive strike. By early May the British had surrounded him at Seringapatam, launching their final assault on May 4; in the ensuing massacre Tippoo Sahib was slaughtered. Amongst the officers leading this assault, which would result in the thwarting of Napoleon’s ultimate dream, was the young Colonel Wellesley, who would later become the Duke of Wellington.

XVIII

Pursuit into Upper Egypt

B

Y

now Lower Egypt was gradually becoming pacified by the French army. There were occasional insurrections in the delta which were savagely repressed, and unruly Bedouins continued to harass lines of communication that passed through their desert territory, but the extension of French rule to Suez marked a significant expansion of their power. This port controlled all the pilgrim routes that passed down the Red Sea to Mecca by way of Jeddah—including all those which traversed North Africa from as far afield as Morocco, and those which passed from Syria south across Sinai. Napoleon was keen to protect these pilgrim caravans: a show of French goodwill towards Islam which would demonstrate once and for all that his intentions were friendly.

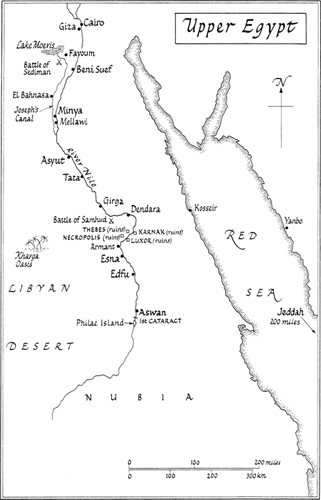

Yet this was only Lower Egypt, whose fertile populous region stretched from Cairo in the south, fanning out across the Nile delta to the coast between Alexandria and Damietta. Besides extending to the Red Sea, French rule also reached into the western desert, where General Andréossy now led an exploratory expedition which reported back to the Institute on the centuries-old Coptic desert monasteries, and the Natron Lakes, whose soda-encrusted shores had been the historic source of embalming chemicals for the ancient Egyptians. In Upper Egypt the situation remained much more fluid. General Desaix had been dispatched south from Cairo as early as August in pursuit of Murad Bey and the Mamelukes who had fled after the Battle of the Pyramids. Napoleon had ordered Desaix to defeat Murad Bey and secure Upper Egypt, a task which was to prove no easy matter. First of all he had to find Murad Bey, who could have been anywhere between Cairo and the Nubian hinterland beyond the First Cataract of the Nile, a territory roughly half the size of France. All Desaix would have at his disposal—even when reinforcements arrived—never amounted to more than 3,000 able-bodied men.

This was to be a campaign which would exploit to the uttermost the skills of its two protagonists. Desaix and Murad Bey were disparate characters, their supreme skills almost complementary, and their encounter would result in a brilliantly conducted campaign of cat and mouse. As we have seen, Desaix’s meteoric rise in the French revolutionary army, as well as his military genius, was second only to that of Napoleon. He was also just as capable of inspiring deep loyalty in his men: witness their behavior on the Rhine when they defied the political commissioner sent by the Directory to arrest him. Such loyalty was curious, for Desaix was hardly a charismatic individual, cutting a distinctly unprepossessing figure in his grubby uniform and with his ugly saber-scarred face. Yet this short, scruffy character, with his straggly hair hanging down over his collar, and his long, drooping mustache, was capable of a certain aristocratic charm. This was used to the full in his womanizing, which was conducted with great and persistent enthusiasm—a side campaign which as we shall see he carried out on a heroic scale during his time in Upper Egypt. His military skills were to prove equally dogged on this campaign: no matter how far he had to go, he would never give up, as Murad Bey would discover to his chagrin. Yet there was so much more to Desaix’s abilities than mere persistence. As no less than the president of the Institute, the great mathematician Fourier, exclaimed admiringly: “Desaix knows all the brilliant military actions down to the least detail. . . . He seems to have felt the need to become immersed in all that is great or useful.”

1