Natasha's Dance (2 page)

25. Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin:

Bathing the Red Horse,

1912. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (photo: Scala, Florence)

Bathing the Red Horse,

1912. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow (photo: Scala, Florence)

26. Kazimir Malevich:

Red Cavalry,

1930. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg (photo: Scala, Florence)

Red Cavalry,

1930. State Russian Museum, St Petersburg (photo: Scala, Florence)

27. Natan Altman:

Portrait of Anna Akhmatova,

1914. Copyright © 2002, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg/Petrushka, Moscow © DACS 2002

Portrait of Anna Akhmatova,

1914. Copyright © 2002, State Russian Museum, St Petersburg/Petrushka, Moscow © DACS 2002

Notes on the Maps and Text

MAPS

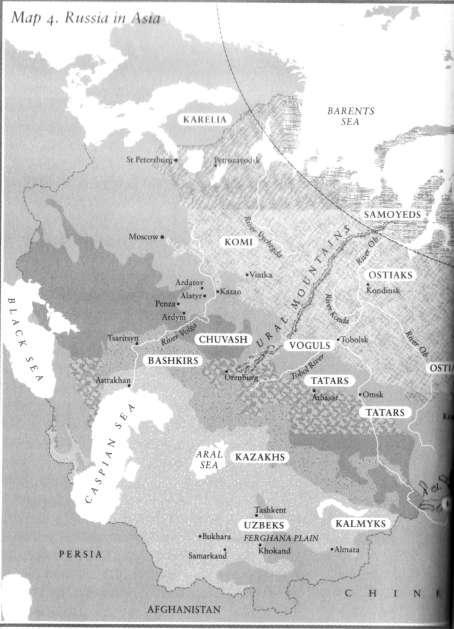

Place names indicated in the maps are those used in Russia before 1917. Soviet names are given in the text where appropriate. Since 1991, most Russian cities have reverted to their pre-revolutionary names.

RUSSIAN NAMES

Russian names are spelled in this book according to the standard (Library of Congress) system of transliteration, but common English spellings of well-known Russian names (Tolstoy and Tchaikovsky, or the Tsar Peter, for example) are retained. To aid pronounciation some Russian names (Vasily, for example) are slightly changed (in this case, from Vasilii).

DATES

From 1700 until 1918 Russia adhered to the Julian calendar, which ran thirteen days behind the Gregorian calendar in use in western Europe. Dates in this book are given according to the Julian calendar until February 1918, when Soviet Russia switched to the Gregorian calendar.

USE OF METRIC

All measurements of distance, weight and area are given in the metric system.

NOTES

Literary works cited in this hook are, wherever possible, from an English-language translation available in bookshops.

Maps

INTRODUCTION

In Tolstoy’s

War and Peace

there is a famous and rather lovely scene where Natasha Rostov and her brother Nikolai are invited by their ‘Uncle’ (as Natasha calls him) to his simple wooden cabin at the end of a day’s hunting in the woods. There the noble-hearted and eccentric ‘Uncle’ lives, a retired army officer, with his housekeeper Anisya, a stout and handsome serf from his estate, who, as it becomes clear from the old man’s tender glances, is his unofficial ‘wife’. Anisya brings in a tray loaded with homemade Russian specialities: pickled mushrooms, rye-cakes made with buttermilk, preserves with honey, sparkling mead, herb-brandy and different kinds of vodka. After they have eaten, the strains of a

balalaika

become audible from the hunting servants’ room. It is not the sort of music that a countess should have liked, a simple country ballad, but seeing how his niece is moved by it, ‘Uncle’ calls for his guitar, blows the dust off it, and with a wink at Anisya, he begins to play, with the precise and accelerating rhythm of a Russian dance, the well-known love song, ‘Came a maiden down the street’. Though Natasha has never before heard the folk song, it stirs some unknown feeling in her heart. ‘Uncle’ sings as the peasants do, with the conviction that the meaning of the song lies in the words and that the tune, which exists only to emphasize the words, ‘comes of itself. It seems to Natasha that this direct way of singing gives the air the simple charm of birdsong. ‘Uncle’ calls on her to join in the folk dance.

War and Peace

there is a famous and rather lovely scene where Natasha Rostov and her brother Nikolai are invited by their ‘Uncle’ (as Natasha calls him) to his simple wooden cabin at the end of a day’s hunting in the woods. There the noble-hearted and eccentric ‘Uncle’ lives, a retired army officer, with his housekeeper Anisya, a stout and handsome serf from his estate, who, as it becomes clear from the old man’s tender glances, is his unofficial ‘wife’. Anisya brings in a tray loaded with homemade Russian specialities: pickled mushrooms, rye-cakes made with buttermilk, preserves with honey, sparkling mead, herb-brandy and different kinds of vodka. After they have eaten, the strains of a

balalaika

become audible from the hunting servants’ room. It is not the sort of music that a countess should have liked, a simple country ballad, but seeing how his niece is moved by it, ‘Uncle’ calls for his guitar, blows the dust off it, and with a wink at Anisya, he begins to play, with the precise and accelerating rhythm of a Russian dance, the well-known love song, ‘Came a maiden down the street’. Though Natasha has never before heard the folk song, it stirs some unknown feeling in her heart. ‘Uncle’ sings as the peasants do, with the conviction that the meaning of the song lies in the words and that the tune, which exists only to emphasize the words, ‘comes of itself. It seems to Natasha that this direct way of singing gives the air the simple charm of birdsong. ‘Uncle’ calls on her to join in the folk dance.

’Now then, niece!’ he exclaimed, waving to Natasha the hand that had just struck a chord. Natasha threw off the shawl from her shoulders, ran forward to face

’Uncle’, and setting her arms akimbo, also made a motion with her shoulders and struck an attitude.

Where, how, and when had this young countess, educated by an

emigree

French governess, imbibed from the Russian air she breathed that spirit, and obtained that manner which the

pas de chale

would, one would have supposed, long ago have effaced? But the spirit and the movements were those inimitable and unteachable Russian ones that ‘Uncle’ had expected of her. As soon as she had struck her pose and smiled triumphantly, proudly, and with sly merriment, the fear that had at first seized Nikolai and the others that she might not do the right thing was at an end, and they were all already admiring her.

emigree

French governess, imbibed from the Russian air she breathed that spirit, and obtained that manner which the

pas de chale

would, one would have supposed, long ago have effaced? But the spirit and the movements were those inimitable and unteachable Russian ones that ‘Uncle’ had expected of her. As soon as she had struck her pose and smiled triumphantly, proudly, and with sly merriment, the fear that had at first seized Nikolai and the others that she might not do the right thing was at an end, and they were all already admiring her.

She did the right thing with such precision, such complete precision, that Anisya Fyodorovna, who had at once handed her the handkerchief she needed for the dance, had tears in her eyes, though she laughed as she watched this slim, graceful countess, reared in silks and velvets and so different from herself, who yet was able to understand all that was in Anisya and in Anisya’s father and mother and aunt, and in every Russian man and woman.

1

1

What enabled Natasha to pick up so instinctively the rhythms of the dance? How could she step so easily into this village culture from which, by social class and education, she was so far removed? Are we to suppose, as Tolstoy asks us to in this romantic scene, that a nation such as Russia may be held together by the unseen threads of a native sensibility? The question takes us to the centre of this book. It calls itself a cultural history. But the elements of culture which the reader will find here are not just great creative works like

War and Peace

but artefacts as well, from the folk embroidery of Natasha’s shawl to the musical conventions of the peasant song. And they are summoned, not as monuments to art, but as impressions of the national consciousness, which mingle with politics and ideology, social customs and beliefs, folklore and religion, habits and conventions, and all the other mental bric-a-brac that constitute a culture and a way of life. It is not my argument that art can serve the purpose of a window on to life. Natasha’s dancing scene cannot be approached as a literal record of experience, though memoirs of this period show that there were indeed noblewomen who picked up village dances in this way.

2

But art can be looked at as a record of belief- in this case, the write’s yearning for

War and Peace

but artefacts as well, from the folk embroidery of Natasha’s shawl to the musical conventions of the peasant song. And they are summoned, not as monuments to art, but as impressions of the national consciousness, which mingle with politics and ideology, social customs and beliefs, folklore and religion, habits and conventions, and all the other mental bric-a-brac that constitute a culture and a way of life. It is not my argument that art can serve the purpose of a window on to life. Natasha’s dancing scene cannot be approached as a literal record of experience, though memoirs of this period show that there were indeed noblewomen who picked up village dances in this way.

2

But art can be looked at as a record of belief- in this case, the write’s yearning for

a broad community with the Russian peasantry which Tolstoy shared with the ‘men of 1812’, the liberal noblemen and patriots who dominate the public scenes of

War and Peace.

War and Peace.

Russia invites the cultural historian to probe below the surface of artistic appearance. For the past two hundred years the arts in Russia have served as an arena for political, philosophical and religious debate in the absence of a parliament or a free press. As Tolstoy wrote in ‘A Few Words on

War and Peace’

(1868), the great artistic prose works of the Russian tradition were not novels in the European sense.

3

They were huge poetic structures for symbolic contemplation, not unlike icons, laboratories in which to test ideas; and, like a science or religion, they were animated by the search for truth. The overarching subject of all these works was Russia - its character, its history, its customs and conventions, its spiritual essence and its destiny. In a way that was extraordinary, if not unique to Russia, the country’s artistic energy was almost wholly given to the quest to grasp the idea of its nationality. Nowhere has the artist been more burdened with the task of moral leadership and national prophecy, nor more feared and persecuted by the state. Alienated from official Russia by their politics, and from peasant Russia by their education, Russia’s artists took it upon themselves to create a national community of values and ideas through literature and art. What did it mean to be a Russian? What was Russia’s place and mission in the world? And where was the true Russia? In Europe or in Asia? St Petersburg or Moscow? The Tsar’s empire or the muddy one-street village where Natasha’s ‘Uncle’ lived? These were the ‘accursed questions’ that occupied the mind of every serious writer, literary critic and historian, painter and composer, theologian and philosopher in the golden age of Russian culture from Pushkin to Pasternak. They are the questions that lie beneath the surface of the art within this book. The works discussed here represent a history of ideas and attitudes - concepts of the nation through which Russia tried to understand itself. If we look carefully, they may become a window on to a nation’s inner life.

War and Peace’

(1868), the great artistic prose works of the Russian tradition were not novels in the European sense.

3

They were huge poetic structures for symbolic contemplation, not unlike icons, laboratories in which to test ideas; and, like a science or religion, they were animated by the search for truth. The overarching subject of all these works was Russia - its character, its history, its customs and conventions, its spiritual essence and its destiny. In a way that was extraordinary, if not unique to Russia, the country’s artistic energy was almost wholly given to the quest to grasp the idea of its nationality. Nowhere has the artist been more burdened with the task of moral leadership and national prophecy, nor more feared and persecuted by the state. Alienated from official Russia by their politics, and from peasant Russia by their education, Russia’s artists took it upon themselves to create a national community of values and ideas through literature and art. What did it mean to be a Russian? What was Russia’s place and mission in the world? And where was the true Russia? In Europe or in Asia? St Petersburg or Moscow? The Tsar’s empire or the muddy one-street village where Natasha’s ‘Uncle’ lived? These were the ‘accursed questions’ that occupied the mind of every serious writer, literary critic and historian, painter and composer, theologian and philosopher in the golden age of Russian culture from Pushkin to Pasternak. They are the questions that lie beneath the surface of the art within this book. The works discussed here represent a history of ideas and attitudes - concepts of the nation through which Russia tried to understand itself. If we look carefully, they may become a window on to a nation’s inner life.

Natasha’s dance is one such opening. At its heart is an encounter

between two entirely different worlds: the European culture of the

upper classes and the Russian culture of the peasantry. The war of

1812 was the first moment when the two moved together in a national

formation. Stirred by the patriotic spirit of the serfs, the aristocracy of Natasha’s generation began to break free from the foreign conventions of their society and search for a sense of nationhood based on ‘Russian’ principles. They switched from speaking French to their native tongue; they Russified their customs and their dress, their eating habits and their taste in interior design; they went out to the countryside to learn folklore, peasant dance and music, with the aim of fashioning a national style in all their arts to reach out to and educate the common man; and, like Natasha’s ‘Uncle’ (or indeed her brother at the end of

War and Peace),

some of them renounced the court culture of St Petersburg and tried to live a simpler (more ‘Russian’) way of life alongside the peasantry on their estates.

War and Peace),

some of them renounced the court culture of St Petersburg and tried to live a simpler (more ‘Russian’) way of life alongside the peasantry on their estates.

The complex interaction between these two worlds had a crucial influence on the national consciousness and on all the arts in the nineteenth century. That interaction is a major feature of this book. But the story which it tells is not meant to suggest that a single ‘national’ culture was the consequence. Russia was too complex, too socially divided, too politically diverse, too ill-defined geographically, and perhaps too big, for a single culture to be passed off as the national heritage. It is rather my intention to rejoice in the sheer diversity of Russia’s cultural forms. What makes the Tolstoy passage so illuminating is the way in which it brings so many different people to the dance: Natasha and her brother, to whom this strange but enchanting village world is suddenly revealed; their ‘Uncle’, who lives in this world but is not a part of it; Anisya, who is a villager yet who also lives with ‘Uncle’ at the margins of Natasha’s world; and the hunting servants and the other household serfs, who watch, no doubt with curious amusement (and perhaps with other feelings, too), as the beautiful countess performs their dance. My aim is to explore Russian culture in the same way Tolstoy presents Natasha’s dance: as a series of encounters or creative social acts which were performed and understood in many different ways.

To view a culture in this refracted way is to challenge the idea of a pure, organic or essential core. There was no ‘authentic’ Russian peasant dance of the sort imagined by Tolstoy and, like the melody to which Natasha dances, most of Russia’s ‘folk songs’ had in fact come

from the towns.

4

Other elements of the village culture Tolstoy pictured

4

Other elements of the village culture Tolstoy pictured

may have come to Russia from the Asiatic steppe - elements that had been imported by the Mongol horsemen who ruled Russia from the thirteenth century to the fifteenth century and then mostly settled down in Russia as tradesmen, pastoralists and agriculturalists. Natasha’s shawl was almost certainly a Persian one; and, although Russian peasant shawls were coming into fashion after 1812, their ornamental motifs were probably derived from oriental shawls. The

balalaika

was descended from the

dombra,

a similar guitar of Central Asian origin (it is still widely used in Kazakh music), which came to Russia in the sixteenth century.

5

The Russian peasant dance tradition was itself derived from oriental forms, in the view of some folklorists in the nineteenth century. The Russians danced in lines or circles rather than in pairs, and the rhythmic movements were performed by the hands and shoulders as well as by the feet, with great importance being placed in female dancing on subtle doll-like gestures and the stillness of the head. Nothing could have been more different from the waltz Natasha danced with Prince Andrei at her first ball, and to mimic all these movements must have felt as strange to her as it no doubt appeared to her peasant audience. But if there is no ancient Russian culture to be excavated from this village scene, if much of any culture is imported from abroad, then there is a sense in which Natasha’s dance is an emblem of the view to be taken in this book: there is no

quintessential

national culture, only mythic images of it, like Natasha’s version of the peasant dance.

balalaika

was descended from the

dombra,

a similar guitar of Central Asian origin (it is still widely used in Kazakh music), which came to Russia in the sixteenth century.

5

The Russian peasant dance tradition was itself derived from oriental forms, in the view of some folklorists in the nineteenth century. The Russians danced in lines or circles rather than in pairs, and the rhythmic movements were performed by the hands and shoulders as well as by the feet, with great importance being placed in female dancing on subtle doll-like gestures and the stillness of the head. Nothing could have been more different from the waltz Natasha danced with Prince Andrei at her first ball, and to mimic all these movements must have felt as strange to her as it no doubt appeared to her peasant audience. But if there is no ancient Russian culture to be excavated from this village scene, if much of any culture is imported from abroad, then there is a sense in which Natasha’s dance is an emblem of the view to be taken in this book: there is no

quintessential

national culture, only mythic images of it, like Natasha’s version of the peasant dance.

It is not my aim to ‘deconstruct’ these myths; nor do I wish to claim, in the jargon used by academic cultural historians these days, that Russia’s nationhood was no more than an intellectual ‘construction’. There was a Russia that was real enough - a Russia that existed before ‘Russia’ or ‘European Russia’, or any other myths of the national identity. There was the historical Russia of ancient Muscovy, which had been very different from the West, before Peter the Great forced it to conform to European ways in the eighteenth century. During Tolstoy’s lifetime, this old Russia was still animated by the traditions of the Church, by the customs of the merchants and many of the gentry on the land, and by the empire’s

60

million peasants, scattered in half a million remote villages across the forests and the steppe, whose way of life remained little changed for centuries. It is the heartbeat of this

60

million peasants, scattered in half a million remote villages across the forests and the steppe, whose way of life remained little changed for centuries. It is the heartbeat of this

Other books

Sparking the Fire by Kate Meader

Dear Sir, I'm Yours by Burkhart, Joely Sue

Pushed to the Edge (SEAL Team 14) by Mathis, Loren

The Book of the Lion by Michael Cadnum

Making Magic by Donna June Cooper

The Going Down of the Sun by Jo Bannister

Perilous by E. H. Reinhard

The League of Seven by Alan Gratz

Sugar Springs by Law, Kim

Down Solo by Earl Javorsky