Natasha's Dance (49 page)

(for, as the peasants said, all marriages were ‘forged’). Then came the prenuptial rituals like the washing of the bride and the

devicbnik

(the unplaiting of the maiden’s braid), accompanied by more laments, which were followed on the morning of the wedding by the blessing of the bride with the family icon and then, amid the wailing of the village girls, her departure for the church. Finally there was the wedding ceremony itself, followed by the marriage feast. Stravinsky rearranged these rituals into four tableaux in a way that emphasized the coming together of the bride and groom as ‘two rivers into one’:1) ‘At the Bride’s’; 2) ‘At the Groom’s’; 3) ‘Seeing off the Bride’; and 4) ‘The Wedding Feast’. The peasant wedding was taken as a symbol of the family’s communion in the village culture of these ancient rituals. It was portrayed as a collective rite - the binding of the bridal couple to the patriarchal culture of the peasant community - rather than as a romantic union between two individuals.

devicbnik

(the unplaiting of the maiden’s braid), accompanied by more laments, which were followed on the morning of the wedding by the blessing of the bride with the family icon and then, amid the wailing of the village girls, her departure for the church. Finally there was the wedding ceremony itself, followed by the marriage feast. Stravinsky rearranged these rituals into four tableaux in a way that emphasized the coming together of the bride and groom as ‘two rivers into one’:1) ‘At the Bride’s’; 2) ‘At the Groom’s’; 3) ‘Seeing off the Bride’; and 4) ‘The Wedding Feast’. The peasant wedding was taken as a symbol of the family’s communion in the village culture of these ancient rituals. It was portrayed as a collective rite - the binding of the bridal couple to the patriarchal culture of the peasant community - rather than as a romantic union between two individuals.

It was a commonplace in the Eurasian circles in which Stravinsky moved in Paris that the greatest strength of the Russian people, and the thing that set them apart from the people of the West, was their voluntary surrender of the individual will to collective rituals and forms of life. This sublimation of the individual was precisely what had attracted Stravinsky to the subject of the ballet in the first place -it was a perfect vehicle for the sort of peasant music he had been composing since

The Rite of Spring.

In

The Peasant Wedding

there was no room for emotion in the singing parts. The voices were supposed to merge as one, as they did in church chants and peasant singing, to create a sound Stravinsky once described as ‘perfectly homogeneous, perfectly impersonal, and perfectly mechanical’. The same effect was produced by the choice of instruments (the result of a ten-year search for an essential ‘Russian’ sound): four pianos (on the stage), cimbalom and bells and percussion instruments - all of which were scored to play ‘mechanically’. The reduced size and palette of the orchestra (it was meant to sound like a peasant wedding band) were reflected in the muted colours of Goncharova’s sets. The great colourist abandoned the vivid reds and bold peasant patterns of her original designs for the minimalist pale blue of the sky and the deep browns of the earth which were used in the production. The choreography (by Bronislava Nijinska) was equally impersonal - the

corps de ballet

moving all as

The Rite of Spring.

In

The Peasant Wedding

there was no room for emotion in the singing parts. The voices were supposed to merge as one, as they did in church chants and peasant singing, to create a sound Stravinsky once described as ‘perfectly homogeneous, perfectly impersonal, and perfectly mechanical’. The same effect was produced by the choice of instruments (the result of a ten-year search for an essential ‘Russian’ sound): four pianos (on the stage), cimbalom and bells and percussion instruments - all of which were scored to play ‘mechanically’. The reduced size and palette of the orchestra (it was meant to sound like a peasant wedding band) were reflected in the muted colours of Goncharova’s sets. The great colourist abandoned the vivid reds and bold peasant patterns of her original designs for the minimalist pale blue of the sky and the deep browns of the earth which were used in the production. The choreography (by Bronislava Nijinska) was equally impersonal - the

corps de ballet

moving all as

one, like some vast machine made of human beings, and carrying the whole of the storyline. ‘There were no leading parts’, Nijinska explained; ‘each member would blend through the movement into the whole… [and] the action of the separate characters would be expressed, not by each one individually, but rather by the action of the whole ensemble.’

150

It was the perfect ideal of the Russian peasantry.

150

It was the perfect ideal of the Russian peasantry.

5

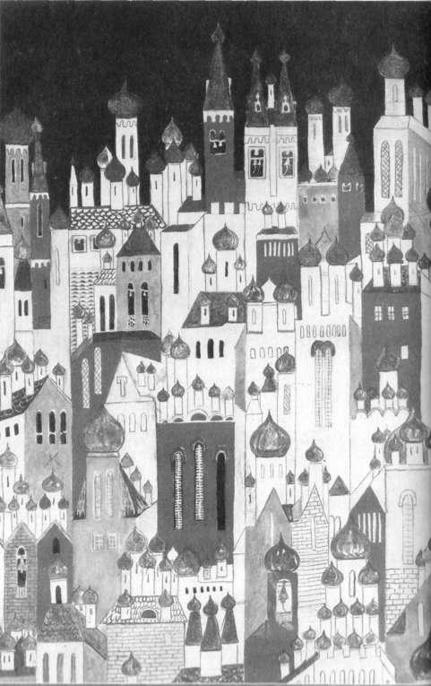

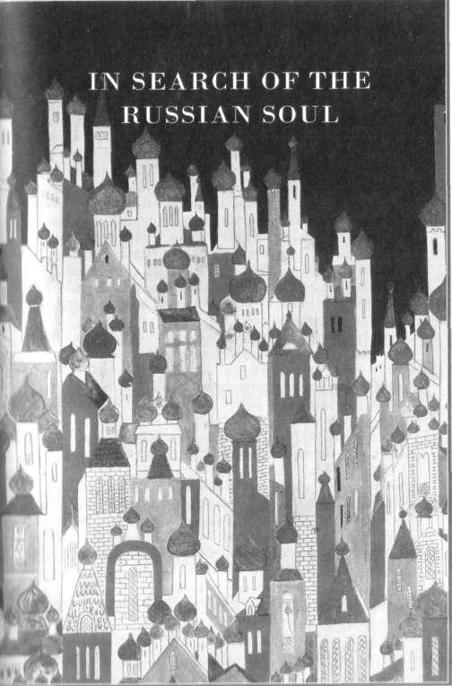

overleaf:

Natalia Goncharova: backdrop design

for The

Firebird

(1926)

Firebird

(1926)

1

The monastery of Optina Pustyn nestles peacefully between the pine forests and the meadows of the Zhizdra river near the town of Kozelsk in Kaluga province, 200 kilometres or so south of Moscow. The whitewashed walls of the monastery and the intense blue of its cupolas, with their golden crosses sparkling in the sun, can be seen for miles against the dark green background of the trees. The monastery was cut off from the modern world, inaccessible by railway or by road in the nineteenth century, and pilgrims who approached the holy shrine, by river boat or foot, or by crawling on their knees, were often overcome by the sensation of travelling back in time. Optina Pustyn was the last great refuge of the hermitic tradition that connected Russia with Byzantium, and it came to be regarded as the spiritual centre of the national consciousness. All the greatest writers of the nineteenth century - Gogol, Dostoevsky and Tolstoy among them - came here in their search for the ‘Russian soul’.

The monastery was founded in the fourteenth century. But it did not become well known until the beginning of the nineteenth century, when it was at the forefront of a revival in the medieval hermitic tradition and a hermitage, or skete, was built within its walls. The building of the skete was a radical departure from the Spiritual Regulations of the Holy Synod, which had banned such hermitages since 1721. The Spiritual Regulations were a sort of constitution of the Church. They were anything but spiritual. It was the Regulations which established the subordination of the Church to the Imperial state. The Church was governed by the Holy Synod, a body of laymen and clergy appointed by the Tsar to replace the Patriarchate, which was abolished in 1721. The duty of the clergy, as set out in the Regulations, was to uphold and enforce the Tsar’s authority, to read out state decrees from the pulpit, to carry out administrative duties for the state, and inform the police about all dissent and criminality, even if such information had been obtained through the confessional. The Church, for the most part, was a faithful tool in the hands of the Tsar. It was not in its interests to rock the boat. During the eighteenth century a large proportion of its lands had been taken from it by the

state, so the Church was dependent on the state’s finances to support the parish clergy and their families.* Impoverished and venal, badly educated and proverbially fat, the parish priest was no advertisement for the established Church. As its spiritual life declined, people broke away from the official Church to join the Old Believers or the diverse sects which flourished from the eighteenth century by offering a more obviously religious way of life.

Within the Church, meanwhile, there was a growing movement of revivalists who looked to the traditions of the ancient monasteries like Optina for a spiritual rebirth. Church and state authorities alike were wary of this revivalist movement in the monasteries. If the monastic clergy were allowed to set up their own communities of Christian brotherhood, with their own pilgrim followings and sources of income, they could become a source of spiritual dissent from the established doctrines of Church and state. There would be no control on the social influence or moral teaching of the monasteries. At Optina, for example, there was a strong commitment to give alms and spiritual comfort to the poor which attracted a mass following. None the less, certain sections of the senior clergy displayed a growing interest in the mystical ideas of Russia’s ancient hermits. The ascetic principles of Father Paissy, who led this Church revival in the latter part of the eighteenth century, were in essence a return to the hesychastic path of Russia’s most revered medieval monks.

Hesychasm has its roots in the Orthodox conception of divine grace. In contrast to the Western view that grace is conferred on the virtuous or on those whom God has so ordained, the Orthodox religion regards grace as a natural state, implied in the act of creation itself, and therefore potentially available to any human being merely by virtue of having been created by the Lord. In this view the way the believer approaches God is through the consciousness of his own spiritual personality and by studying the example of Christ in order to cope better with the dangers that await him on his journey through life. The hesychastic monks believed that they could find a way to God in their own hearts - by practising a life of poverty and prayer with the spiritual

* Unlike their Catholic counterpart!, Russian Orthodox priests were allowed to marry. Only the monastic clergy were not.

guidance of a ‘holy man’ or ‘elder’ who was in touch with the ‘energies’ of God. The great flowering of this doctrine came in the late fifteenth century, when the monk Nil Sorsky denounced the Church for owning land and serfs. He left his monastery to become a hermit in the wilderness of the Volga’s forest lands. His example was an inspiration to thousands of hermits and schismatics. Fearful that Sorsky’s doctrine of poverty might provide the basis for a social revolution, the Church suppressed the hesychastic movement. But Sorsky’s ideas re-emerged in the eighteenth century, when clergymen like Paissy began to look again for a more spiritual church.

Paissy’s ideas were gradually embraced in the early decades of the nineteenth century by clergy who saw them as a general return to ‘ancient Russian principles’. In 1822, just over one hundred years after it had been imposed, the ban on sketes was lifted and a hermitage was built at Optina Pustyn, where Father Paissy’s ideas had their greatest influence. The skete was the key to the renaissance of the monastery in the nineteenth century. Here was its inner sanctuary where up to thirty hermits lived in individual cells, in silent contemplation and in strict obedience to the elder, or

starets,

of the monastery.

1

Three great elders, each a disciple of Father Paissy and each in turn renowned for his devout ways, made Optina famous in its golden age: Father Leonid was the elder of the monastery from 1829; Father Makary from 1841; and Father Amvrosy from 1860 to 1891. It was the charisma of these elders that made the monastery so extraordinary - a sort of ‘clinic for the soul’ - drawing monks and other pilgrims in their thousands from all over Russia every year. Some came to the elder for spiritual guidance, to confess their doubts and seek advice; others for his blessing or a cure. There was even a separate settlement, just outside the walls of the monastery, where people came to live so that they could see the elder every day.

2

The Church was wary of the elders’ popularity. It was fearful of the saint-like status they enjoyed among their followers, and it did not know enough about their spiritual teachings, especially their cult of poverty and their broadly social vision of a Christian brotherhood, to say for sure that they were not a challenge to the established Church. Leonid met with something close to persecution in his early years. The diocesan authorities tried to stop the crowds of pilgrims from visiting the elder in the monastery. They put

starets,

of the monastery.

1

Three great elders, each a disciple of Father Paissy and each in turn renowned for his devout ways, made Optina famous in its golden age: Father Leonid was the elder of the monastery from 1829; Father Makary from 1841; and Father Amvrosy from 1860 to 1891. It was the charisma of these elders that made the monastery so extraordinary - a sort of ‘clinic for the soul’ - drawing monks and other pilgrims in their thousands from all over Russia every year. Some came to the elder for spiritual guidance, to confess their doubts and seek advice; others for his blessing or a cure. There was even a separate settlement, just outside the walls of the monastery, where people came to live so that they could see the elder every day.

2

The Church was wary of the elders’ popularity. It was fearful of the saint-like status they enjoyed among their followers, and it did not know enough about their spiritual teachings, especially their cult of poverty and their broadly social vision of a Christian brotherhood, to say for sure that they were not a challenge to the established Church. Leonid met with something close to persecution in his early years. The diocesan authorities tried to stop the crowds of pilgrims from visiting the elder in the monastery. They put

20. Hermits at a monastery in northern Russia. Those standing have taken

the vows of the schema (skhima)

,

the strictest monastic rules in the

,

the strictest monastic rules in the

Orthodox Church. Their habits show the instruments of the martyrdom of

Christ and a text in Church Slavonic from Luke 9:24

up Father Vassian, an old monk at Optina (and the model for Father Ferrapont in

The Brothers Karamazov),

to denounce Leonid in several published tracts.

3

Yet the elders were to survive as an institution. They were held in high esteem by the common people, and they gradually took root in Russia’s monasteries, albeit as a spiritual force that spilled outside the walls of the official Church.

The Brothers Karamazov),

to denounce Leonid in several published tracts.

3

Yet the elders were to survive as an institution. They were held in high esteem by the common people, and they gradually took root in Russia’s monasteries, albeit as a spiritual force that spilled outside the walls of the official Church.

It was only natural that the nineteenth-century search for a true Russian faith should look back to the mysticism of medieval monks. Here was a form of religious consciousness that seemed to touch a chord in the Russian people, a form of consciousness that was somehow more essential and emotionally charged than the formalistic religion of the official Church. Here, moreover, was a faith in sympathy with the Romantic sensibility. Slavophiles like Kireevsky, who began the pilgrimage of intellectuals to Optina, discovered a reflection of their own Romantic aversion to abstract reason in the anti-rational approach to the divine mystery which they believed to be the vital feature of the Russian Church and preserved at its purest in the monasteries. They saw the monastery as a religious version of their own striving for community - a sacred microcosm of their ideal Russia - and on that basis they defined the Church as a spiritual union of the Orthodox, the true community of Christian love that was only to be found in the Russian Church. This was a Slavophile mythology, of course, but there was a core of mysticism in the Russian Church. Unlike the Western Churches, whose theology is based on a reasoned understanding of divinity, the Russian Church believes that God cannot be grasped by the human mind (for anything we can know is inferior to Him) and that even to discuss God in such human categories is to reduce the Divine Mystery of His revelation. The only way to approach the Russian God is through the spiritual transcendence of this world.

4

4

Other books

Cars 2 by Irene Trimble

The Iron Chancellor by Robert Silverberg

IGMS Issue 4 by IGMS

The Fall Musical by Peter Lerangis

The Dating Deal by Melanie Marks

The Freedman and the Pharaoh's Staff by Lane Heymont

Free Spirits by Julia Watts

Mad Lizard Mambo by Rhys Ford

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Other Jazz Age Stories by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Riotous Assembly by Tom Sharpe