Natasha's Dance (86 page)

It may seem extraordinary that films like

Stalker

and

Solaris

were produced in the Brezhnev era, when all forms of organized religion were severely circumscribed and the deadening orthodoxy of ‘Developed Socialism’ held the country’s politics in its grip. But within the Soviet monolith there were many different voices that called for a return to ‘Russian principles’. One was the literary journal

Molodaia gvardiia (Young Guard),

which acted as a forum for Russian nationalists and conservationists, defenders of the Russian Church, and neo-Populists like the ‘village prose writers’ Fedor Abramov and Valentin Rasputin, who painted a nostalgic picture of the countryside and idealized the honest working peasant as the true upholder of the Russian soul and its mission in the world.

Molodaia gvardiia

enjoyed

Stalker

and

Solaris

were produced in the Brezhnev era, when all forms of organized religion were severely circumscribed and the deadening orthodoxy of ‘Developed Socialism’ held the country’s politics in its grip. But within the Soviet monolith there were many different voices that called for a return to ‘Russian principles’. One was the literary journal

Molodaia gvardiia (Young Guard),

which acted as a forum for Russian nationalists and conservationists, defenders of the Russian Church, and neo-Populists like the ‘village prose writers’ Fedor Abramov and Valentin Rasputin, who painted a nostalgic picture of the countryside and idealized the honest working peasant as the true upholder of the Russian soul and its mission in the world.

Molodaia gvardiia

enjoyed

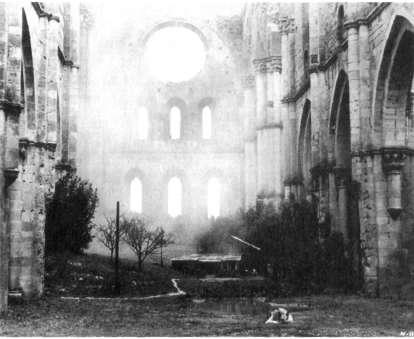

30.

‘The Russian bouse inside the Italian cathedral’. Final shot from Andrei Tarkovsky’s

Nostalgia

(1983)

‘The Russian bouse inside the Italian cathedral’. Final shot from Andrei Tarkovsky’s

Nostalgia

(1983)

the support of the Party’s senior leadership throughout the 1970s.* Yet its cultural politics were hardly communist; and at times, such as in its opposition to the demolition of churches and historic monuments, or in the controversial essays it published by the nationalist painter Ilya Glazunov which explicitly condemned the October Revolution as an interruption of the national tradition, it was even anti-Soviet. The journal had links with opposition groups in the Russian Church, the conservation movement (which numbered several million members in

* It had the political protection of Politburo member Mikhail Suslov, Brezhnev’s chief of ideology. When Alexander Yakovlev attacked

Molodaia gvardiia

as anti-Leninist on account of its nationalism and religious emphasis, Suslov succeeded in winning Brezhnev over to the journal’s side. Yakovlev was sacked from the Party’s Propaganda Department. In 1973, he was dismissed from the Central Committee and appointed Soviet ambassador to Canada (from where he would return to become Gorbachev’s chief ideologist).

Molodaia gvardiia

as anti-Leninist on account of its nationalism and religious emphasis, Suslov succeeded in winning Brezhnev over to the journal’s side. Yakovlev was sacked from the Party’s Propaganda Department. In 1973, he was dismissed from the Central Committee and appointed Soviet ambassador to Canada (from where he would return to become Gorbachev’s chief ideologist).

the 1960s) and the dissident intelligentsia. Even Solzhenitsyn came to its defence when it was attacked by the journal

Novy mir

(the very journal which had made his name by publishing

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

in 1962).

207

In the 1970s Russian nationalism was a growing movement, which commanded the support of Party members and dissidents alike. There were several journals like

Molo-daia gvardiia

- some official, others dissident and published underground

(samizdat)

- and a range of state and voluntary associations, from literary societies to conservation groups, which forged a broad community on ‘Russian principles’. As the editor of the

samizdat

journal

Veche

put it in his first editorial in 1971: ‘In spite of everything, there are still Russians. It is not too late to return to the homeland.’

208

Novy mir

(the very journal which had made his name by publishing

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

in 1962).

207

In the 1970s Russian nationalism was a growing movement, which commanded the support of Party members and dissidents alike. There were several journals like

Molo-daia gvardiia

- some official, others dissident and published underground

(samizdat)

- and a range of state and voluntary associations, from literary societies to conservation groups, which forged a broad community on ‘Russian principles’. As the editor of the

samizdat

journal

Veche

put it in his first editorial in 1971: ‘In spite of everything, there are still Russians. It is not too late to return to the homeland.’

208

What, in the end, was ‘Soviet culture’? Was it anything? Can one ever say that there was a specific Soviet genre in the arts? The avant-garde of the 1920s, which borrowed a great deal from Western Europe, was really a continuation of the modernism of the turn of century. It was revolutionary, in many ways more so than the Bolshevik regime, but in the end it was not compatible with the Soviet state, which could never have been built on artists’ dreams. The idea of constructing Soviet culture on a ‘proletarian’ foundation was similarly unsustainable -although that was surely the one idea of culture that was intrinsically ‘Soviet’: factory whistles don’t make music (and what, in any case, is ‘proletarian art’?). Socialist Realism was also, arguably, a distinctively Soviet art form. Yet a large part of it was a hideous distortion of the nineteenth-century tradition, not unlike the art of the Third Reich or of fascist Italy. Ultimately the ‘Soviet’ element (which boiled down to the deadening weight of ideology) added nothing to the art.

The Georgian film director Otar loseliani recalls a conversation with the veteran film-maker Boris Barnet in 1962:

He asked me: ‘Who are you?’ I said, ‘A director’… ‘Soviet’, he corrected, ‘you must always say “Soviet director”. It is a very special profession.’ ‘In what way?’ I asked. ‘Because if you ever manage to become honest, which would surprise me, you can remove the word “Soviet”.’

205

205

8

From beneath such ruins I speak,

From beneath such an avalanche I cry,

As if under the vault of a fetid cellar

I were burning in quicklime.

I will pretend to be soundless this winter

And I will slam the eternal doors forever,

And even so, they will recognize my voice,

And even so they will believe in it once more.

210

210

Anna Akhmatova was one of the great survivors. Her poetic voice was irrepressible. In the last ten years of her long life, beginning with the release of her son from the gulag in 1956, Akhmatova enjoyed a relatively settled existence. She was fortunate enough to retain her capacity for writing poetry until the end.

In 1963 she wrote the last additions to her masterpiece,

Poem without a Hero,

which she had started writing in 1940. Isaiah Berlin, to whom she read the poem at the Fountain House in 1945, described it as a ‘kind of final memorial to her life as a poet and the past of the city - St Petersburg - which was part of her being’.

211

The poem conjures up, in the form of a carnival procession of masked characters which appears before the author at the Fountain House, a whole generation of vanished friends and figures from the Petersburg that history left behind in 1913. Through this creative act of memory the poetry redeems and saves that history. In the opening dedication Akhmatova writes,

Poem without a Hero,

which she had started writing in 1940. Isaiah Berlin, to whom she read the poem at the Fountain House in 1945, described it as a ‘kind of final memorial to her life as a poet and the past of the city - St Petersburg - which was part of her being’.

211

The poem conjures up, in the form of a carnival procession of masked characters which appears before the author at the Fountain House, a whole generation of vanished friends and figures from the Petersburg that history left behind in 1913. Through this creative act of memory the poetry redeems and saves that history. In the opening dedication Akhmatova writes,

… and because I don’t have enough paper, I am writing on your first draft.

212

*

212

*

* Akhmatova informed several friends that the first dedication was to Mandelstam. When Nadezhda Mandelstam initially heard her read the poem and asked her to whom the dedication was addressed, Akhmatova replied ‘with some irritation’: ‘Whose first draft do you think I can write on?’ (Mandelstam,

Hope Abandoned,

p. 435).

Hope Abandoned,

p. 435).

The poem is full of literary references, over which countless scholars have puzzled, but its essence, as suggested by the dedication, is foretold by Mandelstam in a prayer-like poem which Akhmatova quotes as an epigraph to the third chapter of her own poem.

We shall meet again in Petersburg

as though we had interred the sun in it

and shall pronounce for the first time

that blessed, senseless word.

In the black velvet of the Soviet night,

in the velvet of the universal void

the familiar eyes of blessed women sing

and still the deathless flowers bloom.

213

213

Akhmatova’s

Poem

is a requiem for those who died in Leningrad. That remembrance is a sacred act, in some sense an answer to Mandelstam’s prayer. But the poem is a resurrection song as well - a literal incarnation of the spiritual values that allowed the people of that city to endure the Soviet night and meet again in Petersburg.

Poem

is a requiem for those who died in Leningrad. That remembrance is a sacred act, in some sense an answer to Mandelstam’s prayer. But the poem is a resurrection song as well - a literal incarnation of the spiritual values that allowed the people of that city to endure the Soviet night and meet again in Petersburg.

Akhmatova died peacefully in a convalescent home in Moscow on 5 March 1966. Her body was taken to the morgue of the former Sheremetev Alms House, founded in the memory of Praskovya, where she was protected by the same motto that overlooked the gates of the Fountain House:

‘Deus conservat omnia’.

Thousands of people turned out for her funeral in Leningrad. The baroque church of St Nicholas spilled its dense throng out on to the streets, where a mournful silence was religiously maintained throughout the requiem. The people of a city had come to pay their last respects to a citizen whose poetry had spoken for them at a time when no one else could speak. Akhmatova had been with her people then: ‘There, where my people, unfortunately, were.’ Now they were with her. As the cortege passed through Petersburg on its way to the Komarovo cemetery, it paused before the Fountain House, so that she could say a last farewell.

‘Deus conservat omnia’.

Thousands of people turned out for her funeral in Leningrad. The baroque church of St Nicholas spilled its dense throng out on to the streets, where a mournful silence was religiously maintained throughout the requiem. The people of a city had come to pay their last respects to a citizen whose poetry had spoken for them at a time when no one else could speak. Akhmatova had been with her people then: ‘There, where my people, unfortunately, were.’ Now they were with her. As the cortege passed through Petersburg on its way to the Komarovo cemetery, it paused before the Fountain House, so that she could say a last farewell.

8

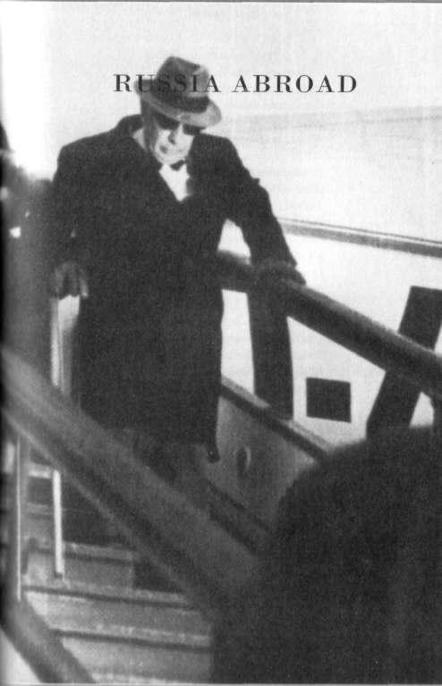

overleaf:

Igor and Vera

Stravinsky arriving at Sheremetevo Airport in Moscow,

Stravinsky arriving at Sheremetevo Airport in Moscow,

21 September 1962

1

Homesickness! that long Exposed weariness! It’s all the same to me now Where I am altogether lonely

Or what stones I wander over Home with a shopping bag to A house that is no more mine Than a hospital or a barracks.

It’s all the same to me, a captive Lion - what faces I move through Bristling, or what human crowd will Cast me out as it must -

Into myself, into my separate internal World, a Kamchatka bear without ice. Where I fail to fit in (and I’m not trying) or Where I’m humiliated it’s all the same.

And I won’t be seduced by the thought of My native language, its milky call. How can it matter in what tongue I Am misunderstood by whomever I meet

(Or by what readers, swallowing Newsprint, squeezing for gossip?) They all belong to the twentieth Century, and I am before time,

Stunned, like a log left

Behind from an avenue of trees.

People are all the same to me, everything

Is the same, and it may be that the most

Indifferent of all are those

Signs and tokens which once were

Native but the dates have been

Rubbed out: the soul was born somewhere,

But my country has taken so little care Of me that even the sharpest spy could Go over my whole spirit and would Detect no birthmark there!

Houses are alien, churches are empty Everything is the same: But if by the side of the path a Bush arises, especially

a rowanberry…’

The rowanberry tree stirred up painful memories for the exiled poet Marina Tsvetaeva. It was a reminder of her long-lost childhood in Russia and the one native ‘birthmark’ that she could neither disguise nor bury underneath these lines of feigned indifference to her native land. From her first attempts at verse, Tsvetaeva adopted the rowanberry tree as a symbol of her solitude:

The red mound of a rowanberry kindled, Its leaves fell, and I was born.

2

2

From such associations the homesick exile constitutes a homeland in his mind. Nostalgia is a longing for particularities, not some devotion to an abstract fatherland. For Nabokov, ‘Russia’ was contained in his dreams of childhood summers on the family estate: mushroom-hunting in the woods, catching butterflies, the sound of creaking snow. For Stravinsky it was the sounds of Petersburg which he also recalled from his boyhood: the hoofs and cart wheels on the cobblestones, the cries of the street vendors, the bells of the St Nicholas Church, and the buzz of the Marinsky Theatre where his musical persona was first formed. Tsvetaeva’s

‘Russia’, meanwhile, was conjured up by the mental image

‘Russia’, meanwhile, was conjured up by the mental image

Other books

Trouble In Spades by Heather Webber

Gator A-Go-Go by Tim Dorsey

Heaven Is High by Kate Wilhelm

His Lordships Daughter by de'Ville, Brian A, Vaughan, Stewart

La esfinge de los hielos by Julio Verne

Love Finds a Way by Wanda E. Brunstetter

Daisies in the Canyon by Brown, Carolyn

The Deadly Nightshade by Justine Ashford

Bloodthirst by J.M. Dillard