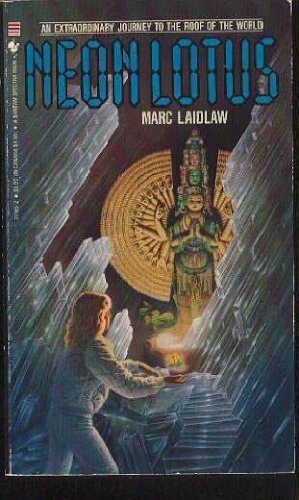

Neon Lotus

Authors: Marc Laidlaw

NEON LOTUS

by Marc Laidlaw

Freestyle Press

“Write like

yourself, only more so.”

marclaidlaw.com

ISBN:

978-1-5323-1076-8

This

ebook edition published in 2016 by Marc Laidlaw

Copyright

©

1998 by Marc Laidlaw

First U.S. edition published by Bantam

Books in 1998

All rights reserved, including

without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in

any form or by any means, including information storage and retrieval systems,

whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented. If you

would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes),

prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the author at

marclaidlaw.com.

This ebook is protected by U.S. and

international copyright laws, which provide severe civil and criminal penalties

for the unauthorized duplication of copyrighted material. Please do not make

illegal copies of this book. If you obtained this book without purchasing it

from an authorized retailer, please go and purchase it from a legitimate source

now and delete this copy. Understand that if you obtained this book from a

fileshare, it was copied illegally, and if you purchased it from an online

auction site, you bought it from a crook who cheated you and the author.

The characters and events in this

book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is

coincidental and not intended by the author.

Cover design

©

2016 by Nicolas Huck (

www.huckworks.com

).

Photocollage created by

Marc Laidlaw based on a photograph by Daniel Winkler (

www.mushroaming.com

), used by permission of Daniel Winkler.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

6. Prayers at a Two-Way Shrine

13. The Opening of the Wisdom Eye

This book is for

my grandfather,

Alexander Zavala

The monks of

Nechung Monastery had wrapped the Medium of the State Oracle of Tibet in over a

hundred pounds of clothing and jeweled armor. The tiny monk could hardly stand

without assistance. He wore white leather boots with curling toes; silken

scarves of red, yellow, and gold, including flags that swayed over his head and

coursed down his back on flexible poles; thick flaring pants of scarlet, and

immensely padded sleeves embroidered with fierce protective eyes. There was

hardly enough of him to fill the spectacular garment; it hung from him in

gorgeous wrinkles. A mirrored breastplate set with turquoise and amethyst rose

and fell unevenly with each ragged breath. At his waist was a sword in a silver

scabbard that dragged upon the floor; on one shoulder, a quiver full of arrows.

An archer’s golden thimble capped his right thumb. His shaven head looked like

a small brown nut, misplaced in so much richness.

As

attendants helped him into the Central Cathedral, the monks in the hall began

to chant with renewed energy.

“Come, Dorje Drakden

,

bearing council.

Come

,

Spirit Minister

,

bringing sage advice

.

Protector of Buddhism

,

we call you.”

Hearing the

chants, the Medium’s eyes rolled back into his head. He staggered beneath the

weight of the ceremonial garb. A young monk hurried to put a low stool under

him. Two others brought forth a massive tiered helmet of gold-plated iron

decked with peacock feathers, bear fur, bells, and grinning golden skulls

weighing more than fifty pounds.

The Medium’s

breath came in rapid gasps. His eyelids fluttered as if he were dreaming. The

monks slipped the helmet onto his head and fastened it beneath his chin with

elaborate slip-knots.

Trumpets

wailed as the monks droned on. The little Medium looked utterly crushed,

overwhelmed beneath garments that weighed more than he. For an instant, slumped

into the Oracular vestments, he seemed to vanish altogether.

Then the

helmet rose steadily upright, lively eyes flashing out from beneath the row of

golden skulls. The ritual garments began to swell, straining against the belts

and ties with which they had been fastened; within seconds they seemed

incapable of containing the powerful body of the Medium.

He was a

common monk no longer.

Dorje

Drakden had arrived.

His first

shout shattered the monotony of chanting. The Oracle’s aides stepped back as he

leapt to his feet. The monks and state officials lining the walls of the

cathedral fell silent and perfectly still, except for those engaged in

invocation and prayers of praise.

The State

Oracle leapt onto his toes, launching into a spinning, capering dance. His

steps were as light and graceful as those of a naked dancer, a swirl of colored

scarves, an illusion.

A brass gong

moaned among the columns of the cathedral, sounding like the sea that had once

drowned these mountains. Five-metal bells sang of space and silence—those

other deeper seas that would never recede.

The

prophetic warrior whirled toward the far end of the hall, where three neon

Sanskrit syllables glowed above the head of an enormous golden Buddha.

OM

AH

HUM

Diamond

white

OM

, ruby red

AH

, and turquoise blue

HUM.

The brilliant characters shone in Dorje Drakden’s eyes. He sent

the body of his Medium soaring aloft in great bounds that the little man could

scarcely have performed even in his ordinary robes.

At the foot

of the giant Buddha sat a figure equally still, equally golden, but no bigger

than a man. Its features were cunningly painted so that it seemed to be alive.

The eyes were like white almonds; the full, smiling lips were red as roses. On

the bridge of the golden nose sat a pair of black horn-rimmed glasses.

Dorje

Drakden bowed before this, the gilded mummy of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. From

a monk waiting beside the jeweled throne, he took a white scarf and draped it

over the mummy’s upraised golden hand. Tears welled from the eyes of the

Protector.

Suddenly,

seizing handfuls of rolled scarves from the monk’s bowl, he began rushing about

to the wail of horns and the clash of cymbals, tossing scarves in all

directions till the air of the cathedral seemed full of streaming clouds.

Scarves settled in the hands of precious images, in the lap of the giant

Buddha, and one mysteriously draped itself around the neck of an elderly

onlooker named Tashi Drogon.

Tashi

touched the white scarf tenderly, as if he had never felt silk before, and

looked over into the amazed eyes of his younger companion, Reting Norbu.

The

Protector danced on.

Tashi noted

the startled expressions of the four Kashag ministers seated along the opposite

wall. The entire Council of Ministers was staring at him, oblivious to the

energetic careening of the Spirit Minister. The prime minister alone kept his

eyes on the dance, although he had certainly noticed the unusual blessing.

Still

stroking the scarf, Tashi returned his attention to Dorje Drakden, hoping that

some explanation might accompany the prophecies.

At last the

dancer slowed his pace. Returning to the mummified Dalai Lama, he dropped onto

his knee and bowed forward. Golden bells sang in the helmet as he dropped his

heavy head.

Venerable

Tara, the oracular secretary sitting to one side of the mummy, extended a

quivering hand to the Oracle, offering a slip of paper folded into a triangle.

Dorje Drakden accepted three such triangles, one after another, and slipped

them under the brim of his helmet. Then he stood stroking the golden hand of

the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, weeping softly. Tashi felt an inexpressible sadness.

The Protector mourned the Dalai Lama as if he were a child who had died only

yesterday, rather than a man who had lived a long life two centuries ago.

As if

realizing the foolishness of despair, the Spirit Minister reared back and broke

into ecstatic laughter—a high-pitched ululation that gradually quieted to a

rapid stream of lilting Tibetan.

There was

not a head in the cathedral that did not lean closer, hoping to catch some part

of the prophecy. But Dorje Drakden spoke solely for the ear of the mummy, and

indirectly to the Venerable Tara who transcribed every word on an electronic

slate. While the words themselves were audible only to the secretary, the music

of the utterances was dear to all. Hearing the Spirit Minister speak was like

listening to a mountain stream, each syllable a drop of rushing diamond-bright

liquid.

As the songs

of prophecy came to an end, Dorje Drakden reached into a bowlful of barley at

the foot of the throne and began hurling handfuls of grain across the wide

chamber. As these blessings came showering down, the Spirit Minister stumbled

away from the Dalai Lama’s throne. His body seemed to deflate. The robes fell

loose again, releasing the Protector. The face beneath the helmet turned red,

then purple, and finally blue.

Attendants

rushed forward and caught the Medium as he fell. They slipped the knots beneath

his chin before the helmet strangled him. One took the helmet with a gasp at

its weight; two others lifted the hugely padded body of the unconscious monk

and bore him away.

Reting Norbu

squeezed Tashi’s arm. “You’ve been honored.”

Tashi

nodded, hardly believing what had happened. “It does seem auspicious,” he

admitted.

The trumpets

shrieked their most deafening blasts in conclusion and the monks, after

prostrating themselves in the direction of the Dalai Lama’s mummy, began to

move out in files.

Across the

room, the four ministers of the Kashag uncrossed their legs and rose from the

cushioned platform. The prime minister who had sat above them greeted the

Venerable Tara and accepted the slate containing the prophecies. The Kashag

crowded around but he held up a hand to forestall them.

“We will

convene in one hour,” he said.

The

ministers hurried toward the doors, barley crunching underfoot.

The prime

minister fixed his eyes on Tashi Drogon and came striding toward him. He wore a

plain khaki chuba with the sleeves folded back to show that despite his

position he worked with his own hands. The Silon was famous for trusting none

but himself with sensitive tasks.

“Doctors,

you will be present for the reading, of course?”

“Certainly,

Silon,” Tashi said.

“Am I

permitted?” asked Reting.

“As Dr. Drogon’s

student and collaborator, I assume he will want you to witness the answer to

his question.’

“Reting is

more than my student,” said Tashi. “He is my partner.”

Reting bowed

to each of them. “Thank you.”

The prime

minister’s eyes lingered on the scarf that hung around Tashi’s neck. “Have you

any idea what it means?” he asked in a low voice.

Tashi

shrugged. “No, Silon. Except perhaps that our device has divine approval.”

The prime

minister nodded and granted Tashi a rare smile. “My own thought as well. The

prophecies may explain further.” He bowed to both doctors then went after the

departing ministers. Two guards accompanied him, keeping their eyes on the electronic

slate.

Several

muscular monks watched from between the columns, waiting to see if the doctors

would leave on their own. Tashi looped the scarf around his neck so that the

wind would not blow it away, then he and Reting went outside.

A chill wind

greeted them, coming down from the Dhauladhur range of the Punjabi Himalayas.

He smelled the faint sweetness of rhododendron and also the metallic tang of

snow on granite. He slid his finger along the seal of his insulated jacket, a

tattered but beloved garment he had purchased when he was a student in America;

he had found it in an astronautics surplus store. The jacket, he sometimes

joked, was nearly as old as Reting and had withstood the trial of time with

considerably less wear.

Although a

young man, Reting Norbu was forever stricken by colds and gastric complaints.

His teeth were bad and his face preternaturally thin. He had suffered great

deprivation in his childhood; and later, given the chance of improving his lot,

he had forsaken food for textbooks and sleep for study. The dark circles

beneath his eyes were permanent, as was his doleful disposition.

“Cheer up,

Norbu,” was Tashi’s frequent exhortation, although little was the good that it

did. He repeated it now. “Things look promising for us,” he added.

“I don’t

know,” said Reting. “When the Kashag gets ahold of a thing, I fear for it. They

pull it in four directions at once, till there’s nothing left but tatters.”

“The Silon

will hold them steady. He’s a good man. He understands our purpose as well as

our needs.”

“I don’t

know. I hope you’re right, of course.”

Tashi thrust his hands deep

into the pockets of his jacket, “Besides, they can’t do a thing without our

cooperation. Unless we can get the Bardo device to work, all their schemes and

plans for it mean nothing.”

“Do you

think it will ever work?”

“Let’s see

what the gods say, shall we?”

Reting

seemed on the verge of some pronouncement gloomier than his preceeding ones;

but whatever it might have been, a violent sneeze diverted him.

“You’ve got

a cold coming on, Reting.”

“It’s

nothing.”

“Take care

of yourself, my friend!”

“I swear

it’s . . . ”

Tashi

unlooped the Oracle’s scarf and wrapped it around Reting’s neck. “Come, let’s

get some tea. We have time.”

In a small

cafe near Dharamsala’s main square, in the shadow of the Namgyalma chorten,

they sat sipping salty buttered tea until the sweat sprang out on their brows.

Reting was not inclined to speak so Tashi watched the traffic in the street.

Locals and pilgrims alike circumambulated a stand of prayer wheels below the

chorten, dragging their hands over the copper barrels as they muttered mantras.

Merchants crouched against a low wall at the foot of the shrine, selling grain

and vegetables from flat circular baskets. One could almost believe that this

was Tibet. Undoubtedly life had gone on like this in Lhasa before the Chinese

occupation. The exiled Tibetans carried on as they had for ages, as if their

homeland were forgotten.