New Moon

Authors: Richard Grossinger

Tags: #BIO026000 Biography & Autobiography / Personal Memoirs

B

LURBS

AND

REVIEWS

OF

THE

1996

PRECURSOR

TEXT

TO

New Moon: A Coming of Age Tale

“At once a memoir, an account of psychoanalysis, and a both savage and loving account of New York in the ’50s,

New Moon

is a work with many layers and a unique tone, reminiscent of Robert Musil’s

A Man Without Qualities

in its blend of analytical realism, melancholia, and acute psychoanalytic and philosophical penetration.”

—Andrew Harvey, author of

The Divine Feminine: Exploring the Feminine Face of God Throughout the World

“A strange and remarkable self-evaluation in the form of a novel—illuminating, tender, moving, evocative … any number of adjectives of praise would be appropriate.”

—George Plimpton, author of

Out of My League

“A fascinating self-portrait of the youth of one of our most profound and rebellious thinkers, told with a deceptive simplicity that is capable of shifting at any moment into the haunted resonance of a fairy tale, and in a language so nakedly honest it is never more than one step away from tenderness.”

—Gerald Rosen, author of

The Carmen Miranda Memorial Flagpole

“Indeed, some readers are going to rank this memoir of baseball, summer camp, Latin classes, domestic terrors, and enchanted moments at Grossinger’s as a spiritual quest in the tradition of Blake, Emerson, and … James Agee….”

—Mike Harris,

Los Angeles Times

“Richard Grossinger tells me who he is, so he shows me who I am.”

—Joy Manné, author of

Soul Therapy

“… skillfully evokes the world of ’50s New York and Grossinger’s Catskills as well as the counterculture of the ’60s….”

—

Publishers Weekly

“

New Moon

is something new under the sun, a real psychoanalytic autobiography.”

—

Psychoanalytic Books: A Quarterly Journal of Reviews

—A Coming-of-Age Tale—

Richard Grossinger

North Atlantic Books

Berkeley, California

Copyright © 1996, 2011, 2016 by Richard Grossinger. All rights reserved. No portion of this book, except for brief review, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the written permission of the publisher. For information contact North Atlantic Books.

Published by

North Atlantic Books

Berkeley, California

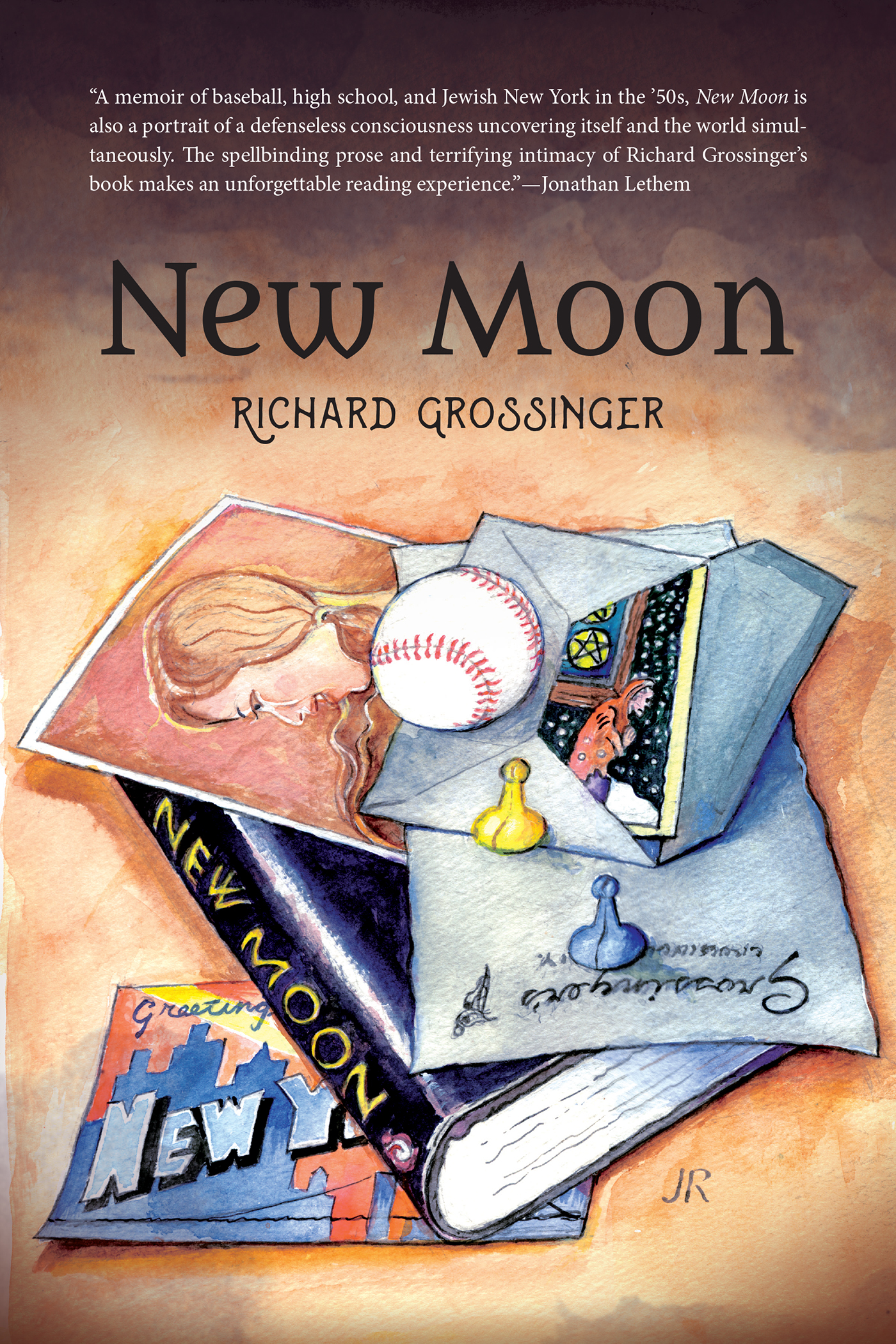

Cover art by James Rauchman

Cover

design by Jasmine Hromjak

New Moon: A Coming-of-Age Tale,

is sponsored and published by the Society for the Study of Native Arts and Sciences (dba North Atlantic Books), an educational nonprofit based in Berkeley, California, that collaborates with partners to develop cross-cultural perspectives, nurture holistic views of art, science, the humanities, and healing, and seed personal and global transformation by publishing work on the relationship of body, spirit, and nature.

North Atlantic Books’ publications are available through most bookstores. For further information, visit our website at

www.northatlanticbooks.com

or call 800-733-3000.

The Library of Congress has catalogued the first edition as follows:

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Grossinger, Richard, 1944–

New moon : a memoir / Richard Grossinger.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978–1–58394–985–6

ISBN 1–883319–44–7

ISBN (ebook) 978-1-62317-097-4

1. Grossinger, Richard, 1944– —Homes and haunts—New York (N.Y.) 2. Authors, American—20th century—Family relationships. 3. Grossinger, Richard, 1944– —Childhood and youth. 4. New York (N.Y.)—Social life and customs. 5. Grossinger, Richard, 1944– —Family. 6. Resorts—New York (State)—Ferndale. 7. The Grossinger, Ferndale, N.Y. I. Title.

PS3557.R66Z468 1966

813’.54—dc20 96-2106

CIP

This book is for my daughter Miranda

Dedicated in 1987 when she was thirteen

ONTENTS

Part One: The Child in the City (1944–1956)

Part Two: The Kid from Grossinger’s (1956–1960)

3

Please Don’t Leave the Party Yet

Part Three: Teenager in Love (1960–1962)

Part Four: Initiation (September, 1962–April, 1964)

Part Five: The Ceremony (April, 1964–June, 1965)

Life is as fathomless at its alpha point as in mementos of yesterday. We seem to ourselves much like the universe: originless, sealed by walls of gravity, light, and space-time, or by the innate warp of beingness. Reality is a construct, but of what? We matriculate from an egg, a chrysalis, on a planet lassoed to a star in a void of inexplicable nature and proportions. Even that is circumstantial. Our existence could be any number of things.

For a place of so much light, for such a glistening, intaglioed husk, this world is a hoax. Only its appearance is bright, its surfaces and subsurfaces. Otherwise, we live among shadows on a darkling plain.

Memories define us because they lie along the thread that recognizes us as ourselves. At the same time, we sense the background of everything we

don’t

remember and in most cases never experienced, which is many times greater and constitutes the fabric of existence.

I can even vaguely remember a time before any of this existed or had to exist.

We fall too against a screen which, although no longer explicitly astrological and feudal, is just as hierarchic and zodiacal.

Other than a thread spun by heart-lung machines, time is timeless: we are inoculated, like a ghost through a cone, into a mirage. There everything seems to take hours, days, decades; in fact, it’s over in a blink: an instantaneity experienced as an eternity. An aquatic mayfly enjoys thirty exquisite minutes in a pond, a creosote bush converts sunlight in a desert for 11,000 years—these are at par. However many times a creature falls asleep and wakes, it lives but a single day, a Great Day rotating about a Great Sun.

As we age, the dot of location erodes. Prior decades fission, wrapping around each other like waterbugs on decaying insects.

Each moment is already eternal. Each moment reverberates forever. Each moment is already obliterated.

T

HE

B

EGINNING

O

F

T

IME

My oldest memory is of seeing an Easter egg in a bush where branches met at the trunk. I had already found that one, but the man had rehidden it.

I came back clutching it as he laughed.

That chalky blue is anterior to my life. I can touch it still, radiant and unscathed.

But who was that man? Where was there a yard with such a bush?

On the first morning of time Nanny stood in the alcove, grinding oranges. She poured them into a glass decorated with flowers. Orange flooded my mind.

I crawled on a carpet among stuffed chairs. At its end stood bureaus with ivory figurines, flat goblets of colored oil. Golden frames held etchings of long-whiskered dancing men. There I played with rubber farm animals, stuffed clowns and donkey dolls, metal buses, and pearly white schmooes, one inside another inside another. Yarn of treasure balls unravelled into trinkets of tiny plastic airplanes and jeweled rings. My mind was a quandary of voices. I was no one in particular. The adults kept saying,

“Open the door … Riiich-ard!”

Photographs of the time show sedans on streets, people in shaggy coats. I can’t believe I was young so long ago. Those were the Christmas trees and frosted bulbs of the 1940s. Every toy was a rough amulet, every button, colored thread, and bundled sweet an art and craft. Snow was a wild thing.

Nanny slept in a corner of my room. She dressed me, made my food, put me down for nap, bathed me. She was a witch who loved me but a witch all the same.

In the afternoon I lay in my crib, waiting for her to come fetch me. I explored the contours of my chest and legs. Knees, feet, and elbows thrashed, snagged at sheets.

Along the crack between ceiling and wall I glimpsed the portal, the juncture between life and everything else. I still see that line: the same mis-assignment of coordinates, the same impervious crevice to another couloir. String theory approaches the possibility: universes tucked inside fibers, one in another in another. A child feels only enormity, immanence, danger.

I chased my balls in their lining. I rubbed sore the light in my eyes.

The animals on my quilt were loyal—Zebra and Tiger and Bear. My hands underneath moved them. I caused them to tussle, then make nice, as I tossed up the covers around me, pressing them into each other in friendship, until I rolled into sleep.

… awoke babbling … the room drained to purple, the opera singer practicing in the courtyard, her trills echoing throughout my mind.

I imagined her later as the lady on the cover of a record whose name began with the impossible letters “Xt….,” a songstress with hands held upward as if trying to stop something horrible from happening—gold shells on her forehead and dangling from her face and body, eyes staring blindly outward; a stone god breathing on her from above, another behind her. (“Voice of Xtaby” was the Capital Release of Peruvian soprano Yma Sumac, made famous by her vocal range. But throughout Mesoamerica “Xtaby” meant “Female Ensnarer,” a demon who seduced and killed.)

After nap I helped Nanny make dinner, pulling limas from their spongy shells, plunking the beans into a pot, delighting in the pings. Scent of turnips, carrots, and pot roast enveloped the kitchen.

After dinner, after playtime Nanny cuddled me in bed. Then I slipped into my own shadows. Then another morning began another day.

Daddy wore brown suits and beat-up felt hats, smoked a cigarette and chanted in Hebrew,

Anakhnu modim ….”

and

“Shama Yisra-el.”

He also sang,

“Old Man River, that Old Man River…. ”

I remember waiting the whole afternoon to see him again, breaking loose of Nanny, who regarded him with suspicion and held me back … running down the hall and throwing my arms around him as he came through the front door. It was the longest I had stayed on my feet without toppling, and I tumbled into his embrace. In great surprise he exclaimed and hoisted me in the air. At least he smelled of other worlds and not our charnel home.

One evening with the help of his taxi man Daddy carried a large box. He unpacked it, pulled off papers and tossed them on the floor. It was a victrola. He took a large black disk from an envelope. He set it on the machine’s spinning platform and lowered a metal arm into sound:

“Oh where have you gone Billy boy, Billy boy?”

Then …

“Cruising down the river / on a Sunday afternoon …”

Those melodies join this world to another; all you need do is change their syllables to a language of Toliman or the Pleiades, which are not so different as you might think.

In retrospect I don’t see (nor did I then) any ordinary river but, from a 45 degree angle, a cobblestone canal, its banks swarming with adults at carnival. Through a gap in notes of the song swims a giant turtle.

Billy emerged from the mists of a bog forest, suspenders holding up his farmer’s pants:

“Oh where have you gone, charming Billy?”

In the minor chord between “charming” and “Billy” lay a blankness, a hiatus where hearts beat but minds could not go.

“It was a horrible experience,” my mother recounted. “It almost killed me. You were black and blue. I was covered with blood. He used forceps.” The word itself conjured implacable machinery, as if the doctor had plied a pillory and heretic’s fork to get me out of her. “You were screaming so—I thought you were dying.”

That was

her

story. I have had (all my life) a recurrent dream: an elevator in a hospital, very old, long ago. Unseen, I visit her in her room and wait, expectant in darkness as in a theater. (In later years

my wife is there instead, about to have our son. These epochal events merge and I am witness to both as one.)

I have no name for this dream; it is just “the feeling.” Words give pale approximations: “homesick” …

“déjà vu”

… “alien” … “acrid.” The sense of premonition is inescapable: footsteps approaching … I feel I cannot prevent calamity.

And yet I have waited beyond time for this being’s appearance, long after my children were born and had grown into adults.

Even now I wander in a labyrinth of births of children and old men dying.

At other times I have discovered, in that same room, a jungle of orchids, a fountain bursting through the floor, exotic species of water blossoms and long-extinct sea animals quivering in shells—in short, an interstellar laboratory.

I have dreamed that it was not my mother in the room at all. A replica lay in bed in her place, just as tall as her, just as red lips and black hair. She had Martha’s appearance and gestures. She spoke exactly as my mother spoke. She knew everything about me my mother did.

Then a doctor came from nowhere and attacked me with his knife. I felt his hard, grimy body, stinking of medicines. I fought him off but awoke with the scar of his strike just above my Adam’s apple. And glimpses of a fleeing intruder.

Other times I cannot find my mother’s room, so keep returning to crowded elevators; I take them up higher and higher, hundreds of storeys through decorated corridors and ballrooms, each filled with weddings and celebrations.

Our apartment was at 1220 Park Avenue on the corner of 95th, a block before the train shot out of the ground, turning the landscape squalid. Buildings became blackened caves. On our side of 96th doormen guarded entrances to castles that grew more magnificent and fancier as they progressed downtown.

Sometimes wind along the Avenue rattled our windows behind closed drapes, but never so fiercely as during the hurricane. Mommy was giddy in preparation, making phone calls, ordering food, warning me to keep back from the glass.

Sky blackened. Rain splattered the pavement. Daddy put on an overcoat and scarf, the door slamming behind him. He ran down the street to pick up groceries. As he worked his way back he held onto lampposts to keep from being blown away.

Despite Mommy’s admonitions, I peeked. I saw a man stuck at the corner, his umbrella turned inside out. Sheets of paper danced through air; boreal spirits rapped harder and harder on the glass, but it didn’t break.

I kept to the center of the room, filling my scrapbook with cars and trucks from magazines, cutting around tires and bumpers and sticking them two to a page from a jar of white glue.

Mommy was a perfume demon with dark piercing eyes. At bedtime I pulled back from her Noxzema kisses, but she grabbed me, forcing affection, eyes trapping, red nails sharp on my arms till I made a kiss back. “Don’t you love me?” she insisted.

How could I not?

I took her hand down 96th Street. In an indoor garden, orchid mist scented the air. It was a fairy tale: many-colored blossoms, fragrant dew. She commanded the proprietor in a strong but persuasive voice until he brought single blooms from his refrigerator. These he tied in a bunch and wrapped in colored tissue. At home she arranged them with brusque hands in a purple (almost black) vase.

Sometimes Mommy screamed, pounded at walls, and ran from room to room. I heard her whimpers, doors slamming, then muffled sobs. Daddy tried to cajole her, but his appeals brought only ghostlike howls.

She shrieked a demonic word. “Don’t get hysterical, Martha,” he pleaded.

Cancer wasn’t just a malignancy, a monster that turned you into a cadaver; the very sound of it released dreaded meanings. When I learned to read, I found it secretly lurking behind “candy” and “canary” and “Canada” until I could see the rest of their letters.

Dr. Hitzig was called—a fat goblin in a black suit. In her nightclothes Mommy ran down the hall to meet him. With a magisterial hand he patted her shoulders and settled her shudders. “You don’t

have anything,” he said, “but an unstable constitution and an overactive imagination.” He turned to Daddy, “Codliver oil and honey. No heavy meals. Four times a week chicken soup.”

It wasn’t death we feared but a spookier thing that went by its name. What made it so horrible was that no one knew what it was, when it was coming, or what would happen to us when it did. We were on constant alert.

Mommy knew that we were in danger. She sniffed stuff in cans and jars for venoms meant to get us. She found fungus on marmalade, though it was a fleck of butter from the knife. She kept scrubbing tabletops, sinks, toilet seats. Everything was suspect, ripening with something else.

Most people were our enemies. It didn’t matter that we pretended to like them. Even Dr. Hitzig was bad.

I was playing submarine in my bath when dark rust spurted out its seams. I could feel the contamination spreading, touching me. I pushed it away and leaped from the tub. I ran naked down the hall. Nanny caught me, wrapped me in towels, held me till my shaking stopped.

One morning Mommy was gone. She stayed away a long time. Nanny told me she would return with a baby. When I realized another of us was coming I saved a favorite stuffed animal, a bear for him, and was hurt that he didn’t take it from me when I held it up as he was rushed past in his blanket. His name was Jonathan; he was placed on the other side of my room, a china bug whimpering and bawling.

Everything was proceeding according to plan.

I planned to hide this brother behind a chair, teach him my words, and surprise everyone with a talking baby at dinner.

Pushing the carriage with my brother, Nanny took me to the playground. I mastered the little slide and gradually got up courage for the big one. I climbed the stairs and sat at the top. A line of kids collected behind me. They shouted Go! I flew down the chute. I came to my feet and ran into Nanny’s arms.

She put me in the sandbox, telling me to be careful of other kids’ peeing. I rolled in granules, pressing my cheeks against the moist

fuzziness. They were a cake, not quite baking. I dug marbles out of dirt, tiny planets emblazoned with smoke. I was burrowing with my nails, making a cave-world when Nanny stood me up and brushed me off.

We walked through the park. I followed squirrels stopping and starting along the bushes, running up and down bark. When I saw the wagon man, I begged Nanny to buy nuts. She agreed, as long as I didn’t sneak any for myself. “Peanuts are poison,” she said.

A sweet odor rose from a small heated bag, elephants drawn on its sides, top pleated and tucked. Unwrapping its folds, I tiptoed through the grove, coaxing fluffytails from afar, tossing a treat at a time as they took the shells in their paws, transferred them to their mouths, scooted away to eat or bury them. I would hold different squirrels in my mind, tracking their progress, regretting their departure if they hadn’t gotten any. When the bag was empty I tried without success to get them interested in spiny brown balls that lay under trees. Then Nanny summoned me on.

As we passed the Museum, I wandered in a garden of white stones, hundreds of smooth ones all around, an unguarded treasure. Clouds roared overhead like pirate ships. Mica sparkled silver. A witch in a black coat spread bread and corn pellets from her purse, yellow and orange gems, crumbs and bits of old rolls. Pigeons flocked, so many wings she seemed to be growing them from her coat. I tugged on Nanny to go.

We walked along Madison. Its streets were filled with characters, their perfumes mingling with vapors of shops, fruits and vegetables set on boxes, air conditioners dripping, hot grills blown by fans. Each store had its signature—a bubblegum of toys, a frosty cavern of roses, a cookie circus with amulets of sparkling sugar and chocolate rings, a restaurant puffing charcoal from a grate.

Nanny asked my help in pressing Jonathan’s carriage up the steps through the door. I hurried to be good.

I used to get lost. These episodes have a quality of wandering beyond the world. In the original such adventure I strayed from Nanny,

who was reading a book as her foot rocked the carriage, to a spot I later recognized as 99th Street by Fifth Avenue. As I proceeded in my trance, I was astonished suddenly to find the sidewalk rippled. I had assumed all pavement was smooth.

I came to an atrium of tulips about a silver orb, the reflection of a child passing through an asterisk of light. Flowers stretched above me like trees.