New York at War (9 page)

Authors: Steven H. Jaffe

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #United States

Baxter and Maverick were preaching to the converted. A militantly anti-Dutch coterie of courtiers and soldiers had formed around James Stuart, Duke of York, Lord High Admiral, and the king’s younger brother—and the Earl of Clarendon’s son-in-law. James reserved his special hatred for the WIC, which had found a compelling source of profit in the African slave trade—the very traffic that James’s own Royal Company of Adventurers was bent on monopolizing. The duke’s animus against the Dutch was further fueled by Sir George Downing, president of the Council of Trade, and by Downing’s cousin John Winthrop Jr., who happened to be governor of Connecticut. In 1661 Winthrop had arrived in London with a meticulous description of Fort Amsterdam’s defenses. Ironically, Stuyvesant and Winthrop had sustained a courteous correspondence for years, and when political complications made it awkward for the Connecticut governor to sail to England from the neighboring colony of New Haven, Stuyvesant obliged him by letting him embark from Manhattan. Winthrop took advantage of the sight-seeing opportunity on behalf of his king.

19

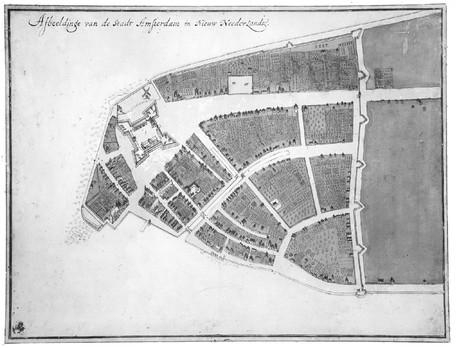

A bird’s eye view of New Amsterdam about 1660, showing Fort Amsterdam (upper left) and the wall along the city’s northern boundary, today’s Wall Street (right). Jacques Cortelyou,

Afbeeldinge van de Stadt Amsterdam in Nieuw Neederlandt

(the Castello Plan), c. 1660. COURTESY OF THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY,

WWW.NYPL.ORG

.

Like Cromwell before them, royal bureaucrats pored over maps showing a North American coast that appeared solidly English from the borderlands of Spanish Florida to the frontier of French Canada—solidly English, that is, except for the irritant called New Netherland. On March 22, 1664, Charles II bestowed on his brother James a gift consisting of the territory stretching between the Delaware and Connecticut Rivers—in essence, New Netherland. The king also lent James four warships, 150 sailors, and 300 soldiers in order to secure his gift. By May, the Duke of York’s expedition was ready to embark from Portsmouth.

20

Joining the English attack force were Samuel Maverick and James’s hand-picked commander, Richard Nicolls. The duke couldn’t have chosen a better leader for the mission. Forty-year-old Colonel Nicolls came with impeccable royalist credentials. A close friend of the duke’s, Nicolls had commanded cavalry during the English Civil War and then followed the royal family into exile on the continent during the years of the Commonwealth. In an age when soldiers routinely viewed arson, pillage, rape, and murder as first rather than last resorts, Nicolls possessed something extra—patience, a taste for diplomacy, perhaps even empathy for the predicament of his adversaries. He grasped the weakness of the Dutch position in North America, but also the folly of overkill, of needlessly bludgeoning the enemy into submission if persuasion might work just as well.

To storm the port of New Amsterdam, battering it with cannon fire or burning it to the ground, would serve nobody, Nicolls reasoned—certainly not the duke, nor the merchants and Westminster dignitaries dreaming of fur-laden ships sailing up the Thames. And by harming and humiliating the Dutch colonists, it might buy years of trouble. Annihilation as a threat, as a lever to compel negotiation, only to be unleashed as a last resort: this was the card Nicolls intended to play once he reached Manhattan Island. The one variable he didn’t include in his reasonable equation was Peter Stuyvesant.

On August 26, 1664, “four great men-of-war, or frigates, well manned with sailors and soldiers” and bristling with a total of ninety-three cannon, arrived in New Netherland. The vessels anchored off Gravesend, just beyond the Narrows separating Long Island and Staten Island. Nicolls’s soldiers disembarked and marched through Long Island farmland to occupy the ferry landing at the small village of Breuckelen (Brooklyn), which hugged the East River shore opposite New Amsterdam (at the modern site of the Brooklyn Bridge ramp and anchorage). “In his Majesty’s name I do demand the town, situate upon the Island commonly known by the name of Manhatoes with all the forts thereunto belonging,” Nicolls told the delegation sent by Stuyvesant to demand an explanation.

The arrival of the vessels, and the presence of hundreds of English soldiers brandishing muskets and pikes on the Breuckelen shore, sent the citizens of New Amsterdam into a panic. Anxiety had been building since early July, when rumors of an impending invasion had arrived. The English were bent on seizing the colony, reported the Reverend Samuel Drisius, one of the town’s leading Dutch clergymen: “if this could not be done in an amicable way, they were to attack the place, and everything was to be thrown open for the English soldiers to plunder, rob and pillage.”

21

Nicolls, Maverick, and their comrades in arms had been busy setting their plan in motion. Arriving first in Boston in late July, Nicolls had demanded that Massachusetts march its troops overland to participate in the assault on New Amsterdam, but he found the Puritan leaders as loath to move as they had been when importuned by Cromwell’s agents a decade earlier. Instead, Nicolls turned to Governor Winthrop of Connecticut, who agreed to “beat the drum” to rouse the English settlers of Long Island for the attack on Manhattan. When New Amsterdam’s townspeople peered across the East River at the enemy force on the opposite shore, they saw Long Island farmers (from both sides of the Hartford Treaty line) whose eagerness to end Dutch dominion equaled that of the English soldiers with whom they were rubbing shoulders.

22

Peter Stuyvesant and the city burgomasters had tried to prepare New Amsterdam, now a town of 1,500 inhabitants, for eventual English attack. They had hired masons to line the fort’s earthen outer walls with stone and to build two imposing, cannon-lined defensive bastions along the ramparts of the wooden wall that guarded the northern approaches to the city. Even more ambitiously, they had finally agreed to collaborate on a project that, when finished, promised to protect New Amsterdam in a familiarly Dutch way: a wall of unbroken wooden palisades completely encircling and enclosing the town. Stuyvesant, paying careful heed to rumors that the Lenape, with English encouragement, were planning to rise once more, had also insisted that the outlying villages of New Haarlem, New Amersfoort, Midwout, and New Utrecht be fortified with palisades and blockhouses. He sent company slaves to help build them.

23

But the perennial problems had surfaced. The loans that Stuyvesant exacted from city merchants—again, after hard bargaining over rights and privileges with the city fathers—never met the financial needs of defense expenditure. The grandiose plan for a wooden wall sealing off the city of New Amsterdam from its foes was never completed; in fact, it was barely begun. Once more Stuyvesant was reduced to futile pleas to Amsterdam for help, signing one of them, “your faithful, forsaken and almost hopeless servant.” The town magistrates added their own request, naively writing to Amsterdam for three or four thousand “good soldiers, one-half with matchlock, the other half with flintlocks.” In response, the company had sent fifty.

24

The condition of the town’s fortifications remained feeble in the days before Nicolls and his men appeared on the Breuckelen shore. Stuyvesant lamented the flimsy state of the wooden wall, periodically weakened by townspeople who tore off planks for firewood. Fort Amsterdam, its walls now braced with stone, was in somewhat better shape. Throughout the summer of 1664, slaves, soldiers, and burghers toiled with “shovels, spade or wheelbarrow” to repair its ramparts and gun carriages. But gunpowder was low, and a mere 180 soldiers, augmented by some 300 civilian militiamen and other townsmen, would face the challenge of defending the wall, the fort, and two riverfronts. Food would be scarce; the autumn grain had been harvested but not yet threshed. Aggravating the food shortage, in mid-August the Dutch vessel

Gideon

had arrived in the East River from the Guinea Coast, carrying 290 slaves ready for sale—each with a desperately hungry mouth to feed. Even in the face of invasion, Stuyvesant was unwilling to starve a human cargo worth so many guilders, whether or not his conscience might have permitted it.

25

But despite the holes in the city’s defenses, Stuyvesant was defiant. On September 1, Nicolls, now ensconced in a Staten Island blockhouse the Dutch had built as a defense against the Lenape, sent a delegation over to Fort Amsterdam bearing a letter advising Stuyvesant that Charles II, “being tender of the effusion of Christian blood,” would guarantee “Estate, Life and Liberty” to every New Netherlander “who shall readily submit to his Government.” Those who did not surrender unconditionally “must expect all the miseries of War.” Lacking other resources, Stuyvesant played for time, insisting that he could not resolve the confrontation before receiving direct orders from the Netherlands. Nicolls’s reply was curt. Stuyvesant had forty-eight hours to surrender New Amsterdam, or his people would face the consequences.

26

Nicolls was calling Stuyvesant’s bluff. Maverick and others in his entourage assured him New Amsterdam should fall like a house of cards when faced with the prospect of assault. The presence of his warships, along with the sight and sound of hundreds of English soldiers clamoring on the Breukelen shore, must have convinced any reasonable man that the only course was to accept generous terms and surrender honorably. But

was

Stuyvesant bluffing?

Nicolls decided to try negotiating one last time. On September 4, as the forty-eight-hour deadline expired, a small boat approached Fort Amsterdam from across the bay. Six emissaries disembarked, among them Governor Winthrop of Connecticut. They brought a letter, once more spelling out peace terms that included freedom of domicile, property, trade, and religion for any Dutchman who laid down his arms. That was the carrot; the stick soon materialized. Two of Nicolls’s warships moved ominously up the bay under full sail and soon faced the fort broadside at the entrance to the East River. So close were the vessels to the populous tip of Manhattan that their cannon muzzles were clearly visible from the shore. Nicolls’s clock was ticking.

Stuyvesant read out the surrender terms to a hastily assembled group of his councilors and city magistrates inside the fort. When the city’s two burgomasters later returned to request a copy of the letter so they could share it with their fellow townsmen, Stuyvesant vehemently refused and ended the scene by ripping Nicolls’s missive to shreds and throwing the pieces to the floor. As angry burghers snatched up the fragments in order to piece the document back together, Stuyvesant knew what the result would be once his townsmen learned its terms. Outgunned, weary of the West India Company’s indifference to their fate, valuing their lives and property above loyalty to a distant homeland, and already acquainted with English ways through contact with their neighbors, New Amsterdam’s people would make an easy choice.

27

With or without the support of his townsmen, Stuyvesant was determined to put up a fight. As Nicolls’s warships loomed at the island’s tip, Stuyvesant mounted the rampart of Fort Amsterdam and instructed a gunner to prepare an artillery barrage against the vessels. As the soldier readied his match to ignite the cannon’s fuse, Johannes Megapolensis and his son Samuel, two of the town’s Calvinist clergymen, clambered up and sought frantically to talk Stuyvesant out of it. The fort had only twenty-four cannon, the two clerics argued, arrayed against the combined fire power of four well-armed warships. The gesture of defiance would be a suicidal one, possibly leading to the deaths of hundreds of helpless townspeople. Stuyvesant listened, told his gunner to stand down, and resignedly descended the parapet in the company of the two relieved ministers.

28

Peter Stuyvesant had toiled hard to prepare his city for war. But his people would not fight. Even worse, New Amsterdam was coming apart at the seams. The wife of a prominent merchant warned her neighbors against trusting the company’s soldiers, for “those lousy dogs want to fight because they have nothing to lose, whereas we have our property here, which we should have to give up.” With English soldiers on the Long Island shore itching for the opportunity to ransack the town, some of the WIC’s resentful, impoverished mercenaries inside Fort Amsterdam decided to beat them to it. One soldier was overheard to gloat that “we know well where booty is to be got and where the young ladies reside who wear chains of gold.” A group of townsmen had to beat back their own soldiers trying to pillage merchant Nicolaes Meyer’s house.

29

On September 5, the day after Stuyvesant had readied his gunner to fire on the invaders, a group of ninety-three townsmen signed a petition pleading with the director to avoid “misery, sorrow, conflagration, the dishonor of women, murder of children in their cradles, and, in a word, the absolute ruin and destruction of about fifteen hundred innocent souls,” lest they be obliged to “call down on your Honor the vengeance of Heaven for all the innocent blood which shall be shed.” One of the signers was Stuyvesant’s seventeen-year-old son, Balthasar. Stuyvesant sent word to Nicolls and had the white flag hoisted over the fort. He was ready to negotiate.

30