Niagara: A History of the Falls (29 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

The results were startling. Even before moving to Niagara Falls, Hall’s Pittsburgh Reduction Company was able to offer aluminum for less than a dollar a pound. In little more than a decade the price would drop to eighteen cents. In a single flash of inspiration, a youth only a year past voting age had given Niagara Falls its first major industry and made the United States the largest aluminum-producing country in the world.

Hard on the heels of Hall came another inventor, the immaculate and methodical Edward Goodrich Acheson, a self-taught chemical wizard who had just discovered how to make silicon carbide, or Carborundum. Next to diamond dust, it was the hardest abrasive known to man. Acheson had been forced to drop out of school at the age of seventeen, but what he lacked in formal training he made up in reading and in enthusiasm. He read everything, from the Alger-inspired

Try Again, or the

Trials and Triumphs of Harry West

to early works on metallurgy. Like Hall, he devoured the

Scientific American

. Edison was his hero; chemistry and electricity were his passions. He was scarcely out of school before he had patented a rock-boring machine for coal mines. That was the first of sixty-nine patents that he would take out in his lifetime. George Westinghouse bought several and thus helped him on his way.

Acheson went to work for Edison at Menlo Park and later in Europe. He saw the need for a new abrasive – diamond dust was horribly expensive – and when at last he set out on his own, he began a series of experiments, hoping to find one. He soon noticed that clay got harder after being impregnated with carbon, and he wondered whether or not a mixture of the two might be fused if subjected to several thousand degrees of heat.

In March 1891, using a small iron crucible, Acheson carried out his experiment, thrusting a carbon rod, connected to a generator, into a mixture of clay (aluminum silicate) and carbon. The results were disappointing; apparently nothing had happened. But Acheson took a second careful look and saw a few bright specks attached to the rod. He stuck one of these on the tip of a pencil and drew it across a pane of glass. To his astonishment and delight, it cut the glass like a diamond.

By 1892, Acheson’s Carborundum Company was making about twenty pounds of the product a day, and the price was dropping. But Acheson realized that if he were to succeed he must make much larger quantities for sale at a much lower price. The abrasive had been selling for $576 a pound – half the price of diamond dust, but still prohibitive. Acheson was determined to bring the price down to

eight cents

a pound. For that he would need substantial amounts of electrical power, and that was available only at Niagara Falls.

Without telling his board, he signed a contract with the Niagara Falls Power Company for one thousand horsepower a day, with an option for a later amount up to ten thousand horsepower. It was a daring move. Acheson was contemplating increasing production by a factor of twenty at a time when his original plant at Monongahela, Pennsylvania, could sell no more than half the Carborundum it produced. No wonder, then, that when he finally told his board, the directors resigned on the spot.

The mass walkout did not faze him. He pressed on, thinking big, planning the largest electric furnace in the world. It was scarcely in operation before he made a second spectacular discovery. Engaged in some high temperature experiments on Carborundum, he accidentally produced graphite and gave Niagara Falls another industry.

The example of both Hall and Acheson, who signed up for Niagara power even before the Cataract company had developed it, brought a flood of electro-chemical and electro-metallurgical firms to Niagara Falls, New York, seeking cheap and plentiful power. Thus was established a symbiotic relationship between the power companies and the chemical industry. Without power, the industry had no future, but without industry, the companies had no customers. It had once been assumed that Buffalo would be the major customer. Now it was clear that the industry would concentrate on the spot, as close to the power source as possible, just as Evershed had contemplated.

Jacob Schoellkopf’s foresight in snapping up an apparently useless hydraulic canal was paying off. By 1896 he had completed a second generating plant, this one at the water’s edge in the Upper Great Gorge. Rivalling the newly opened plant of Niagara Power (to be named for Edward Dean Adams), it had the largest penstocks in the world and took advantage of the full drop of 210 feet to produce 34,000 horsepower. Hall’s Pittsburgh Reduction Company contracted for half its output.

By the end of the nineties, the availability of cheap power had brought eleven major companies to Niagara. By 1909 the number had risen to twenty-five. Jacob Schoellkopf did not live to see the dawn of the new century, but so great was the demand for power that his successors started work almost at once on an addition to the river plant with four times the original capacity. In 1918 Schoellkopf’s Hydraulic Power Company merged with Niagara Falls Power. Though the name Niagara Falls Power Company was retained, Jacob’s sons and grandsons controlled the new consolidated enterprise.

Most of the companies lured to Niagara by cheap power were new firms that would soon merge with others to become industrial giants with names like Union Carbide, Anaconda, American Cyanamide, Auto-Lite Battery, and Occidental Petroleum. They gave the world acetylene, alkalis, sodium, bleaches, caustic soda, chlorine – a devil’s brew of chemicals produced by electrolysis or electrothermal processes. Ironically, the very waters that produced the new power – so clean, so serene – were themselves poisoned by the residue of the chemical boom, while their surroundings were infected by contaminants that would lie dormant and undiscovered for more than half a century.

No such paradox was apparent at the time. The flamboyant Tesla had declared publicly that Buffalo, Tonawanda, and Niagara Falls would merge into the greatest city in the world – a statement that fuelled the boosterism that had seized the region. “NIAGARA LEADS THE WORLD,” the Niagara Falls

Gazette

trumpeted. In the machine age there was little place for the sublime. The hum of Tesla’s great motors took precedence over the roar of the cataract. In the minds of many, the Falls were obsolete.

One who held to this view was Lord Kelvin himself. Kelvin echoed the hopes of the electrical industry when he stated baldly in 1897, “I do not hope that our children’s children will ever see Niagara’s cataract.” As far as he was concerned, the Falls could be shut down. He believed that “the great power of the waterfall of Niagara is destined to do more good for the world than even the great benefit which the people of today possess in the scenic wonders of this renowned cataract. The originators of the work thus far carried out, and now in progress, hold a concession for the development of 450,000 horsepower from Niagara Falls. I do not believe that any such limit will bind the use of this great natural gift, and I wish that it were possible that I might live to see the future’s grand development.”

4

Utopian dreams

“Humanity’s modern servant,” as Edward Dean Adams called electricity – “the giant genie” – had changed the course of history, heralding a newer and brighter era. Nature at her most awesome had been subdued. The harnessing of her power touched off a wave of optimism about the future. Niagara’s mighty forces would benefit humanity not only materially but also morally. Electricity was clean and pure, a symbol of peace and harmony, in contrast to coal – grimy and corrupt, hidden in the murky bowels of the earth. The Columbian Exposition – the famous White City – pointed to Utopia.

The first of the Utopians was a flamboyant entrepreneur named William T. Love, who in 1893 proposed to build a “Model City” at Niagara. This carefully planned community would be big enough to hold a million people, with thousands of acres set aside for parkland that was advertised as “the most extensive and beautiful in the world.”

Hyperbole abounded. Love’s metropolis, according to his brochures, would be “the most perfect city in existence.” It was destined, indeed, “to become one of the greatest manufacturing cities in the United States,” backed as it was by unlimited power from the Falls. And like the Falls, which dwarfed everything around them, the Model City would dwarf all previous developments. “Nothing approaching it in magnitude, perfection or power, has ever before been attempted.”

Love literally beat the drum for his project, hiring brass bands and choruses to sing its praises, producing pamphlets trumpeting the advantages of cheap and sometimes free sites, and free power for new factories. He even managed to address a joint session of the New York State legislature (an uncommon privilege), which gave him, in effect,

carte blanche

to expropriate and condemn property and divert all the water he needed from the Niagara River for his power project. The centrepiece of his plan would be a seven-mile, navigable power canal, bringing water to a point above the Model City, where the drop to the river would provide 100,000 horsepower.

Love actually laid out streets and built a few houses and a factory before he ran out of money. The depression of the nineties was blamed, but one cannot escape the conclusion that Love’s reach was far beyond his grasp, and that depression or no depression his grandiose real-estate scheme would have foundered. He had managed to dig no more than a mile of his proposed canal, which lingered on, long after his death, a soggy monument to his failed ambitions. Over the years rains filled the ditch; children used it as a swimming hole in the summer and a skating rink in the winter. More than eight decades after his vision, Love’s canal was once more in the headlines, a symbol not of the purity of Niagara’s power but of its corruption. Utopia had become purgatory.

One year after William Love proposed his Model City, another idealist, a one-time bottle-cap salesman and smalltime inventor, proposed his own version of Utopia at the Falls. His name was King Camp Gillette, and what he envisaged was a mammoth city that would make Love’s look like a village. It would not be just another city; it would be the

only

city on the continent, housing almost the entire population of the United States and feeding on the Falls’ apparently limitless power. Gillette called it Metropolis, and, as he described it, it bears an uncanny resemblance to Fritz Lang’s film of the same name, produced thirty-two years later.

Gillette’s detailed plan for Metropolis, published in a 150-page paperback book entitled

The Human Drift

, might have been dismissed as the ravings of a lunatic save for one thing. The following year, 1895, he had a second intuitive flash and invented the Gillette Safety Razor. With his picture on every package of blue blades – curly black hair, drooping moustache – he soon became one of the most widely recognized human beings in the world.

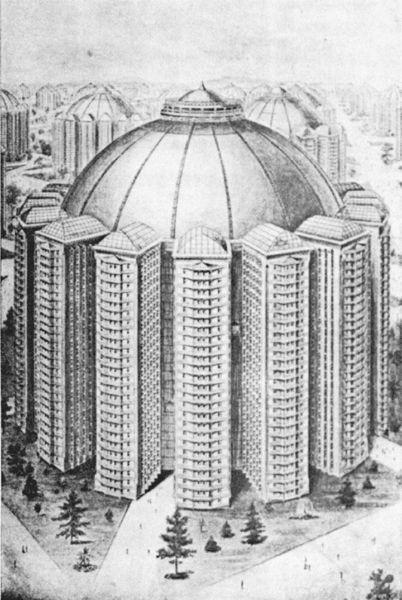

One of the huge apartment building in Gillette’s Metropolis

He was also one of the most puzzling – a product of invention’s golden age, an example of the Alger hero, and an embryonic millionaire who railed against the system that nurtured him, who taught that the doctrine of individualism was a disease, who lambasted both wealth and competition. He was out to destroy capitalism, which he thought of as a dirty, rotten and inefficient system. Would he have postulated his revolutionary theories had his invention and subsequent wealth come first? Perhaps; perhaps not. For the fact remains that Gillette held to that philosophy for the rest of his life – until his death in 1932. Indeed, he used his wealth to promote his ideals. By 1910 he was rich enough to offer Theodore Roosevelt a million dollars to act as president of his Utopia, a position that the hero of San Juan Hill quickly declined.

Gillette was in his fortieth year when he published

The Human Drift

. The son of a small businessman and part-time inventor who had lost everything in the Chicago fire of 1871, he set off on his own as a travelling salesman, eventually peddling bottle stoppers for the Crown Cork & Seal Company. It was William Painter, the inventor of the Crown cork, who gave him the piece of advice that eventually led to the invention of the safety razor: “Try to think of something like Crown Cork; when once used, it is thrown away and the customer keeps coming back for more.”

With Painter’s words percolating quietly in his subconscious, Gillette had his first flash of inspiration. Looking out of his hotel window in Scranton one wet day, he noticed a grocery truck that had broken down on its way from the wholesalers to the railroad depot. The resultant traffic snarl convinced him that there must be a more economical and efficient system of distribution. What was needed, Gillette reasoned, was a world corporation to replace the present system.

As its frontispiece,

The Human Drift

carried a photograph of Niagara Falls. But, though Gillette was obsessed by the idea of building a garden city on a scale never before conceived, the beauty of the waterfall and its value as a natural attraction escaped him. In Gillette’s concept, nature must be bent to man’s will and replaced by a vast and rational pattern of geometric parks, lawns, flower beds, and hedges. It was Niagara’s raw power that interested him – that and its size.