Niagara: A History of the Falls (36 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

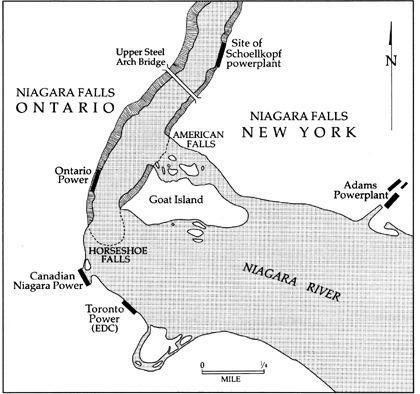

Powerplants on the Niagara River

The third member of the triumvirate, and, as it developed, the most important, was William Mackenzie. He had begun his career in Kirkfield, Ontario, as a schoolteacher. He failed in the lumber business, took a job cutting railway ties, and gravitated from that into major contracting. His fortune rested on a five-thousand-dollar loan coaxed from the Mother Superior of a Montreal convent where his wife, a Roman Catholic, had been a student. For the rest of his career, Mackenzie, a Conservative and a Calvinist, would build his growing empire on borrowed funds.

A major contractor during the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway, Mackenzie, with his strapping partner, Donald Mann, had also amalgamated and electrified the Toronto tramway system. Since 1896 Mackenzie had been busy cobbling together Canada’s third transcontinental railway, the Canadian Northern, out of a “series of disconnected and apparently unconnectable projections of steel hanging in suspense.” (Those were the words of a colleague, D.B. Hanna.) The dapper Mackenzie, with his sharp features, his neat imperial beard, and his agile mind, knew his way around the financial world. Blunt-spoken, tough-minded, and secretive, he had, in the words of the

Canadian Courier

, “a sphinx-like attitude towards the public.”

When the Montreal

Standard

produced a list of twenty-three men who formed the basis of Canadian finance, Nicholls, Pellatt, and Mackenzie were among those named. Indeed, their joint activities dovetailed neatly, to the benefit of all three. Nicholls, until 1902, was president of Mackenzie’s transcontinental railway. Mackenzie was one of ten major shareholders in Nicholls’s Canadian General Electric. Nicholls also sat on the board of Pellatt’s Toronto Electric Light Company, while Pellatt was a director of and broker for Mackenzie’s Toronto Street Railway Company. Conservatives all, fellow members of the exclusive Toronto Club, they were also among the most prominent of Toronto’s social élite.

On January 29, 1903, the syndicate was granted the right to take water from the Niagara River at Tempest Point above the Falls and to generate 125,000 electrical horsepower. The Niagara Falls Queen Victoria Park Commission was strapped for funds and set the price at a mere $30,000. The prospect was – to use a word then new in the language – electrifying.

In 1905, in an address to the Empire Club in Toronto, Nicholls rhapsodized over the “invisible and mystic power which men call electricity.” In a single poetic sentence, he delineated the magical qualities of the new energy, which was only then beginning to captivate the public. It would, he explained, “be transmitted along slender copper wires to great distances, and having silently entered our mills, factories and power houses, over still more slender wires, will, like the genie out of the bottle, expand into a force that is terrifying when uncontrolled.”

Nicholls did not dramatize, of course, the enormous profits to be made by those who controlled the genie. That year he and his partners created the Electrical Development Company as a publicly traded stock company. They then sold their $30,000 franchise to the new corporation for a staggering $6,100,000. Each took only $10,000 in cash, the rest in shares.

It was a breath-taking financial coup. They had got all their money out, made a profit, and created a six-million-dollar company with very little risk. Next they raised $5 million for construction through the sale of public bonds. But then, who could blame them for seeing an electrical future that the members of the park commission, in their myopia, had failed to grasp when they sold for $30,000 a franchise the worth of which would increase a thousandfold within twenty years?

Now these late arrivals proposed to outstrip the other two power companies operating on the Canadian side. Theirs would be the biggest and the best. The power station would be installed on a twelve-acre stretch of reclaimed riverbed, raised, in Nicholls’s colourful phrase, “from the most turbulent part of the upper rapids at Tempest Point.” That was no exaggeration. When workmen sent down sounding rods to gauge the river bottom, the flow was so fierce that it bent the metal at right angles. Nothing could be accomplished until a great wall of rocks and earth was thrown up to hold back the raging waters.

The problems the new company faced were unique, for nothing of this sort had ever before been attempted. The waters of the river, diverted down into a deep well 150 feet below the powerhouse, would rotate the big turbines at the bottom. Shafts would carry the power up to rows of generators on the ground floor of the building. The waste water would be drained away through a 2,000-foot tunnel, 150 feet below the river level. It would run to a point directly behind the Falls and discharge its effluent into the cataract itself. The tunnel would be thirty-three feet wide, the largest of its kind in the world according to the company’s boast.

Construction began at the lower end of the tunnel in 1903. A shaft 150 feet deep was sunk in the bank at the edge of the Horseshoe Falls, and a second construction tunnel driven at right angles out to the very brink, 700 feet of it under the water, to the point where the excavation for the main tunnel would commence. To save both money and time, the contractor, Anthony C. Douglass, an American from Niagara Falls, New York, decided that the debris from both tunnels would not be hauled back to shore and up the connecting shaft. Instead, it would be dumped into the chamber that the river had gnawed out between the falling sheet of water and the limestone face of the cliff over which that water tumbled.

But to accomplish this, he needed to rip a hole in the wall of the escarpment. A small opening was made near the ceiling of the construction tunnel, but thick clouds of spray from the cataract burst in. Obviously a larger opening was needed through which the tailings could be removed and the water allowed to drain out, leaving a clear passageway.

Douglass then had eighteen holes drilled into the rock face and loaded with ten cases of dynamite. The blast that resulted tore a jagged hole in the cliff, but it still wasn’t large enough. Meanwhile the tunnel, open to the spray, was filling up with water.

Douglass had a flat-bottomed boat lowered down the shaft in the river bank. The tunnel was now so full of water that the boat couldn’t clear the roof and had to be weighted down. Three miners with several boxes of dynamite and coils of copper wire then boarded the boat and started off down the tunnel, lying on their backs and propelling the craft with their hands and feet.

When they reached the opening, they placed the dynamite around it, attached the copper wire, and headed back to the shaft. Just as they reached it, their boat sank under them. They climbed to safety, and a moment later a tremendous explosion rocked the gorge. But the hole in the cliff face still wasn’t big enough.

The only solution was to apply the dynamite to the face of the cliff behind the fall of water, a dangerous enterprise. The company’s chief engineer, Hugh L. Cooper, and its resident engineer, Beverly R. Value, donned rubber suits and roped themselves together like mountain climbers. Starting from the Scenic Tunnel, long a tourist attraction, the pair headed for the opening that had previously been blasted. They scrambled precariously along the cliff face, blinded by the intensity of the spray and buffeted by the force of the wind created by the intense pressure of the falling water. Soaking wet in spite of their precautions, chilled to the bone, and thoroughly miserable, they finally reached the opening in the tunnel wall.

Here they were battered by two forces of water – the backlash churning up from the base of the Falls and the powerful jets of spray coming at them from every side. Again and again they made this journey, risking their lives each time, until they had secured four tons of dynamite around the opening, chaining the boxes into position to prevent them from being torn away by the incessant blasts of water.

This effort worked. The obstructions were at last removed, and the water ran out of the tunnel, which, as Nicholls later told an Empire Club dinner in Toronto, “is as dry and pleasant as this room.”

Meanwhile, a trickle of protests against a private Canadian company harnessing the Falls was growing to the dimensions of a tidal wave. Neither Mackenzie’s city transit company nor Pellatt’s electrical utility was popular. Both were known for gouging the public and giving inferior service. Moreover, the proponents of public power were bringing their case before the public, and it was a popular one.

The Electrical Development Company knew that it had to put up a good front, and this was undoubtedly one reason why Pellatt hired his friend E. J. Lennox, one of the country’s best-known architects, to design the powerhouse. As a result, what might have been a plain brick box became instead a neo-classical palace that in its every line seemed to suggest both power and grace. Lennox set it on the bank half a mile above the brink of the cataract, the point where the river is at its most turbulent. It was ninety-one feet wide and forty feet high, clad in pale Indiana limestone. A colonnade of massive stone pillars extended along the entire 462 feet of its front. From there visitors could goggle at the line of eleven great generators, each weighing close to two hundred tons, filling a hall so vast it was large enough to accommodate five regulation hockey rinks.

The Canadians had finally outdone all their rivals, including the Americans. But would this impressive architectural gem, perched on the very lip of the thundering river, be symbol enough to withstand the popular appeal of the public power movement?

2

The people’s power

The probability that Toronto – Hogtown, as its rivals called it – would gobble up all the Falls power did not sit well with the smaller communities of southwestern Ontario. Solid industrial towns such as Berlin and Waterloo, 70 percent of whose populations were of Germanic origin, knew that they would have to fight for their share. The only way to provide a large enough market to justify transmission of power from the Falls was to work together. No single community could go it alone.

Such was the concept that a Waterloo manufacturer, Elias Snider, brought to the local board of trade meeting in February 1902. Two days later, his friend Daniel B. Detweiler, vice-president of the neighbouring Berlin Board of Trade, preached the same gospel. The twin communities must set up a joint committee, “the sooner the better,” to look into the possibility.

From that day on, the campaign for cheap public power – “the people’s power,” as it came to be called – gathered momentum, led by Snider and Detweiler. For their communities, public power made sense. All inland towns suffered in competition with those on the lakes, which did not have to pay high freight rates to bring in coal by rail. Hydroelectric power was cheaper, but why let private industry gouge the manufacturers with exorbitant prices and poor service when a publicly owned company could provide cheaper electricity more efficiently? That was the message that the two businessmen carried to other neighbouring communities.

Popular sentiment was on their side. Suspicion of Big Business, imported from the growing antitrust movement south of the border, helped give the campaign a much-needed shove. Besides, the people of Waterloo had first-hand knowledge of the advantages of public ownership. It was one of the few municipalities that had opted for a publicly owned street railway and gas distribution system. Toronto, on the other hand, was in thrall to Mackenzie’s inadequate and inefficient privately owned transit service, which was notoriously indifferent to both public and political criticism. As Detweiler wrote to Snider, “If the new Toronto Co’y should get started they no doubt would look mainly to their own interests first and then sweat the Public all they could stand same as other Co’s.” After all, the same business cronies were involved. “The Ontario legislature must choose,” the Toronto

News

declared. “The time for decision has arrived. The people, or the Corporations?”

“The rising clamour of the multitude,” as

Saturday Night

called it, was amplified in February 1903, when seventeen municipalities, mostly from southwestern Ontario, met in Berlin to issue “the first, faint blast” in the campaign for public power. It was important enough for the mayors themselves to attend with their aldermen to hear the report of the joint committee set up the year before. It was a tentative document that merely asked for provincial legislation enabling municipalities to buy, sell, and distribute electric power.

Up rose the mayor of Toronto to toughen the resolution. He proposed that the government build and operate the transmission lines itself. The seconder, who helped push the resolution through, was the mayor of London, Adam Beck.

Almost immediately Beck took up the campaign for public power. Within a year he was its leader. His name would be linked forever with the principle of publicly owned hydroelectric power in Ontario. His larger-than-life statue would dominate Toronto’s University Avenue, opposite the Ontario Hydro building. The great generating stations flanking the Niagara gorge would all bear his name. Hated, feared, despised, and admired – even venerated – in his lifetime, he would eventually attain the status of provincial idol.