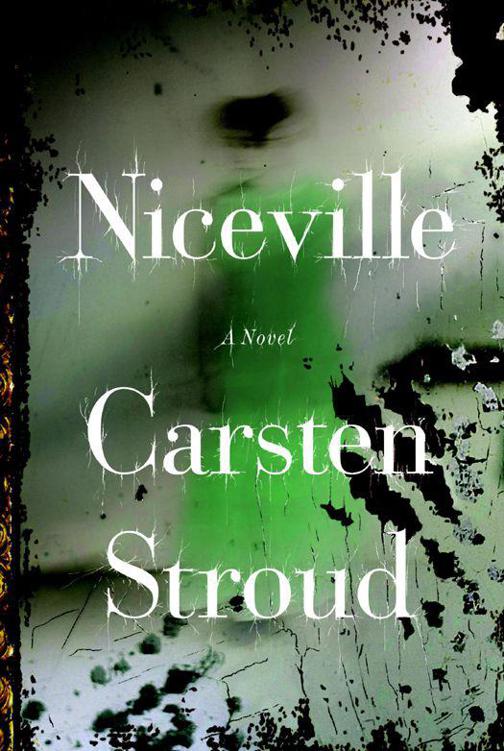

Niceville

Authors: Carsten Stroud

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright © 2012 by Espirit D’Escalier

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by

Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks

of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stroud, Carsten, 1946–

Niceville / by Carsten Stroud.—1st ed.

p. cm.

“A Borzoi book”—T.p. verso

eISBN: 978-0-307-95858-7

1. Married people—Fiction. 2. Missing children—Fiction. I. Title.

PR9199.3.S833N53 2012

813′.54—dc23 2011047306

Map by Robert Bull

Jacket images: (mirror) Lee-Ann Licini; (woman) Bodil Frendburg /

Millennium Images, UK; (frame) © Polina Kobycheva / Alamy

Jacket design by Jason Booher

v3.1

For Linda Mair

Come from the Four Winds, O Breath,

And breathe upon these slain,

that they may live.

—Monument to the Confederate Dead,

Forsyth Park

Savannah, Georgia

Malicious men may die, but malice … never.

—Molière,

Tartuffe

In less than an hour the Niceville Police Department managed to ID the last person to see the missing kid. He was a shopkeeper named Alf Pennington, who ran a used-book store on North Gwinnett, near the intersection with Kingsbane Walk. This was right along the usual route the boy, whose name was Rainey Teague, took to get from Regiopolis Prep to his house in Garrison Hills.

It was a distance of about a mile, and the ten-year-old, a rambler who liked to take his time and look in all the shop windows, usually covered it in about thirty-five minutes.

Rainey’s mother, Sylvia, a high-strung but levelheaded mom who was struggling with ovarian cancer, had the kid’s after-school snack, ham-and-cheese and pickles, all laid out in the kitchen at the family home in Garrison Hills. She was sitting at her computer, poking around on Ancestry.com with half her attention on the front door, waiting as always for Rainey to come bouncing in, glancing now and then at the time marker on the task bar.

It was 3:24, and she was picturing her boy, the child of her later years, adopted from a foster home in Sallytown after she had endured years of fruitless in vitro treatments.

A pale blond kid with large brown eyes and a gangly way of going, given to sudden silences and strange moods—she’s seeing him in her mind as if from a helicopter hovering just above the town, Niceville spread out beneath her, from the hazy brown hills of the Belfair Range in the north to the green thread of the Tulip River as it skirts the base

of Tallulah’s Wall and, widening into a ribbon, bends and turns through the heart of town. Far away to the southeast she can just make out the low coastal plains of marsh grass, and beyond that, the shimmering sea.

In this vision she sees him trudge along, his blue blazer over his shoulder, his stiff white collar unbuttoned, his gold and blue school tie tugged loose, his Harry Potter backpack dragging on his shoulders, his shoelaces undone. Now he’s coming to the rail crossing at Peachtree and Cemetery Hill—of course he looks both ways—and now he’s coming down the steep tree-lined avenue beside the rocky cliff that defines the Confederate graveyard.

Rainey.

Minutes from home.

She tapped away at the keyboard with delicate fingers, like someone playing a piano, her long black hair in her eyes, her ankles primly crossed, erect and concentrated, fighting the effects of the OxyContin she took for the pain.

She was on Ancestry because she was trying to solve a family question that had been troubling her for quite a while. At this stage of her research she felt that the answer lay in a family reunion that had taken place in 1910, at Johnny Mullryne’s plantation near Savannah. Sylvia was distantly related to the Mullrynes, who had founded the plantation long before the War of Secession.

Later she told the uniform cop who caught the call that she got lost in that Ancestry search for a bit, time-drifting, she said, one of the effects of OxyContin, and when she looked at the clock again, this time with a tiny ripple of concern, it was 3:55. Rainey was ten minutes late.

She pushed her chair back from her computer desk and went down the long main hall towards the stained-glass door with the hand-carved mahogany arches and stepped out on the wide stone porch, a tall, slender woman in a crisp black dress, silver at her throat, wearing red patent leather ballet flats. She folded her arms across her chest and craned to the left to see if he was coming along the oak-shaded avenue.

Garrison Hills was one of the prettiest neighborhoods in Niceville and the sepia light of old money lay upon it, filtering through the live oaks and the gray wisps of Spanish moss, shining down on the lawns and shimmering on the roofs of the old mansions up and down the street.

There was no little boy shuffling along the walk. There was no one around at all. No matter how hard she stared, the street stayed empty.

She stood there for a while longer, her mild concern changing into exasperation and, after another three minutes, into a more active concern, though not yet shifting into panic.

She went back inside the house and picked up the phone that was on the antique sideboard by the entrance, hit button 3 and speed-dialed Rainey’s cell phone number, listened to it ring, each ring ticking up her concern another degree. She counted fifteen and didn’t wait for the sixteenth.

She pressed the disconnect button, then used the number 4 speed-dial key to ring up the registrar’s office at Regiopolis Prep and got Father Casey on the third ring, who confirmed that Rainey had left the school at two minutes after three, part of the usual lemming stampede of chattering boys in their gray slacks and white shirts and blue blazers with the gold-thread crest of Regiopolis on the pockets.

Father Casey picked up on her tone right away and said he’d head out on foot to retrace Rainey’s path along North Gwinnett all the way down to Long Reach Boulevard.

They confirmed each other’s cell numbers and she picked up her car keys and went down the steps and into the double-car garage—her husband, Miles, an investment banker, was still at his office down in Cap City—where she started up her red Porsche Cayenne—red was her favorite color—and backed it down the cobbled drive, her head full of white noise and her chest wrapped in barbed wire.

Halfway along North Gwinnett she spotted Father Casey on foot in the dense crowd of strolling shoppers, a black-suited figure in a clerical collar, over six feet, built like a linebacker, his red face flushed with concern.

She pulled over and rolled down her window and they conferred for about a minute, people slowing to watch them talk, a good-looking young Jesuit in a bit of a lather talking in low and intense tones to a very pretty middle-aged woman in a bright red Cayenne.

At the end of that taut and urgent exchange Father Casey pushed away from the Cayenne and went to check out every alley and park between the school and Garrison Hills, and Sylvia Teague picked up her cell phone, took a deep breath, said a quick prayer to Saint Christopher,

and called in the cops, who said they’d send a sergeant immediately and would she please stay right where she was.

So she did, and there she sat, in the leather-scented interior of the Cayenne, and she stared out at the traffic on North Gwinnett, waiting, trying not to think about anything at all, while the town of Niceville swirled around her, a sleepy Southern town where she had lived all of her life.

Regiopolis Prep and this part of North Gwinnett were deep in the dappled shadows of downtown Niceville, an old-fashioned place almost completely shaded by massive live oaks, their heavy branches knit together by dense traceries of power lines. The shops and most of the houses in the town were redbrick and brass in the Craftsman style, set back on shady avenues and wide cobbled streets lined with cast-iron streetlamps. Navy-blue-and-gold-colored streetcars as heavy as tanks rumbled past the Cayenne, their vibration shivering up through the steering wheel in her hands.