Nightingale

Authors: Aleksandr Voinov

Nightingale

Aleksandr Voinov

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the authors’ imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Nightingale

Copyright © 2015 by Aleksandr Voinov

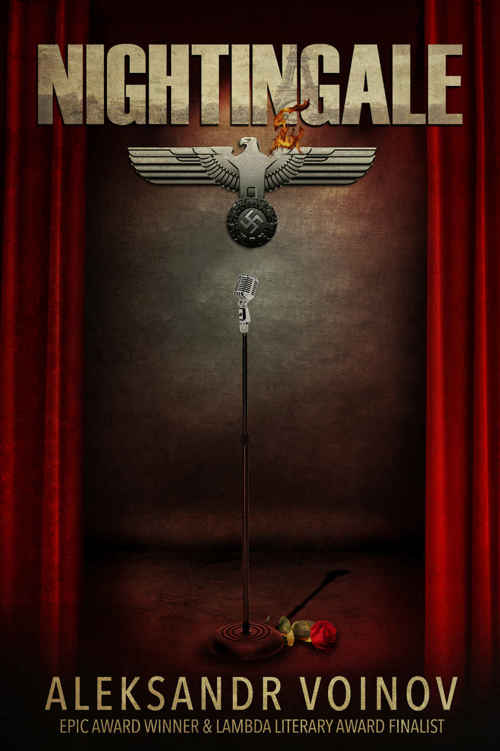

Cover Art: L.A. Witt/L.C. Chase

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher, and where permitted by law. Reviewers may quote brief passages in a review. To request permission and all other inquiries, contact the author at

[email protected]

.

First edition

November, 2015

About Nightingale

In Nazi-occupied Paris, most Frenchmen tread warily, but gay nightclub singer Yves Lacroix puts himself in the spotlight with every performance. As a veteran of France’s doomed defense, a survivor of a prison camp, and a “degenerate,” he knows he’s a target. His comic stage persona disguises a shamed, angry heart and gut-wrenching fear for a sister embedded in the Resistance.

Yet Yves ascends the hierarchy of Parisian nightlife to become a star, attracting the attention—and the protection—of the Nazi Oberst Heinrich von Starck. To complicate matters further, young foot soldier Falk Harfner’s naïve adoration of Yves threatens everything he’s worked for. So does Aryan ideologue von Grimmstein, rival to von Starck, who sees something “a bit like a Jew” in Yves.

When an ill-chosen quip can mean torture at the hands of the Gestapo, being the acclaimed Nightingale of Paris might cost Yves his music

and

his life.

“Celebrated jesters are the most melancholy of men.”

—Maurice Chevalier

Chapter 1

Reluctant to make his way through the German crowd in the front of the cabaret, Yves ducked out the back. After slipping the cigarette between his lips, he paused to pat his coat for a lighter. Had he put it back into the inner pocket by accident—the one that had been torn for months now? If so, it was gone, or, if he was lucky, somewhere in the gloom of the bar.

A movement at the opening of the alley. Several people, a surprised word of protest—Yves stepped back, sliding a hand into his trouser pocket, where it came across the metal square of the lighter. The scuffle not twenty meters away turned frantic; arms and legs flailed. Somebody being robbed?

Pained huffs, as one robber punched the dark silhouette of a man in the stomach while the others held him in place against the wall.

Then suddenly a shout from afar, and the attackers turned tail and ran.

Breathlessly, Yves watched the figure crumple to the ground.

No movement, nobody else in the alley. His skin crawled with dread. He should not get involved. Maybe somebody else would find the man, or he’d get up and walk away once he’d recovered. But how the body lay there gave Yves a shiver. Something was very wrong.

He pushed away from the wall and walked toward the fallen man, toward the light of one sickly street lamp, and the sounds and bustle of Montmartre before curfew. The light spilling into the alley, transformed the man’s clothes into a uniform. Yves’s leg twitched as if his shin had brushed something invisible.

He should walk on, get out of the alley and run. Or turn and go back into the bar.

But how could he abandon those glassy, pale eyes looking up at him? The man could have been a corpse with that stare, not unlike the Frenchmen who had died defending Paris, left to fester in the June sun. But dead men didn’t blink, didn’t gasp for breath.

Yves crouched and touched the man’s cold sweaty face, noticed that he tried to move away a little, as if Yves meant him harm. And—did he? Yves glanced down to the soldier’s hand clutching against his stomach. Only then did he catch the heavy smell of blood. The soldier had been knifed, just like that, while his comrades were getting drunk and raucous a few yards away inside Chez Martine.

To his shame, Yves immediately thought

They will kill us all for this.

The thought was followed by a retching wave of fear rather than pity or compassion. He should probably leave the man to die, then hide the body and flee the city before the Germans caught wind of this. Maybe Madeleine would help him hide. As long as there were no witnesses—

Steps passed by on the pavement, and Yves jumped, half expecting a policeman to ask what he was doing. If they suspected him, there was no telling what would happen.

The man’s lips opened, moved tonelessly. Pain flitted over his features, but most of what Yves saw in that face was astonishment. He let go of the lighter, and once he’d pulled his hand out of his pocket, he couldn’t stop himself.

“This might hurt,” he said before he remembered that most Germans didn’t speak French. Maybe it still sounded reassuring. He pulled the man up by his shoulders, helped by mostly coordinated movements from the man’s legs that braced him up against the wall, despite the grimace of pain and the groans pressed out between gritted teeth. The light reflected off the wetness at the front of the uniform and tore the bright red stain on the man’s hands out of the shadow. If the soldier now staggered back to his unit, everybody inside Chez Martine would pay the price. He couldn’t allow that.

“We have to get you to a hospital,” he urged, then repeated “Hospital,” hoping that the German word would at least be similar.

The soldier gritted his teeth and nodded. With surprising strength, he slung his arm around Yves’s shoulders, his bloodied fingers a tight fist not far from Yves’s face, the other hand clutching at his stomach.

“

Kommunisten

,” the man growled low.

Which was a fair guess. It might have been the Communists. Who else would rise up and fight the Fascists? They were off the chain ever since Hitler had invaded the Soviet Union. Améry had been talking about how “Moscow” had previously forbidden attacking the Germans. Now that the Nazi tanks were rolling toward Moscow, all bets were off.

Or maybe it had been

pétainistes

enraged at a snub—imagined or real. Or just robbers, but why would a criminal attack an SS soldier when there was much easier prey to be had? No, this had been deliberate.

And, Yves reminded himself, they might still be out there, watching. He put an arm around the man’s waist and had to re-grip when he accidentally touched the leather holster and flinched as if he’d grasped a viper.

Slowly, he maneuvered the soldier out of the alley, onto the pavement, and away from the Chez Martine. Supporting the soldier was hard—hailing a

vélo

-taxi with a heavy man draped on him was even harder. At least he could hope that most people would only think him drunk.

One cyclist slowed on the street, craned his neck, then accelerated just as Yves’s hopes began to rise. If only the Germans hadn’t rationed fuel, there would have been car taxis on the street, but anybody driving a car now was either collaborating with the Germans, or, well, German. Either way, that wouldn’t turn out so well. When the cyclist rushed past him, Yves bit down on a curse. No reason to make a scene—and attract attention.

When the next

vélo

-taxi approached, the German raised his arm in a harsh, commanding gesture. Yves assumed the driver thought the bloodstains were gloves, because, indeed, the taxi stopped. Yves helped the German get to the passenger’s seat. The soldier almost fell into it, leaning his head heavily against the back.

The cyclist pulled a cigarette from his breast pocket and lit it, inhaling the smoke so deeply it made Yves’s lungs itch with craving. “Where to?”

Yves glanced at the soldier, at the wet uniform, the way he looked pale and sweaty, the skin as unnatural as wax. Despite better knowledge, he got into the seat alongside him, after he’d picked up one lifeless hand by the cuff of the uniform and placed it in the soldier’s lap, hoping the gesture looked a lot less bizarre than it felt. “Hôpital Claude Bernard.”

The taxi driver half turned toward them. “Is he alright?”

“He’ll be fine.”

If he gets a surgeon and a blood transfusion

. He shrugged. “Might have eaten something bad. Can’t have him die in our place.”

The taxi driver nodded and stepped into the pedal. Yves craved nothing more than that evasive cigarette, but when his gaze fell again on the German’s stomach, he craved it mostly to drown out the smell of the blood that seemed as intense as taste now, coating the back of his throat.

It brought back thoughts he didn’t like having, didn’t like remembering. Of the chaos of the invasion, the way the Germans had dispatched what was left of the French army, and how the Germans had themselves seemed stunned by their fast victory and unprepared to deal with so many prisoners. His own capture and imprisonment, blurred by the shock and daze and pitiful gratitude to be alive when others weren’t. He just didn’t have the stomach to kill. To his knowledge, he hadn’t killed, but he couldn’t have said for sure. It had all been too confusing, very much unlike the heroic tales he’d believed as a child. Only after his own return had he really understood the expression in the eyes of the previous generation, the

mutilés de guerre

with their missing joy and missing limbs. Yet, they had been victors, very much unlike himself. They had been celebrated, regardless of how little was left of many of them—unlike this sad, embarrassed army.

He’d spent most of his time in uniform writing songs and debating politics with other urban Parisians, had even made a stab at short stories when one of the writers told him he had talent.

During imprisonment, though, he’d been unable to write. But he’d remembered the songs like they were written on his own flesh. He’d sung them to any who’d hear them. Those performances had bolstered what was left of their spirit. Many felt they’d been more important to survival than bread.

The German next to him grunted. Yves glanced up to his face, noticing the glassy stare fixed on him, and wasn’t sure if that sound was from pain or an attempt to speak.

He was about to ask, but then the driver slowed, and he recognized the gate of the hospital. He dug into his pocket for money and clearly overpaid, just in case the German’s blood had spilled on the seats. But what if the driver remembered him because of that? Then again, how many incapacitated German soldiers would use that

vélo

-taxi tonight?

Yves helped the German stagger toward the hospital and was relieved when the medical staff took the man off his hands.

Within moments, the German was being wheeled away, a slumped dark figure amidst the starched white of the nurses. Yves breathed a sigh of relief, not sure if he should hope that the man would live or die—less because of compassion than the inevitable reprisals. The Nazis killed hostages for every loss they suffered in Paris, shooting twenty, fifty, or more for every one of theirs. In truth, all of Paris was their hostage, and good behavior both expected and common sense.

Chapter 2

Onstage, Yves rehearsed his new bracket with Martine’s piano player before a mostly empty room. Without a raucous crowd filling up Chez Martine and drowning out most of what he was singing, the old anxiety had more room to spread its thousand ugly wings that beat against his rib cage, robbing him of his breath. No audience to woo and flatter, no mood to read and play against.

He sang

Mills on the River

, friendly, optimistic, and slow, about the sunlight outside the city and the reflection of the mills in the water. Two things were safe to sing about—France and love, and France only if it wasn’t too patriotic. Albeit where exactly the German masters drew the line was up for debate. He’d heard some

chanteurs

stretch those tenuous limits. And love . . . ah, love. He could only speak in riddles, quickly inserting a few wrong letters in the right places.

Despite the venomous doubts that hissed through his mind before he started singing, once he did sing, his voice always came easy. The notes obediently lined up where they should go, sounding clear and strong here where he did not have to sing against chatter, drunken laughter, and smoke. Over at the bar, several of the dancing girls sat while Benoît, Martine’s older son, polished glasses.

The back door burst open, and thirteen-year-old Nicolas came running in. “Look what I got!” he shouted.

Yves’s voice faltered. The cap. He cleared his throat, but suddenly the melody was gone, overwhelmed by a feeling like fingernails against the back of his neck. Two of the dancers looked over to him, so he feigned that he was done and walked offstage to pour himself a glass of water. “Where did you find that?”

“Just in the alley! Can I keep it?” The boy beamed up at him, putting the hat on his head. Black cloth, silver skull, the Eagle of the Reich spreading its wings from the tip.

“That is not a toy, Nic.” Yves pulled a cigarette from his pocket.

The boy pursed his lips. “But he left it behind.”

“Who?”

“The soldier. Must have been a soldier, right?”

Martine appeared from behind the stage, and faster than anyone would have expected, came up behind her son, snatched the cap, and smacked him over the mouth. “Don’t touch that! That’s from

them

!”

Nic’s more-shocked-than-surprised wail stopped the dancers’ chatter for a moment. Then the boy turned on his heel and rushed off, the wooden soles of his shoes clattering.

Martine tossed the cap onto the table with disgust, looking as if she’d found a dead rat in her beer cellar. “Typical,” she sneered as if leaving the cap behind were a personal insult to her and her establishment. “As if we didn’t see enough of them.”

Yves looked at the cap, abandoned, possibly the last thing of the dying or dead man he’d ever see, yet real and menacing like a nightmare just before waking.

“I’ll take care of it.” He didn’t want to risk drawing the displeasure of the Germans—he wasn’t going to walk into the

mairie

or hand it over at one of the cafés or cinemas that the Germans had reserved for themselves. And going to one of their barracks or even the Kommandantur was impossible. He didn’t want to draw their attention, least of all the SS’s or the Gestapo’s. They’d ask what had happened to the soldier it belonged to, and since he had no satisfying answer beyond “in hospital,” he’d better stay clear of this. In this day and age, he’d likely be interrogated, and he didn’t expect the Germans to believe him when he said he hadn’t seen the attackers clearly enough.

Martine left and returned with a sheet of brown paper to wrap the hat in and closed it with a piece of string. It could be anything now, but Yves knew there was a silver skull sleeping inside the paper.

He deposited the hat in his dressing room and pushed it from his mind.

An hour later, he opened the evening at Chez Martine, not the most prestigious spot. On the one hand, he hated starting with a cold audience, but on the other hand, they were mostly sober this early, and his comedy routine at least always bridged the gap.

And he did have other plans for later. Normally, he covered three bars, cafés, or cabarets before curfew, but this would be his only show tonight.

As always when he took the stage, a number of Germans was firmly ensconced in the front of the cabaret, a wall of gray and green uniforms and polished boots, medals on display. How used he’d gotten to the view of about three rows of

boches

laying siege to his stage. Most wouldn’t speak enough French to laugh at his jokes, and even those that spoke French would struggle with the Parisian argot of his rowdier numbers. A small protection, come to think of it, but it filled his heart with an odd sense of pride that Paris didn’t share everything with strangers that she shared with her children.

He inhaled and let his stage persona come over him—simple, good-hearted, with the wisdom of fools, delivering his welcome, singling out ladies in the audience for compliments and their male escorts for some good-hearted banter that looked so easy, only delivering the punch line in an afterthought.

Within fifteen minutes, the audience was warmed up, with some guests roaring laughter. He broke into the first song, picking up on the mood in the audience with a cheeky song about Parisian traffic. Since they were all reduced to riding bicycles, he painted a picture of lovers, artists, even bankers riding their

vélos

through the city. The refrain was silly—“I’m riding my

vélo

,

vélo

,

vélo

”—but the audience loved it.

Even the Germans broke into song; the tune was catchy enough to stir the heavy, Teutonic hearts in those gray uniforms, giving him a strange pleasure. It was easy enough to imagine they were just “audience,” part of it all, and even though they trampled all over France, they at least appreciated her culture.

He sung the other catchy, fast ones, then segued into some more comedy to catch his breath. The audience followed him as he did the funny, somewhat touching series of anecdotes about his neighbor’s dog (an animal clearly smarter than her owner), then sung a few of the slower, more romantic songs, then

Mills on the River

, his current favorite and the finishing song. The rapt silence after that one warmed his heart. Even the Germans looked wistful. Then whoops and cheers and applause.

They called him back twice, and every time he combined a few jokes with a short song, leaving the audience with that perfect glow of release, faces and hearts open to him. He smiled and waved

au revoir

before he finally managed to get off the stage, squeezing past the dancing girls who’d ensure that at least the men in the audience wouldn’t miss him.

Back in the dressing room, he mopped his brow with a towel. Considering what a pain it was to get makeup off and the fact that he usually did several engagements per night, he’d quickly given up on the greasepaint and went without. He changed out of his stage clothes, which he kept at Martine’s, and into a more formal suit, then lit a cigarette, inhaling the smoke greedily, gradually calming from the post-performance buzz.

Martine came by to hand him the money in an envelope just as he slipped into his coat. “Where are you going now?”

“I’m just meeting friends for dinner. I’ll deal with the . . . thing Nic found.” He picked up the hat in its wrapper and smiled at Martine. “I’ll be back tomorrow evening.”

“Be careful. You do have a beautiful voice, you know,” she said somewhat gruffly, as if she was accusing him of putting it at risk.

“And that’s why nobody is going to harm me.” He brushed all thoughts of the

boche

aside, kissed her cheeks, and strode out into the balmy Parisian evening.

He took the Métro, watching the other passengers, none of whom seemed to recognize him, which was just as well. His stage persona was quite different, and he often felt like he’d spent it all by the time the final note had left him. Offstage, he was empty of wit and jokes and much less charming than the man the audience saw. His sister Édith called him “smaller than life,” which from her wasn’t meant as an insult—he thought, at least.

The concierge let him in, giving him only a brief nod. Yves studied the wrought iron of the elevator cage on the way up, noticing, again, that the metal was shaped like roses. It seemed like a fitting metaphor for love, this elevator cage, but he didn’t think anybody would get the reference if he used it for a song. So he wouldn’t. This was something for a prose writer.

Madame

Julia’s apartment took most of the upper floor of the house, and they let him in after one knock. Her butler took his coat and ushered him inside. “Most of the other guests have already arrived,

monsieur

,” the butler said with an English accent. Yves wondered for a moment how the man had escaped being rounded up as an enemy alien and thrown into one of the camps. But then, Julia’s influence and power—and above all, her connections—protected the lesser beings in her entourage.

He thanked the butler with a nod and stepped into the Chinese salon, with its fine silken carpets in cream and transparent light blue and expensive porcelain on display.

Julia’s head turned and she gave him one of her wide, beautiful smiles as she extricated herself from the gentlemen next to her. She swooped in, plucking a champagne flute on the way. “Oh, Yves, how delightful that you could make it.”

He couldn’t help but smile, glancing quickly over at the other guests. “I don’t know what you want with a frivolous little singer like me if you have the men of

les belles-lettres

and half the

Académie française

gathered.”

She laughed at him. “At least you will not steal away the conversation and put it into your next novel.”

“No, the worst that could happen is that you’d end up in one of my songs.”

“And what kind of song would that be?”

“A love song, of course. The ravishing American who stole my heart.”

“You charmer.” She winked. “I’m glad you’ve come back. I was worried that we’d repelled you.”

“Fifty horses couldn’t have kept me away—but I did agree to talk to Maurice.”

“Oh, you’ll sing at the Palace? You’re forgiven, darling.” Before he could correct her, she took his arm and led him to her companions: serious-looking, acclaimed novelists that immediately made him feel inadequate.

As much as he admired the grave men of letters, his world was all sound. Even in his few, hidden short stories, he aimed to capture a tone and melody, often going nowhere specific. When he wrote, it was like whistling when walking in the street, a way to pass the time and capture an errant thought. These men comported themselves as the guardians of France’s culture, her mind and thoughts. And while Yves knew his art would most likely be forgotten in the next season, these men aimed for nothing less than eternity.

They seemed to look upon him with a sense of indulgence. One of them drew his eyebrows together when he explained that while he was a singer, he did not actually sing at the

Opéra

.

“Oh, but I thought I’d heard your name before.”

“My mother,

monsieur

.”

At which point the frown deepened, spreading across his whole forehead. How somebody with a lyric

mezzo-soprano

for a mother could turn out to be a popular crooner on the chanson circuit was possibly beyond the real

artiste

.

Yves still smiled and eventually made good his escape, joining instead a smallish detachment of Modernist painters who stood near one of the large Chinese vases, debating agitatedly about paintings Yves hadn’t seen. Yves enjoyed watching them, red-faced and passionate, when somebody touched him lightly on the shoulder. He turned, coming face-to-face with Julia and . . . a German officer.

“Yves, may I introduce you to Oberst Heinrich von Starck.”

The oberst promptly clicked his heels together, which made Yves wince, and he hoped the oberst hadn’t caught that. But, thank God, the man did not give him a Hitler salute. “My pleasure,

Monsieur

Lacroix.” Instead, he smartly extended a hand, and Yves had to take it or risk a scene.

“Oberst.” He was at a loss for words, suddenly captured by deep blue eyes that reminded him of Cab Calloway’s song

Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea

. The notion almost made him laugh, even more so because he had to fight the urge to break out into a version of the song. He should adapt it for his own repertoire. He could do worse than bring a dash of Cotton Club to Paris.

The oberst seemed a little surprised, but smiled back at him. “Such a smile is unique, even in Paris.” His French was slightly accented, but nevertheless elegant.

Yves cleared his throat. “I wouldn’t have taken you for a connoisseur of smiles,” he said low, noticing Julia’s amusement from the corner of his eye. He was safe with her; part of her pleasure was to surround herself with men who groomed and preened for the benefit of other men. Not that she was above taking the occasional artist into her bed, and her old husband, in turn, enjoyed life to the fullest in Cannes. It was an arrangement that suited them both.