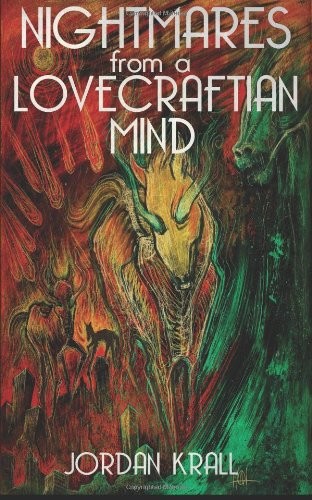

Nightmares From a Lovecraftian Mind

Read Nightmares From a Lovecraftian Mind Online

Authors: Jordan Krall

Tags: #Horror, #Short Stories (Single Author), #Kindle

Jordan

Krall

Nightmares of a

Pampiniform

Mind

© 2011 Jordan

Krall

and originally appeared in the AKLONOMICON anthology.

His Candescence,

A

Reptant

Hell and Hail Desire

and

The Bodies of Cold Gentlemen ©

2011 Jordan

Krall

and were previously published in UNFRUITFUL WORKS but have been slightly

revised for this collection.

And You Should

Believe in Solar Lodges

© 2011 Jordan

Krall

and

was previously published in the COPELAND VALLEY SAMPLER.

Argon Seizure

©

2012 Jordan

Krall

and was originally included in

FALSE

MAGIC

KINGDOM

.

All

other material © 2012 Jordan

Krall

and our original

to this collection.

Cover art by Mike

Lamb.

Matthew Revert

Published by

Respectfully

Dedicated

to

Wilum

H.

Pugmire

CONTENTS

WE SHOUT OUR OMENS

WHY OUR FATHER LEFT US

A REPTANT HELL

XNOYBISTIC FRAGMENTS FOUND IN AN INDUSTRIAL PARK

HAIL DESIRE AND THE BODIES OF COLD GENTLEMEN

NIGHTMARES OF A PAMPINIFORM MIND

OUR UNRELIABLE STRUCTURES

AND YOU SHOULD BELIEVE IN SOLAR LODGES

I discovered the works of H.P.

Lovecraft

at the impressionable age of 12. That was about

around the same time my parents were taking me on countless vacations to

Atlantic City

,

New Jersey

. I even bought a copy of

Lurker at the Threshold

in a bookstore

on the boardwalk. It was at this time that I started to write a small amount of

horror fiction. Because of this I associate HPL with that city. Those towering

hotels strike me as very sinister as does the ocean across the boardwalk. I

also refuse to step foot in the ocean (though this is probably only partially

due to

Lovecraft’s

watery horrors. Since I was a

small child, I often worried about my father going too far into the ocean and

the possibility of his being lost terrified me). This information is just

background of my fearful nostalgia.

So from age 12 I was influenced by the hints

of cosmic horrors and the earthly cults that worshipped them. I think that was

the part that scared me the most: that there was the possibility that seemingly

normal people could harbor such infernal interests. These cult members could be

of an intellectual sort, both fanatical and educated. To me, that was and is a

frightening combination.

I did not begin to write fiction seriously

until I was in my mid 20s and by that time I knew I was not going to be able to

emulate the prose style of

Lovecraft

despite my

adoration of his work. But I never really thought I had to. I needed to have my

own style, my own voice, and try to pass on that feeling of dread and cosmic

otherness to the reader on my own terms. That’s what you are going to be

reading in this book: stories and prose poems that encompass my own fears of

personal, physical, and cosmic horrors.

I am fully aware there are

Lovecraftian

purists who snub their noses at anything that

deviates from their definition of what constitutes good

Lovecraftian

writing or anything that has the wee bit of sex or violence. This is the 21

st

century and for a genre (or sub-genre) to stay fresh, we need to let modern

sensibilities seep through. But that is only my opinion.

As a warning, there is one story in this

collection that may offend some whose tastes are old-fashioned. That story is

Nightmares

of a

Pampiniform

Mind

which was written for the

AKLONOMICON anthology published by

Aklo

Press. Those

with weak stomachs may feel free to skip that one. However, if you are indeed

willing to read it, I ask that you do so with an open mind. You will not find

anything extremely gratuitous. Instead, you will find a writer trying to write

through the cosmic terror in his own voice, in his own way.

Also, you will

not

find a copious

number of

Cthulhu

Mythos references. There may be a

handful of references in one story (

Nightmares

of a

Pampiniform

Mind

) but as a whole, I have not

followed suit with most mythos writers. Instead, I tried to channel the

nightmares

Lovecraft

(and other

Lovecraftian

writers) has given me into something personal.

Well, here we go….into the ocean I am

terrified of, into the cosmic nightmares I truly know exist.

Jordan

Krall

,

East Brunswick

,

2012

SHOUT OUR OMENS

Our shouting does

not open the gates for there are no gates. Our pleading does not pave the way

for there is no way. Our hearts do not beat for the universe for there is no

universe and we have no hearts.

As our voices lay

like concrete upon the weakening foundation of our father’s homestead, we

realize the prices we will have to pay are astronomical. Still, the omens we

speak, the ones we shout and declare, are simple ripples in the pond of our

insignificance.

But we still have

the omens.

They are our own.

They are ours to keep locked within our wooden skulls, the skulls some have

opened to reveal our brains and count the rings. Our brains, those simple grey

kites confused in the wind, playing pretend in morbid minstrel shows:

pockmarked dolls spitting and swearing for the amusement of those tourists

brave, or bored, enough to stop and stare at us.

Our brains tell us

our omens are true, but blanketed in false starts and illusionary symbols. We

cannot stutter forever…despite our tongues that are stiffened and paralyzed by

fear of the inevitable.

Our omens

must

be true.

Our own grey

matter

magick

would not deceive us.

Our speech is lost

in the heavy breath of those oblivious deities we’ve ignored, those deities who

have despised us and our infantile projections, expectations, and rebirth. But

our omens must be true for they have brought us here.

They have brought

us back to the womb.

Our omens must be

true.

It began with a

visit to the doctor and ended with a trip to the moon.

Of course, our

father was scheduled to go to the moon well before his visit to the doctor. But

that appointment is what led him to believe that I,

his only son

, was

the cause of his long dormant insanity that had begun to manifest itself in his

erratic behavior. You may not have noticed this behavior because your

relationship with him has been strained over the years but if you had been

here, you would have seen it: his reading books in languages he did not

understand, ignoring life long friends he encountered on the street, dressing in

clothing that looked more eighteenth century than twenty-first. These are the

things he did in your absence.

And he blamed all

of it on me.

It was gradual,

this blaming, and if I had known what was to happen, I wouldn’t have even

driven father to his doctor’s appointment. If I had known this so-called

professional physician was going to reinforce or encourage the paranoid mental

processes of our father, I would have chosen another one. Why should I take the

blame for the disease of another person? It is clear his condition was a latent

one, gathering momentum throughout his life, before my birth and through his

marriage to our mother. Why should it be the son who is responsible for the

father’s mental and physical failures?

But I am not one

to complain. I can only make observations.

Before his

departure to the moon, father mailed me a large black envelope which contained

six hundred and five type-written pages. I have no doubt he typed them up all

himself on that archaic little typewriter mother had gotten him for an

anniversary gift so many years ago.

The paper he had

used was thin, almost translucent and apparently he did not believe in

traditional margins as the words came a quarter of an inch to the edges of the

paper as if he needed to squeeze in as much as on the skin-like paper as

possible.

You probably want

to know what our father had typed but I cannot sum the content up without

dizzying myself into some manic state of untranslatable insanity. He had typed

up English words, yes, but in such a blasphemous combination, a hypnotic code

of syllables and punctuation that was exhausting to read. I could not finish it

because I imagined father laughing to himself as he thought of my perusing his

six hundred and five page declaration of blame and I was unwilling to give him

the satisfaction.

I threw the

manuscript in the trash. If he was to ask me where the pages were, I was

planning to tell him I sent it to the moon, that it was waiting for him there.

I am sure he would not have appreciated my sense of humor.

But he never did

ask about it.

The day before he

was to launch, though, he telephoned me.

“I’m leaving

tomorrow, son.”

“I know.”

“You have anything

to say?”

“You called

me

. Do

you

have anything to say?”

No response.

Then I said, “I hope

you have a safe flight.” But I really didn’t mean it. I hadn’t cared either

way.

“No flight is ever

safe,” he said.

“Well then…”

“But you could

apologize.”

“Apologize for

what

?”

A

heavy sigh from father.

“For

what

?”

I repeated my question

even though I knew what I needed to apologize for.

“There’s iron at

the core of the moon, more than was previously thought, I mean.

Oceans, too, magma, something like pyramidal faces.

I’m

going to be seeing it all. I’m going to

study

them.”

“Do I need to know

this? Will this help me?”

“Nothing will help

you, son.”

“So why tell me?”

“Because

I have nothing else to say to you.

Nothing at all,

son.”

Then he hung up

the phone.

I did not watch

the launch on television the next day but I dreamt about it. I dreamt my father

went up there alone. He was dressed not for space but for some semi-formal

affair. His hair was slicked back and his mustache neatly trimmed. He had used

some extremely pungent mouthwash that made my dream-eyes water. When he reached

the moon, he explored a crater and found the black envelope containing the

manuscript he had sent to me. He chuckled and read it aloud in my dream and I

was forced to listen to every word.

The following day

I made an appointment with my father’s doctor. I see him this evening,

actually. I hope I can get to the bottom of this. I will insist the doctor

explain himself, to explain my father’s condition and why I was to blame. If

not, then I don’t know what I’ll do.

Truly,

I do not know what I will do

.

I. Revulsions of

the

Kyphotic

Before he could speak his father’s name,

Lucasse

needed to down a glass of cold milk and alcohol.

The combination of liquids soothed his chest, stomach, and bowels where it then

exited in a very brief but loud fecal exorcism. During that process, he was

able to utter the word that was the closest thing to a curse that was ever

expelled from

Lucasse’s

lips.

“Maurent.”

There. He said it. He spoke it into the broken air. He spoke

it into the corner of his room, the corner where the wallpaper was stripped

away by the insects and where layers stains of unknown origin combined to form

abstract pornography.

Lucasse

waited.

He waited for no specific result, no specific end to his ongoing

turmoil. Every incident in the past had been different, every result a separate

personal cataclysm independent from the last yet related by a similar set-up:

the

milk and alcohol ritual

. An outsider would not have thought each episode to

be linked but

Lucasse

knew better. He knew the truth.

Or rather the truth he wanted to believe: that his father’s

eyes would come back to look after him.

For years

Lucasse

had been a

guest in his Aunt

Eurice’s

home in a town he had

never heard of before coming to visit. The name of the town was generic and one

Lucasse

had a difficult time remembering. In fact,

there were times he had suspected the town did not even exist prior to his

arrival as if it had been invented simply to accommodate his needs.

Lucasse

normally

shrugged off that arrogance until the next time he took a walk around the town

and felt that same feeling of

newness

that was out of place in a town that looked so ancient, so colonial. Most of

the buildings were supposedly built two centuries ago yet they held a fresh

presence, an almost psychic weight of modernity that should have been alien to

such structures.

Lucasse

had once taken a walk through a small patch of woods that

led to a large farm house. Nothing seemed peculiar until he walked alongside the

house and felt a severe pain in his temple. At first he thought it was the

sunlight piercing his eyes but realized the sun was hidden by a bulbous cloud

like a child hiding from its mother. As the mystery of the pain swirled in his

head, all sounds of nature ceased. It was then that

Lucasse

knew it was the house itself that had somehow struck him. It was the house that

was telling

Lucasse

it was not what it seemed to be.

It was not an old house despite its appearance and its half-page of faux

history in the brochure available at the town hall. Through the giving of pain

it was spilling its ancient secrets, a newborn revealing its true nature

through anguished howling out of a mouth of blood. The house was a cranky

newborn made of wood and paint and its primal cries had pierced

Lucasse

, causing the pain in his head. After walking around

to the back of the farmhouse, he decided to knock on the door to see if anyone

lived there who could provide him with answers. If they couldn’t offer that,

then maybe they’d give him a drink of water or perhaps, if they were liberal

about such things, a small drink of alcohol.

Three knocks on the door brought nothing but a wind chime’s

weak song despite his feeling no wind.

Lucasse

opened

the screen door and stepped into the porch. It smelt of moss and blown-out

candles. Magazines were strewn across the floor. All of the titles had been

cleanly cut off with a razor.

Lucasse

crouched down

to pick one of them up but found it stuck to the floor by a yellowish gummy

substance.

He wiped his fingers on his shirt and stood up.

The door to the interior of the house opened on its own,

revealing a tenebrous chamber that was nothing like the inside of any house

Lucasse

had ever known. It was more like what he imagined a

stomach of a whale would look like: humid, dank, and dark with swollen shadows

that moved in waves.

“Hello?” he said to the blackness.

No voice answered. There was only the chimes again, brief

and weak but sinister in a way only soft sounds could be, like the footsteps of

a home invader or the sharpening of a butcher’s blade.

“Anyone here?” he said. “I was just wondering if I could

have a drink. I’ve been walking for a long time.”

No answer.

But the shadows at the heart of the room started to spread,

making everything darker.

Lucasse

didn’t think that

was possible: shadow within shadow within shadow within an even darker shadow.

An infinite black.

Then he found himself lying on the couch with an icepack on

his forehead.

“Where am I?”

A voice from behind him said, “You’re home.”

It was his Aunt

Eurice

. This was

her

house.

The shadows above him swayed with the sound of chimes.

“I’ll show you to your room,” Aunt

Eurice

said.

That is when

Lucasse

fell asleep.

II. Once When the Sky was Outnumbered

There was only one park in town and Roux spent most of his

time there. Though some citizens enjoyed taking walks, flying kites, or playing

with their children, Roux could usually be found in the park reading a book on

one of the wooden benches.

Before leaving his house to go to the park, Roux would run

his hands along his many shelves and take a book at random. He needed it to be

random. In fact, every night he rearranged the books on the shelves while

keeping his eyes closed. Making decisions was difficult for Roux and so he

decided to let chance dictate what it was that he read.

Book reading was not the only thing chance dictated. Roux’s

meals were chosen at random from random menus from various eateries that

delivered to his home. Roux did not want to have the responsibility associated

with such decisions. If a decision was poor, he’d rather be angry at the

silent, allusive god called Chance than at himself.

On this particular morning he was sitting on a bench

reading a book on the history of industrial parks. He hadn’t even remembered

purchasing the book yet he must have since it had been sitting on his shelf. He

had never received a book as a gift even when he had family who would be so

inclined to present him with such an item. Roux concluded he must have bought

it during one of his rare book-buying binges during which he would grab the

first few books from a random shelf and pay for them in a frantic display of

monetary irresponsibility. Still, he was surprised he hadn’t remembered

bringing such a title home. Oh well, he thought, it was surely just as good as

the rest of them.

It wasn’t a particularly sunny day nor could it really be

considered cloudy. It was, Roux thought, somewhere in between the two. The air

was neither warm nor cool. It was as if the air came from a yet undiscovered

season. No wind blew through the park; it was a morning of stillness and Roux

was terrified.

He looked down at his book. The words on the page were

jumbled. They were begging for wind, begging for something to move it away from

Roux’s hands which were too smooth, too unused. The letters, which were

previously all English, had somehow been transformed into insidious shapes and

sigils foreign to any alphabet Roux had ever seen.

Roux knew the book wanted to disown him. It had altered

itself (or had let itself become altered by some outside force invisible to

Roux) just to distance itself from him. The book had become an outsider in his

hands.

Or, Roux contemplated, it had made

him

the outsider.

There were other people in the park and Roux knew they were

trying to hide their suspicious looks.

He also knew one of those people was going to kill him.

How he knew this, he didn’t know. It was a question Roux

could not or would not answer. If the explanation was there inside his mind it

was hidden under some unconscious blanket of fear and self-illusion. It was a

truth worth hiding from his awareness. It was not a truth that was going to

manifest itself like some quant introspective epiphany. Roux simply knew that

someone in the vicinity of the bench was going to extinguish his life right

there in the park.

But he also knew he could not

leave

the park.

Leaving would upset things, upset the order that had been

predestined by whatever powers moved destinies around like shells in a

confidence game. Roux’s fate was sealed in a windless park with a book no

longer readable while he was surrounded by people who looked upon him like a

pariah. Perhaps they were right in their judgment. Perhaps he was something to

be shunned, feared, and slaughtered. Perhaps he was, as he knew some people

referred to him as, the “freak on the bench.”

Roux had never considered himself a friendly person or even

minimally a social one. His interactions were always brief and without

ceremony. He could not remember the last time he had sincerely wished someone a

“good morning” yet he could remember dozens of times within the last month in

which others had wished him that very thing. His lack of social skills had long

ago ceased to bring guilt but he sometimes regretted not being successful in

trying to

avoid

those interactions so that he would not have to meditate

on his obscene lack of conformity.

And perhaps now the chickens were coming home to roost, as they

say. He was finally going to reap the rewards of his lifestyle: his complete

and utter aversion to being

bothered

.

Roux’s eyes perused each potential assassin in the park.

There were two sets of grandparents with their boisterous spawn-of-their-spawn.

Could it be them? That would be a nice trick, sending out the least

intimidating murderer. Oh, but that would be too obvious, wouldn’t it? No, it

was unlikely to be the grandparents. They were too old; you couldn’t count on

them to move quickly enough.

But could it be the grandchildren?

There were five of them. It was difficult to tell their

ages but Roux thought two looked under three years old while the other three

looked to be between ten and twelve, a suitable age to contemplate killing

someone like Roux. Children that age often could not separate fantasy from

reality and could make very capable assassins. Yes, it could very well be one,

or more, of the children.

He wondered how he would react if it was indeed one of

them. Would he embrace death at the hands of a child? After all, who better to

exact judgment upon him then a person who is innocent and full of hope and

potential? They would simply be making room in the world by snuffing him out.

Would they actually comprehend their actions? Would they think it was all a

game and that Roux’s death was simply the end of the round? Would they expect

him to get up after they had plunged a knife (or pulled a gun’s trigger) and

caused his extinction? Roux wondered all of this and found himself even more

frightened than before. Youth had never seemed so terrifying.

He looked back down at his book.

He was on a new chapter but could not read it due to the

previous transformation. To compensate, he imagined it was a chapter about the

distribution of goods and how that affected building types in industrial parks.

Some of the foreign words were fading on the page while others were blinking to

an unknown rhythm. Perhaps they were signaling the return of some wind which

would come by and rescue the tome from Roux’s hands.

He wished that was not the case. Despite the danger he knew

he was in and the obscurity of the words, he still wanted to read, still wanted

to finish the book he had chosen at random on the shelves he had set up

randomly the night before. If he was to die before reading the book, he would

feel incomplete. Death itself would feel incomplete.

Death would feel

unfair

.

Roux figured if he was patient and accommodating despite

his terror, then maybe things would work out in a complete way.

There was a sound behind him, something that resembled the

rustling of leaves. Had the wind returned? Roux looked over his shoulder

quickly as if the sound had startled him even though it had not. A part of him

wanted to startle the wind so he may have the upper hand in the proceedings.

But it was not leaves being scattered by the wind. It was a

young mother with her child. The child, a young girl of about five years old,

was taking small toys out of a plastic bag. That it is the sound Roux had

heard: small hands grabbing for toys in a plastic bag.

It reminded him of

his last surgery. The doctors had searched through his body looking for

something, anything, to justify his excruciating pain and their extravagant

fees. According to them, they found nothing. That didn’t prevent them from

billing Roux in the amount of four-thousand dollars and eighty-three cents

which was approximately four-thousand more dollars than Roux really had to

spend.