No Joke (11 page)

Authors: Ruth R. Wisse

A lawyer taunts the rabbi with a mock predicament: if the wall between heaven and hell collapses, which side

should bear the cost of reconstruction? The rabbi replies: justice favors those in heaven, given that the fires of hell destroyed the wall. But the smooth-talking lawyers in hell would probably win the case.

15

It goes without saying that the conservative purposes served by this wit were turned by opponents of the rabbis against what they took to be the absurd logic chopping of its practitioners.

In his study of jokes, the philosopher Ted Cohen highlights a special category of

hermetic

humor, which is accessible only to those versed in an arcane subject.

16

Much rabbinic, or “yeshivish,” joking likewise rewards only insiders and shuts out Jews (let alone non-Jews) who are insufficiently steeped in Talmudic culture. The following joke's punch line is visual:

At the height of a pogrom [a standard opening for modern Jewish joking], drunken thugs break into a house of study and make a rush at the boys who are at their prayers. When one of the thugs raises his axe over a yeshiva student, the intended victim utters the prayer for

kiddush hashem

âsanctification of the Holy Nameâsaid by someone about to be killed for his faith. Momentarily spooked, his attacker demands that the other yeshiva boys tell him what his victim is saying. With lips compressed, they mutely motion the killer to continue what he is doing.

17

Even supposing that listeners appreciated this subspecies of gallows humor, the person who laughs at the unspoken punch line would need to know, first, that Jewish law prohibits a blessing uttered in vain (

brokheh l'vatoleh

), and second, that

one may not speak between the utterance of a prayer and its fulfillment. That obedience to these requirements would here result in the boy's murder is the morally absurd twist that scares up the laughter.

The familiar theme of this joke is the Jews' predilection for compounding the trouble they are in, but since part of the pleasure of jokes is intellectual, its hermetic nature heightens the pleasure of those who get it. In another version of the same story, a circumciser who is past his prime pronounces the blessing for circumcision and then mistakenly cuts the hand of the person holding the infant boy. When the man yelps in pain, the circumciser moans, “Oh, woe! A brokheh l'vatoleh!”

Those familiar with Yiddish jokingâor for that matter, with any kind of male jokingâmay marvel that I have scanted eroticism and sex. Were these Jews so chaste, so observant of the commandments of modesty, that they avoided what dominates humor elsewhere? Yes and no. One evening in the 1970s when I dropped in to visit Professor Khone Shmeruk in Jerusalemâsuch visits were among the favorite evenings of my lifeâhe and several guests who had assembled earlier, all male, were gathered around a thin book that they rapidly put away when I entered the room. Their schoolboy gesture piqued my curiosity. At my insistence, Khone later showed me Ignatz Bernstein's collection of Yiddish sayings, only not the huge classic volume with which I was familiar. It seems that in an effort to satisfy both his scholarly obligation and sense of propriety, Bernstein issued a separately published edition of erotic and scatological material.

Wouldn't you know that among all of Bernstein's efforts, this offprint

alone

has been rendered into Englishâthough not

everything turns out as funny in translation.

Vayber haltn, vos es shteyt

is rendered in English as “Women grasp what stands,” but the Yiddish expression “as it stands” ordinarily applies to the text of the Bible.

Fraytik, iz der tokhes tsaytik

, “Friday, and the behind is ready,” conflates the alleged custom of spanking Jewish elementary students on Fridays (so that they will behave over the sabbath) and prescribed pleasures of intercourse for the sabbath.

18

Anyway, you get the idea. Yiddish humor ventures into common male territory, but perhaps with more than the usual compunction. This is reason enough for me to honor the Yiddish scholars' tact.

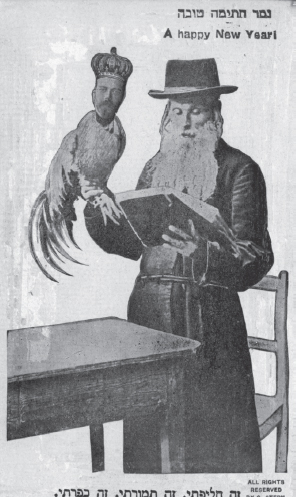

This New Year's greeting card shows a Jew reciting the blessing of

kaparoth

before Yom Kippur: “We ask of God that if we were destined to be the recipients of harsh decrees in the new year, may they be transferred to this chicken in the merit of this mitzvah of charity.” The atonement fowl would then be ritually slain, and its equivalent value given as charity. Nicholas II's face superimposed on this impending sacrifice would have amused Russian Jews in New York, where the card was printed, and recipients in Russia, if censorship did not intervene. Rosh Hashanah Postcard. © C. Stern. Russia, Early 20th Century. Collection of Yeshiva University Museum.

Women's or Folk Humor

Women's or Folk Humor

The masculine realms of Yiddish humor that I have been describing were complemented by a fourth, largely female domain where Sholem Aleichem claims to have gotten his start. As I mentioned earlier, in his autobiography he presents an alphabetical list of his stepmother's curses as his first literary work. The inventory keeps getting funnier, as common slurs like donkey, fool, and idiot cascade into lists like this one for the letter

pey

:

paskudniak

(nasty man),

partatsh

(bungler),

parkh

(scab head),

pustepasnik

(wastrel),

pupik

(belly button),

pipernoter

(viper),

pletsl

(small pastry),

petelele

(buttonhole),

pempik

(fatso),

pere-odm

(savage), and

pritchepe

(quarreler or sponger). Torrential diatribe may not be experienced as funny by its target but certainly makes for great comedy at secondhand.

Though Yiddish cursing was by no means the exclusive preserve of women, the culture ascribes to them a special talent for verbal abuse. This can range from simple expletives, like

a shvarts yor af dir

(“may you have a black year”âa year of misfortune), to such ingenious maledictions as, “May you lose all your teeth, except the one that torments you,” or (to a man), “May you grow so rich that your widow's second husband never has to work for a living,” whose pretzel twists show off their comic invention over and above the insult they deliver. With less formal education than men, women may have developed more freewheeling oral aggression. Men were wont to say that a hen that crows, a Gentile who speaks Yiddish, and a woman who studies Torah are not good merchandise.

19

Perhaps, then, as a way of getting even, the woman with “nine measures of speech” became a staple of Yiddish folklore, and the harridan housewife an archetype of Yiddish theater. The latter tradition was still going strong in the Yiddish-accented, tough-talking Bessie Berger of Clifford Odets's perennial U.S. favorite,

Awake and Sing!

(1935).

Women were also masters of proverbs, compressions of folk wisdom often adapted from classical Jewish texts or neighboring cultures. So highly did my mother value what she called

her

maxims that she left a handwritten list of them for each of her children under the heading “My Philosophy of Life.” Her register included both Talmudic homilies like

a rahmen af gazlonim iz a gazlen af rahmonim

(kindness to the cruel is cruelty to the kind), and takeoffs on Talmudic sayings. Thus, “The world rests on three thingsâlearning, prayer, and acts of loving kindness,” becomes, in her ironic rendition, “The world

rests on three thingsâmoney, money, and money.” Where others might say, “Don't worry. It'll turn out all right,” my mother would say, “Either the landowner will die or the dog will croak.” This last punch line was the rabbi's reply to the question of why he had gambled his life on his ability to teach the landowner's dog to speak within the year. A recipient of this folk wisdom was expected to know the joke and hence to appreciate the ambiguity of my mother's reassurance.

20

Sholem Aleichem plundered this long-standing treasure trove of invective and folk wisdom in fashioning his female monologists, like the distaff side in the husband-and-wife exchange of letters that constitutes his epistolary novel

The Letters of Menahem-Mendl and Sheyne-Sheyndl

. Menahem-Mendl, setting out from his native Kasrilevke (as we have seen, Sholem Aleichem's fictional paradigm of the Jewish shtetl) to make his family's fortune in the big city Yehupetz (modeled on Kiev, from which most Jews were barred), ricochets from one entrepreneurial or investment scheme to another, failing every time and rebounding after every failure. Critics have been undecided as to whether he personifies the indomitable Jewish messianic spirit or a parody of capitalism run amok, but there is less disagreement over the conservative nature of his long-suffering wife, burdened with children and the need to feed them. Where his letters abound with the new terminologies of the stock market, real estate, and brokerage, Sheyne-Sheyndl, buttressed by her ever-present mother, conveys a single message: cut your losses and return home. Her weapons of choice are her mother's proverbs. “My mother says dumplings in a dream

are a dream and not dumplings.” “The best dairy dish is a piece of meat.” And more:

No one ever made money by counting on his fingers. You know what my mother says, invest a fever and you'll earn consumption. Mark my words, Mendl, all your overnight Yehupetz tycoons will soon by the grace of God be the same beggars they were beforeâ¦. I tell you, if a mad dog ate my heart, the creature would go crazy.

21

We encountered this mad dog earlier in Agnon, and will do so again with humans or animals going mad.

What Yiddish Signified

What Yiddish Signified

Yiddish humor was no less affected than its German Jewish counterpart by the Jews' encounters with modernity, but Yiddish speakers experienced its paradoxes in

their

language, which retained its Jewishness as they shed some of theirs. The linguist Max Weinreich called Yiddish “the language of the way of the Shas,” with Shas being an acronym for the six tractates of the Mishnah that form the core of the Talmud and thus the basis of rabbinic Judaism. Why else but to perpetuate a distinctive Jewish way of life would Jews have created a separate language, and how could that language fail to preserve some imprint of the idea of divine election and Torah imperatives, the hope of return to Israel, categories of kosher and treyf, sabbath and weekday, and so forth? Yiddish signified, in however attenuated a form, Judaism's many habits of mind and conduct.

While anti-Jewish humor mocked telltale accents of Yiddish as the mark of the Jew, Jewish humor mocked the attempts of Yiddish speakers to disguise it:

A wealthy American Jewish widow, determined to rise in society, hires coaches in elocution, manners, and dress to help her shed her Yiddish accent and coarse Jewish ways. Once she feels ready, she registers at a restricted resort, enters the dining room perfectly coiffed, wearing a basic black dress with a single string of pearls, and orders a dry martiniâwhich the waiter maladroitly spills on her lap. The woman cries: “Oy vey!âwhatever

that

means!”