No Lifeguard on Duty: The Accidental Life of the World's First Supermodel (10 page)

Read No Lifeguard on Duty: The Accidental Life of the World's First Supermodel Online

Authors: Janice Dickinson

Tags: #General, #Models (Persons) - United States, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Television Personalities - United States, #Models (Persons), #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Dickinson; Janice, #Personal Memoirs, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women

right out and told me he thought I had “international”

appeal. He was also a perfect gentlemen, which I hadn’t expected; I had heard countless horror stories about the French Mafia, the group of Parisian photographers who were very hot at the time. They thought of themselves as

“street” guys. They were into their 35-millimeter cameras and liked shooting outdoors with minimum fuss,

kamikaze-style. They liked movement, action, acting. They didn’t like mannequins. They prided themselves on being the exact opposite of the Irving Penns and Helmut Newtons and Richard Avedons of the world. And they all had major attitude about it.

But not Patrice. Of course, as it turned out, Patrice was from the

south

of France—which explained it. Parisians in general are real snobs, and Parisian men are the pits. Trust me. I also discovered that I wasn’t Patrice’s type. His type was Jessica Lange, who happened to be his girlfriend at the time.

Patrice was incredibly good to me. And his photographs were little gems of discovery. They went beyond the surface shit—beyond lips, legs, and crotch to my

energy.

The shots we took together found a prominent place in my growing portfolio. Later, they would change the course of my life.

One night, Patrice invited me to join him and Jessica Lange for dinner. Jessica wasn’t just a top model; she’d already made a name for herself in

King Kong.

She was a sweetheart, and he was crazy in love with her. He called 64 J A N I C E D I C K I N S O N

her

cherie

all night. Made sure she had enough to eat and drink. Made her feel loved. Every few minutes he’d take her hand and kiss her under the wrist, as if he were Gomez, from the Addams Family, and she his very own Morticia.

I told them all about Ron, who was in New Jersey with the band. We all agreed that love was a beautiful thing.

A few days later Wilhelmina sent me over to see another photographer, Mike Reinhardt. Like Patrice, he was part of the nefarious French Mafia—this despite being the American-born son of German parents. He was shooting a lot of stuff for

Glamour,

working with top girls like Patti Hansen, Beverly Johnson, and Lauren Hutton.

“All the girls love him,” Wilhelmina warned me. “So don’t be stupid.”

I got to his studio and an assistant let me in and introduced me to Mike Reinhardt. He nodded, barely acknowledging me, then crossed the room and picked up the phone and called someone and reamed him out. He was very

handsome. And solidly built. He saw me studying him, said he’d be with me shortly, then went off and busied himself in another room.

I sat there for forty-five minutes, getting increasingly pissed off. There was a copy of

People

on the couch, and I started flipping through it. The magazine was new on the market. American’s love affair with fame was under way.

And God, did I want to be part of it! I looked at some of the faces and thought,

I’m as beautiful as they are. And I

can be shallow, too.

Then I noticed a portfolio—some of Mike’s recent

work—and looked through it. He was good. The photographs were natural, the lighting soft. And the models all looked as if they were about to ask you to fuck them.

Maybe they were.

N O L I F E G UA R D O N D U T Y 65

Mike reappeared once or twice, made some more calls, ducked into the kitchen for a bottle of Perrier, rolled a joint, smoked it, rearranged the lights, looked for a lost wide-angle lens—everything but acknowledge my existence. I felt like part of the furniture. Finally, as he walked past me for the tenth time, I tripped him.

“Remember me?” I said. He looked at me as if he were trying to place me.

“Yes. Of course. Why don’t we get started?”

He spent the next two hours testing several new lenses.

He never spoke to me. Didn’t even say good-bye. But of course: I was a nobody. I was never going to be one of the

People

people. He made me feel meaningless, unimportant, ordinary. Some day, I swore, I’d make that arrogant bastard pay for his rude behavior. And I did. But I’m getting ahead of myself here.

ªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªªª

I celebrated the New Year in Las Vegas with Ron Levy.

B. B. King and the band had a gig at the Hilton. Nineteen seventy-four had come and gone. I had moved out of the Gralnicks’ Upper East Side co-op and into an apartment on 14th Street and Fifth Avenue that Ron and I had found together. The building looked nice—it had that redbrick thing going—but the place was a little funky. And there were some pretty sleazy characters around, including a psychotic drug dealer just down the hall.

Of course, I didn’t care. I was crazy in love with Ron by this time, and he with me. And, no, it wasn’t just about the unbelievable sex. Ron wanted to be around me all the time.

He practically cried whenever he had to hit the road with the band. He called me every day, at unimaginable hours, to tell me he missed me, and that he was crazy about me, and that I was the best thing that ever happened to him. To be wanted like that—you have no idea what it did for me.

You’ll never amount to anything.

That’s the message my father had pounded into my head since I was a child.

But here was a man who loved me. Me, Janice, a little nineteen-year-old nobody, struggling—like ten thousand other girls—to make it in the Naked City, and he loved me just the way I was.

A few weeks after we came back from Las Vegas, Ron

N O L I F E G UA R D O N D U T Y 67

took me out to Brookline, Massachusetts, to meet his parents. I was so nervous we had to park a block from the house until I could pull myself together. Anxiety Dickinson indeed!

It was a beautiful house on a tree-lined block in the ritziest suburb I’d ever seen. His parents met us at the door, and hugged me as if they’d known me all their lives. Ron had obviously told them all about me.

His father, Joshua Levy, had invented some kind of plating process that NASA took to the moon. He was gentle and very refined. “Hey, Dad,” Ron said. “Look at this beautiful little bird that flew all the way up from South Florida.”

Ron’s brother, George, was also there. He was quiet and warm and—like his parents—went out of his way to make me feel welcome.

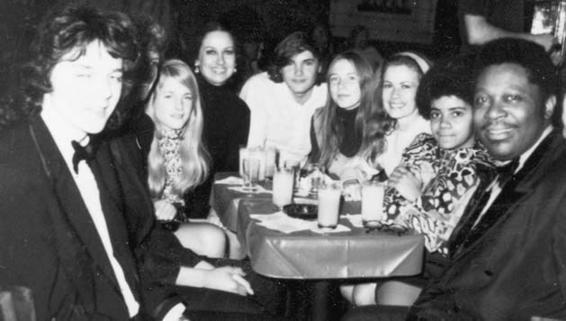

Best of all, however, was Ron’s mother, Jeanne. She had the most beautiful, chestnut-brown hair and the same sparkling green eyes as Ron. She also had a wonderful RON LEVY (FARTHEST LEFT) AND B. B. KING (FARTHEST RIGHT).

JEANNE LEVY IS FOURTH FROM THE LEFT.

((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((

68 J A N I C E D I C K I N S O N

laugh—more of a cackle, really—and I couldn’t get

enough of it.

She had strong opinions, too. Over dinner, she told me she hated Ron’s lifestyle. “He’s wasting his talent on B. B.

King,” she said. And there was no denying his talent: People in the business said he was the best white blues piano player around—even if he couldn’t read a stitch of music.

“He should be at Juilliard, studying to become a real musician,” she said.

Ron protested from time to time, but he was smiling. It was obvious he’d been through this many times before, and he seemed to find it kind of amusing. From time to time, he’d look over at me and wink,

That’s my mother.

She didn’t approve of his drinking and smoking, either.

She meant the

cigarettes,

of course; she didn’t have a clue about the pot. And the

notion

of cocaine wouldn’t have entered her head.

My nice little boy?

Me? I wasn’t big on pot, but every now and then I

enjoyed a line or two of coke. Mostly, though, I was into Courvoisier in those days: Courvoisier with O.J. back.

A week after we returned to New York, Ron had to go on the road again.

“Why don’t you come with me?” he said. We were in

the apartment on 14th Street. We could hear someone coming up the stairs, en route to the drug dealer’s. Ron bent over the table and snorted another line. “It’s only Ocean City,” he said. “Right down in Maryland. There’s plenty of room on the bus.”

I refilled my cognac snifter with Courvoisier, nurturing a pleasant buzz. “Okay,” I said. “If you don’t think B.B.

will mind.”

We left the next afternoon. The bus was so thick with smoke you couldn’t

not

get stoned. It was a hoot. B.B. kept N O L I F E G UA R D O N D U T Y 69

smiling at me and Ron and shaking his head. “Man, you two,” he said, grinning his big warm grin. “I smell trouble.”

He meant it in the nicest possible way. Or so I thought.

Ron and I couldn’t get enough of each other. We made love around the clock. The night we reached Ocean City, I did a little striptease for him in our hotel room. I was flying. He was flying. “Oh, baby,” he kept saying. “Oh, baby, baby. Oh baby, I love you so bad.”

The next night Muddy Waters showed up for the show

and stayed long after the last member of the audience had gone home. He and Ron and I and a few of the band members and their girlfriends were sitting around, chatting and riffing and getting stoned. And Muddy told a very funny story about how to sing the blues.

“Well,” he said. “If a song begins with ‘Woke up this morning,’ that’s the blues. Especially if you repeat the line.

And if it’s about a woman, and she’s a nice woman, that’s

not

the blues. But if the woman’s mean as a rattlesnake, and ugly as a junkyard dog,

that’s

the blues.

“If you’re young you got no business singing the blues,”

he said, “because you ain’t fixin’ to die. Only ole people can sing the blues. You got to be older than dirt. But if you’re young, it’s best to be blind. Or maybe you shot a man in Texas or Memphis. Or maybe you’re missing a leg. But you can only sing the blues if a alligator got your leg. If you lost your leg in a skiing accident, that ain’t the blues.”

Muddy bent over the mirror and a huge line of coke

leapt into his left nostril. He looked a little dazed for a moment, then turned his eyes on me. “Janice,” he said.

“Can you sing the blues?”

“No,” I said. “I’m not mean as a rattlesnake.”

Muddy laughed. “You can sing the blues, woman. Body like that, you

gotta

know how to sing the blues. You be exonerated, girl.”

70 J A N I C E D I C K I N S O N

They jammed for a while. People drifted in and out of the place. We killed a couple of bottles of Courvoisier.

Hours later, Muddy turned to me again and

insisted

I could sing.

So I said, “Well, I’ll try anything once.” I was young and stupid in those days. And very drunk at that moment.

Muddy plucked his guitar and I recognized the tune and got to my feet and sang: “Take me to the river and wash me down / Take me to the river and put my feet back on the ground.”

Everybody cheered when I was done. I guess they must have been pretty stoned. The only ones who didn’t cheer were the bums who were passed out all around us. On the floor. On the couch. By the edge of the stage.

“Well, you didn’t wake none of them up,” he said.

“Is that a good thing or a bad thing?” I wondered.

“

I

think you can sing, Janice. And I’m Muddy, so I must know.”

One Sunday morning, about a month after the Ocean City trip, Ron and I were sitting in the claustrophobic kitchen of the 14th Street apartment, nursing coffees, trying to plan the day ahead. I had a little Courvoisier-and-coke hangover. He didn’t feel all that good himself. He kept saying drugs were evil, a duplicitous bitch; he was going to quit once and for all.

He looked at me, his other bitch, the less evil bitch. And he flashed a mysterious smile.

“What?” I asked.

The smile just wouldn’t quit.

“I’m thinking,” he said.

“A thought of yours would die of loneliness,” I said.

He laughed and had another sip of coffee and looked up at me and the smile disappeared. “Janice. Baby. I. Was.

N O L I F E G UA R D O N D U T Y 71

Wondering . . . ” The words came slow and heavy. He was making me nervous. Then he blurted it out: “How would you feel about marrying me?”

We were married in his parents’ living room, in front of the fireplace. It was a small affair. Just family. Along with a rabbi, of course, and a minister. The rabbi was a friend of the family, and the minister was the rabbi’s idea: For some reason, he thought he wasn’t legally able to marry a

shiksa

.

Okay, that was the weird part. Here’s the

really

weird part: My parents came to the wedding. Yes, it’s true. My mother and the rat bastard showed up.

And the oddest thing of all: Shortly after Ron proposed, we came back to Brookline to tell his family. His mother was elated. The next day she and I went out and did girl stuff in town. Shopped. Had our nails done, side by side.

Ate lunch at her club. Like that . . . I was floored. I felt so close to her. I found myself wishing that

she’d

been my mother, instead of the mother I had. And on the way back to the Brookline house I began to cry. She pulled over and asked me what was wrong. I couldn’t hold back. I told her everything. I honestly couldn’t help myself. I told her things I had never told anyone in my life.