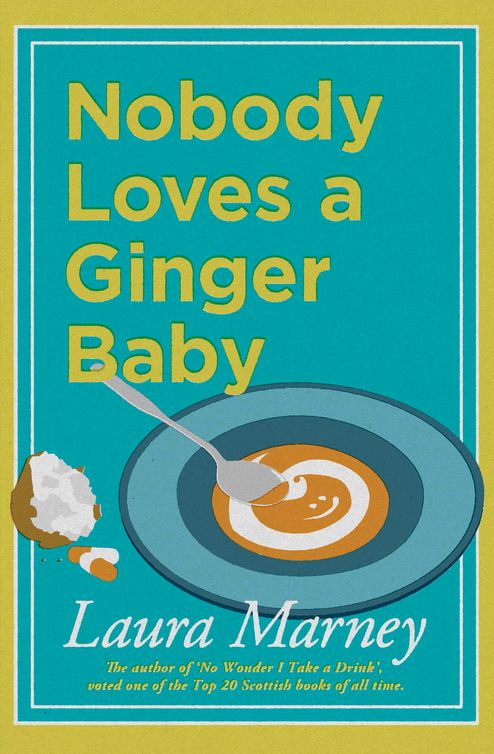

Nobody Loves a Ginger Baby

Read Nobody Loves a Ginger Baby Online

Authors: Laura Marney

Laura Marney’s first novel,

No Wonder I Take a Drink,

was voted by the public in

The List

magazine poll as one of the Top 20 Scottish books of all time.

“At last, a funny novelist with guts.” – Henry Sutton,

Mirror

“Marney gives chick lit a shot of adrenalin with a novel featuring one of literature’s most repulsive love objects. Hard core romance for the bitter and twisted.” –

Independent,

50 Best Summer Reads

“Nobody Loves a Ginger Baby

has a very wide appeal, from teens upwards… Marney shows rare insight into the human condition, and her unique style and wit have the reader laughing out loud one moment and incredibly sad the next. She manages to offset the gruesome reality with some sparkling banter. Some scenes are hilarious. Her writing, however dark, is immensely energetic and a real breath of fresh air.” – Jacqueline Wilson,

Bristol Evening Post

“Laura Marney has followed up last year’s debut by surpassing it. Like its predecessor,

Nobody Loves a Ginger Baby

is endlessly witty and good-natured… Marney has introduced a darker tinge to her writing without relinquishing an ounce of her charm… Throughout, [she] is brimming with confidence as she explores her range.… Do not miss out on Laura Marney.” –

Glasgow Herald

“The obtuse and faintly ridiculous is transformed into a hilarious edgy satire by a Scottish writer who has such a gift for dark humour that her books have a heady whiff of Christopher Brookmyre

without

the body count.” –

Scottish Daily Record

“Glasgow author Laura Marney in dizzying form. Effortless prose and solid characterisation… Her language is inherently local but never forced, and her people require little introduction, such is the author’s talent for conveying personality. The result is an honest, rounded and enviably simple novel that feels wholly organic in its unfolding.

Nobody Loves a Ginger Baby

makes for a perfectly lovely relationship drama.” –

The List

A GINGER BABY

Laura Marney

To Holly, Max and Ellen,

for making me laugh and making me proud.

Praise

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Epilogue.

Reading group questions

Why I wrote Nobody Loves a Ginger Baby

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Also by Laura Marney

Copyright

‘No,’ Daphne tells Donnie, ‘stop worrying, I’m not going to chuck you.’

This is what she tells him to calm him down. It’s not always what she thinks.

‘But,’ she says, only half joking, ‘you’d better step up your

antidepressants

. You’ll get arrested if you don’t get a grip on the kleptomania and there’s a good chance you’ll be sacked when they find out who’s putting soap in the sandwiches. You could even get evicted from your flat. I’m pretty sure squirting a piss-filled Super Soaker, even at deserving neds, is an evictable offence. Take your meds,’ she gently encourages him. ‘You don’t want to be forcibly committed, you’ll end up licking the windows in the laughing academy.’

Laughing academy, they both laugh at that one.

On the outside Donnie looks like an ordinary Joe, he isn’t overly tall or handsome or different in any way. He wears his red hair short and tidy. He has two eyes, two ears, a nose and a mouth, all of average dimensions, all precisely in the right place. If he is exceptional it is in his symmetry. The second and fourth fingers of both his hands are exactly the same length.

If you walked past him in the street you wouldn’t notice him, even a street where there were no other passers-by. If, on that same deserted street, Donnie walked past holding a smoking gun and a swag bag filled with pilfered sporting goods and novelty items, you’d be hard pushed to pick him out in any subsequent identity parade. He is very, very careful to be discreet; he is devious. This reticence extends even within his employment, which Donnie

thinks of as his job rather than his career. He’s good enough at it and that’s good enough for him.

Apart from the men he plays football with Donnie has no friends of his own. With Daphne’s friends he is polite, considerate,

charming

. They think he’s a great guy. Little do they know that when, in the privacy of their own homes and after a few drinks amongst friends, they say and do foolish things, it is meat and drink to Donnie.

He keeps Daphne awake in bed by picking apart her friends’ conceits and weaknesses, ascribing ugly motives to their

good-natured

buffoonery, reprising phrases they have used intemperately so often that they become, in Daphne’s mind, her friends’ signature tunes and she has to be careful not to say them out loud. Daphne’s friend, Mark, diffidently recounts what his boss has recorded in his annual appraisal: ‘Mark Leslie is probably the most popular lecturer in the department.’ Donnie calls him ‘Carlsberg’. He asks Daphne with his imitation of the gruff voice-over of the advert, ‘Is Probably The Most Popular Lecturer In The Department coming?’

‘Probably,’ is Daphne’s tired reply.

Donnie relishes inventing cruel nicknames and using them exclusively with Daphne, like a secret code. Joe, who so often

earnestly

affirms his heterosexuality, becomes Nancy Boy. Lucy, who occasionally recounts her once-only experience of magic

mushrooms

, is known, among other things, as ’Shroomhead. Probably worst of all is his name for Colette, shy about the disfiguring scars across her chest, who never talks about the childhood accident when she was peeled from the red-hot bars of an electric fire, her young bosom permanently desiccated. He calls her Char Grilled.

Donnie is high maintenance. He’s not the type of man who can be left to himself at a party. Daphne would like to mingle but she stays by his side to keep him from becoming jealous of all the men who, given the slightest encouragement, would throw her to the floor and ravish her. She also has to guard against him visiting the bathroom and trousering their host’s cute ceramic toothbrush holder.

‘It’s Tigger off

Winnie the Pooh

,’ Donnie later tells her, giggling at his own daring, attempting to justify the theft.

Every time he has a bath he likes Daphne to wash his hair. She kneels at the side of the bath and rubs shampoo into his scalp, scrubbing around his carroty hairline. When she’s ready to rinse she supports the back of his head and lowers him under the water. The kneeling hurts her knees and tires her back but Donnie seems to love this baptismal ritual; he closes his eyes and smiles.

Every few weeks she has to shave the twizzley ginger hairs that grow on the back of his neck. They stand at the bathroom sink and he takes his shirt off. She scooshes a blob of white foam into her hands and rubs it on his neck. Daphne thinks it’s a pointless exercise; she’s the only one who ever sees this secret part of his body.

If ever she wants to make a Spanish omelette she has to make two: one to eat that evening and one for Donnie to take to work the next day. It’s a fiddly job getting the omelette in his plastic sandwich box and the box smells of garlic for days afterwards. How can he be bothered eating the same thing two days in a row? Daphne wonders. Donnie says he wants to make his workmates jealous with his home-made Spanish omelette while they eat their usual cheese, or occasionally, soap, sandwiches.

There are certain places Donnie will not go. He will not go to the theatre; theatre is ‘a pile of wank’ patronised only by poofs. He won’t set foot inside any kind of museum; museums are for eggheads. Nor trendy coffee shops; they are taking the piss charging more than two quid for a tea bag dunked in a plastic cup of hot-ish water. Although he takes a keen interest in Daphne’s

undergarments

he refuses, for fear of being branded a pervert, to enter what he calls a ‘lingeree’ shop. He doesn’t do DIY shops or clothes shops or supermarkets, except of course for Asda. Even then, the Partick branch of Asda is out of bounds because his ex-wife, who he has not seen for six years, might be in there. He can occasionally be persuaded to go to the movies but he will not watch foreign

language

films, costume dramas, political thrillers, chick flicks, rom-coms or weepies, unless there is some kind of football content.

Donnie is obsessed with football. He pays for Daphne to have cable TV installed in her flat so that he can watch matches when he comes round. He takes pride in a comprehensive knowledge of the

game and his team and laughs when Daphne calls him an anorak. He knows off the top of his head when, and by how many goals, his team has ever won a competition. He’s intimately acquainted with players’ details, their backgrounds and future prospects. He compiles databases of team statistics and applies complicated

formulae

to predict the outcome of each game. Sometimes he is right. Whenever he gives Daphne advice, for instance about one of her difficult students, it is always couched in footballing terms,

counselling

her to ‘take control of the dressing room’, or ‘show them your championship medals’. One room of his flat is virtually filled with football memorabilia. Daphne sometimes finds him there, reading from his stack of fanatical fanzines, chuckling away to himself.

But Donnie chuckling is a lot easier than Donnie panicking. With drastically reduced medication his behaviour has been wild and unpredictable over the last few weeks. It is a temporary side effect and will stop when the chemicals settle down, Daphne tells herself, but it’s embarrassing and often inconvenient.

They make arrangements to meet friends for dinner and half an hour before, Donnie decides he doesn’t want to go. Daphne has to call off with a lame excuse that she knows they can hear in her voice. So, she makes a steak pie from scratch, and, just when she is cooling the perfectly golden crusted pie and transferring the buttery mash into an old-fashioned tureen, Donnie throws up and has to go to bed. Daphne brings him tea and he lies quietly sipping, only managing to get up when

Match of the Day

comes on.

They accept an invitation to go paintballing with Daphne’s crowd. In the communal changing room the atmosphere is crazy. Everybody is talking loudly, bumping into each other, struggling into their kit: overall, chest shield and helmet, ammo belt and gun. Donnie is the first one dressed and ready to go. He produces a tube of something and carefully smears two even black lines under his eyes. One of the nicknames Daphne has given Donnie is Semper Apparatus, based on his predilection for being well equipped for every occasion. He is good to himself and spends many hours in sports shops eyeing, buying, and, when the opportunity presents itself, stealing pocket-sized products.

‘Oh yeah!’ says Carlsberg. ‘Give us a shot of your warpaint, Donnie, that looks cool.’

Donnie hands it round and now they all look cool, even Nancy Boy. The battledress transforms Daphne’s harmless pals into fierce warriors, handsome and heroic. Donnie looks especially sexy, Daphne thinks, as she imagines his face inches above hers in bed tonight. She makes a mental note to ask him to bring the warpaint.

As the instructor takes them down to the gate of the battlefield, Lucy starts a whooping rallying call and this is swiftly taken up by all of Green Platoon, as they have become. Their adversaries, Blue Platoon, a stag party of eight hung-over lads, are already at the gate. They have no enthusiasm for an opposing war cry and already Green Platoon have the psychological advantage. Striding forward, Donnie waves his gun in the air the way people do in the Middle East and the platoon follows his initiative.

After going through the tedious safety talk, ‘protective

equipment

must not be removed at any time within the war zone,’ the instructor tells both sides that the object of the game is to obtain the enemy’s flag and plant it on the hill.

Exchange of fire is at first tentative and sporadic but quickly becomes reckless. Within ten minutes Daphne is grabbed from behind and pulled into thick bushes. She believes she has fallen foul of a kidnap attempt by the Blues and struggles as hard as she can, but her captor is Donnie.

She can tell immediately that something is up. He has taken a direct hit, his breastplate is splattered with blue paint but it’s worse than that. The black under his eyes is wet, either with sweat or tears, Daphne is not keen to find out which.

‘I can’t do this, I’m just not …’

‘Oh Donnie don’t, please, not today. C’mon, we can’t let the side down; we’ve just started! So you’ve been hit, it’s okay, we’ve all been hit, I’ve been hit twice, I’m going to have a corker of a bruise tomorrow but we’re winning! I got that big baldy guy a cracker, right on his side…’

‘I’m going home.’

‘What for? What’s wrong with you?’

‘I can’t do this.’

‘Okay, relax; nobody’s making you do it. I’ll come back with you to the changing room. Get a cup of tea or something out of the machine, you can wait for us there.’

‘No. I’m leaving.’

‘But Donnie, what about Mark and Lucy, how will they get home?’

‘I don’t give a shit about Mark and Lucy, I nearly took one in the eye, it missed me by a fraction.’

‘But that’s what the helmet’s for! It’s perfectly safe. D’you think they’d still be in business if their customers’ eyeballs were regularly exploding? They wouldn’t get insurance, the council would shut them down; think about it, be rational, Donnie. Lucy and Mark need a lift, how will they get back if we leave?’

‘I didn’t say you had to leave. Stay. Enjoy yourself.’

‘How are you going to get home? We’re in the middle of nowhere.’

‘I’ll get a taxi, I’ll…’

‘A taxi?’

Everyone is gutted that Daphne has twisted her knee. It takes a few minutes to sort out alternative transport arrangements for Lucy and Mark, vital minutes on the field of battle. They wave them off as Daphne hops to the car with Donnie, who gallantly if a little inelegantly, lifts her poor twisted knee and supports her.

Although no one says it, Daphne feels like a deserter. Her

comrades

say nothing but suffer a humiliating defeat at the hands of the hung-over Blue Platoon. At college Daphne will have to wear an elastic bandage around her knee, and remember to hirple for a few days. Donnie nicknames her Gimpy. That night they have comforting, rather domestic sex. Daphne has forgotten all about the warpaint.

Donnie worries constantly that she will leave him. He talks about it all the time, more and more since he lowered the dose of the antidepressant. He mentions it at least once a day, saying she’s bound to run off with someone else.

Daphne knows she’s no supermodel but neither is she a

toothless

hag. She scrubs up well, her thick dark hair gathering in solid

clumps around her heart-shaped face. With a push-up bra she can muster quite a respectable cleavage and hip length jackets work wonders on her chicken drumstick thighs. She favours pastel shades that don’t try to compete with her high colouring: her cheeks are red and round like Santa’s and with glittering green eyes and a flashing white smile she can be as vibrant or as irritating as a fruit machine. Before she met Donnie she had always suspected, although she would never say so, that she is beautiful.

Donnie says so, he tells her so often that she now accepts it as a given. But she’s acting the innocent, he says, pretending to be unaware that men fancy her. Daphne concedes that she might occasionally encounter members of the opposite sex who are

attracted

to her, but what does he think she is?

He remains unconvinced of this argument and watches her like a hawk around her male friends. She makes an effort to be tactile with him in front of people so they get the message; so he gets the message. After sex he holds her so tight she can hardly breathe. As he kisses her neck and strokes her hair, she says soppy things to reassure him, waiting until he’s asleep before unravelling his arms.

Sometimes she thinks: wouldn’t it be nice to have a nice

ordinary

boyfriend, one who didn’t constantly harp on that he was about to be chucked, instead of one who, if he were to keep up this unrelentingly needy, greedy, craziness, might find himself chucked.

And then he chucks her.