Norseman Chief (29 page)

Authors: Jason Born

Rowtag the Younger showed his wise patience only went so far, “Hassun, don’t bring your father into this. I know that you and my father were of the same age and came to be men in the same year. He spoke only great things about you as I grew up. But you speak as one who cannot control his bowels; you shit from your mouth.” Two of the younger men burst into laughter, but the scene turned ugly as Pajack took a burning log from the central fire and thumped Rowtag. The young man saw it coming and so the blow hit his forearms, scattering embers and ash onto others who had to stand and beat the coals to avoid catching fire.

Pajack and Rowtag pounced onto one another, grappling to stuff their fingers into the other man’s eyes. I was glad that neither carried a weapon and that there was no tradition of drink among the Algonkin. If either was true, the fight may have ended with much worse than a few scratches and damaged pride.

I strode around the circle of men as they still patted out the embers. I picked both young men up by the greased tuft of hair that sat on top of their tattooed heads. Rowtag blindly landed a fist onto my knee while Pajack jabbed an elbow into my windpipe. My plan was to hold them, but they angered me as they scraped like young rabbits held by their long ears, and so I rapped their heads together twice before they settled dizzily onto their feet.

Both Rowtag and Pajack looked up into my face, seeing that I meant them harm if they did not stop their nonsense. After looking back and forth at each other, a wincing nod from each told me I could drop them back to the hard-packed earth. Soon we settled back to our places, the only indication that something happened was Pajack holding his head and Rowtag inspecting his burnt forearm.

Achak rose then, asking the group to widen to make room for another man in the circle of council. Their asses slid around until there was a spot. “Halldorr, sit with us in council today.”

I laughed at him. “You must be desperate for wisdom to seek it in me.” Most of the men laughed along with me. Hassun shook his head, sticking his chin out. Pajack frowned. “I’ve told you in the past that I don’t pretend to lead you and therefore, why would I sit in council?”

Achak answered, “It is precisely why you do not seek to lead that we, as council among your new people, insist you join us.” And then, “Hassun has rightly pointed out that we must keep with tradition.”

They had asked me to sit in their circle at least three times over the previous ten years. Each time I declined. But on that day, the day after we buried Hurit’s only son, my step-son, I agreed. Maybe it was Providence who guided me. Or perhaps it was the old chiefs whose bodies lay buried in the hillside under that tree with the roots gnarled like the Yggdrasil tree.

And so I sat next to Achak. The men nodded their approval to which I answered stupidly, “Thank you.”

“And now it would show a unified people if Hassun nominated the man who should serve as the next chief of our lands. After all, by tradition the chief must come from the council and he now sits in council,” suggested Achak.

Hassun groused and grumbled, now knowing that he had no hope of claiming the small throne, such as it was. As quickly as he could, “Enkoodabooaoo should be chief.”

Then like a dry field of wheat catches fire in late summer, each man around the council circle sparked his assent and I was named chief. I became jarl of Vinland as Leif foretold so many years ago. I was chief of the skraelings, my new people. I inherited a chiefdom from my stepson, crooked or bent as Rowtag the Younger had said. I would not be killed for making a peace with the Pohomoosh because the one who knew about such things was dead.

I was chief and sitting there with the power newly granted in me, I recalled the old saying of my first people, “A thrall takes revenge at once, a fool never takes revenge.” And so we prepared to go to war against Luntook and his Pohomoosh Mi’kmaq for the killing of Etleloo. In my mind the Pohomoosh chief and I had no agreement, no bargain, no treaty, no peace, at least not anything enforceable. He granted us safe passage, but only one of us received it. He and his kind would pay.

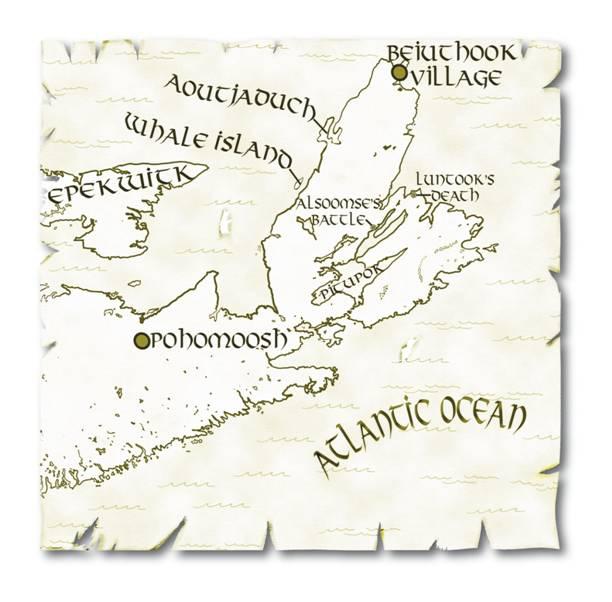

PITUPOK & SURROUNDING LANDS

PART III – Jarl Halldorr!

1,036 – 1,066 A.D.

CHAPTER 13

The bones of my naked backside seemed bent on burrowing through the thin skin of my tired ass from the inside out as I sat on the log in the sweat lodge. I was thankful that the log had been stripped of all its bark, making it a smooth surface on which to sit, but sitting there completely naked made me more aware than ever of my age. Seventy years I had roamed this earth and now I sat alone with Hurit, each of us naked, seeking some peace at the outskirts of the village.

In the years I had been with the woman, we had visited the lodge many times. Most of the time I found the occasion ripe for spilling seed into her and she was usually most receptive. I think that it was on one of those occasions when the seed that became Alsoomse found itself planted Hurit’s womb. Times had changed, however. First, her monthly bleeding became erratic until it eventually ceased altogether. When she told me what was happening to her and that it was the path of life for all women I was initially enthusiastic as I thought the woman would have no reason to withdraw herself from me for the week of blood every month. The reality proved less thrilling than my imagination.

After her bleeding stopped about ten years ago, my woman seemed to have even less zeal for our time together when I entered the space between her legs. In fact, my ribs began to receive her elbow more frequently than ever when I tried, whether with kind words or devious actions, to suggest we revisit those old times of intercourse. But the woman yet loved me and, in truth, I loved her even more than when we plowed like spring farmers.

Hurit sat next to me on the log. I grumbled to myself about the aching bones in my ass and wondered if hers felt the same. That moment was another of only a handful in my life when I made the right choice with regard to the words I offered my woman. Or, rather, the words I didn’t offer. It was probably best I did not ask, for if she was not bothered by the pain, the woman would think I called her rotund like the fat, hard-working widow who lived in the mamateek next to ours. That woman’s true name escapes me because I would always call her Njoln in the skraeling tongue when I spoke of her with Hurit. Njoln means mistress and the memory of those talks and Hurit’s resulting anger still makes me wobble with fits of laughter. That rotund woman was a good mother – she raised three children to adulthood after her husband was gored by a moose. But that day, at least, I had the sense to say nothing to Hurit and so I just grumbled to myself.

Despite our infrequent times of coming together, I still found that my manhood rose when I saw Hurit there in the sweat lodge. Her skin was moist, glistening in the dim light that snuck into the house like sets of straight spears jutting through the occasional gap in the bark covering. In truth, she was yet beautiful. Hurit was, after all, still a pup compared to me, having only lived about fifty-five summers. Sometimes I would tell her that I saw one of the younger men watch her scrape a deer hide with some lust in his eyes. She scoffed, but it was true.

The village all shared the single sweat lodge which was a small, round mamateek situated near the river bank. A single family would claim it for the times between meals on any given day. The only two families given precedence were my own since I was chief and that of Hassun who had taken on more of our shaman role as Nootau declined and eventually died. Hassun reveled in the power of his default position, but harbored bitterness toward me for taking a title he thought belonged to him.

The lodge was considered a doorway between our world and the spirit world and so Hassun was likely its most frequent occupant, sometimes alone and other times with “helpers” who were usually younger women who found themselves with child some months later. There were many times that he emerged from the little house saying that he spoke to Hurit’s son for advice. I, too, had tried to meet Kesegowaase or his grandfather, Ahanu, in the spirit world, but failed each time.

I usually tried to speak to them about the son of Makkito, Etleloo’s daughter. Within several weeks following the girls’ rescue, Makkito showed that the Fish rape had found a seedbed. Her breasts and bellied swelled. I saw the girl accepted as wife by a competent though middling man of the tribe. He took reasonable care of Makkito and raised the little bastard as his own son. The man named Makkito’s boy Chansomps which means locust. The boy, well he was fourteen and a man now, was a fighter which I deemed as good. However, he showed no willingness for sense, fighting anyone and anything until he usually lost in a bitter, sputtering rage. I supposed it had to do with how his mother found herself furrowed all those years ago. The anger she felt at the time, carried to the son. Neither of the two dead chiefs saw fit meet me in the sweat lodge to advise me on the subject.

The door of the lodge faced the river. Nearby on a stretch of flat ground we had accumulated scores of large rocks, not the fragile rocks that chip or break when struck, but the types seemingly hard as steel. After a small mid-day meal, Hurit and I made a bed of twenty stones then made a roaring fire over top of them. I spent my afternoon in council with my warriors while she tended the fire until it turned the rocks nearly orange. When my woman retrieved me, we scooped the coals and wood out of the way then I kicked the blistering, round rocks onto a hide and dragged them into the lodge. We sealed ourselves in and doused the rocks with water that was stored in a bladder hanging from a leather thong.

Hurit sang next to me that day. Her voice was good; though Gudrid, the widow of Thorstein I had so wanted to wed in Greenland, carried a tune as one of Christ’s angels and would have outshined my woman that day. I smiled and listened while the heat and steam cleansed my entire body. When she paused I sang a song in Norse to the old gods. I had sung it for her before and my woman had grown to like it, though she had only bothered to learn the meaning of several of the words.

The two of us were at relative peace then, satisfied in our lives, and I thought that perhaps that would be a day when my woman would invite my body to hers. But a rustle at the door banished those thoughts and shattered my hopes like pottery falling to the ground. “Who is it?” I asked, less than pleased, wishing Right Ear was still alive so I could sick him upon this intruder.

No one answered and the noise continued until the door I had carefully affixed from the inside, gave way and burst open, bits of bark littering the hard-swept earth. The late afternoon sun poured in, making both of us squint. Surly now, I shouted, “By the One God, I just came from council. What is so important that I cannot have a moment’s peace with my wife?”

Alsoomse, my little Skjoldmo, ducked into the lodge then and tightly closed the door behind her, even brushing the debris she had created while breaking in over to the side of the lodge. I shrugged. I would not be entering my woman that day. Of course, I had made love to my wife countless times when Alsoomse was at home in our mamateek so her presence would not have necessarily prevented the act. But I saw her mother’s eyes light up when the girl entered. Alsoomse met her look and I could see the two meant to talk about some such nonsense that drives women.

Our family had laid claim to the sweat lodge many times while my little girl grew up so I was not surprised when she pulled the cords at her shoulders and waist that bound her buckskin smock so that it slid to the floor. She had spent every day of her life with Hurit’s people and had never been instructed in the ways of modesty. I am certain that if any of my Christian brothers or sisters ever finds this writing that they will somehow be appalled at my looking upon my grown daughter’s naked body. My eyes were those of a father, however. I knew she was young, strong, and beautiful. I knew that men of any race would look on her with lust should she pass by their gaze in such nakedness. I looked on her with honor in my heart, nothing more or less.

Alsoomse, my Skjoldmo, had grown tall and strong from her years of training with many weapons of my new people behind her mother’s back. I know she trained thus, because when I found her hidden in the forest doing so several years earlier, I encouraged it and even helped with her methods or movements. Prior to my joining, the poor girl had only the bark of an unlucky tree on which to practice her craft. With repetition and my tutelage she became good at swinging the small axe, but especially excelled in the bow. The muscling in her right shoulder and across her chest, above and behind her breasts proved this fact. Hurit did not notice or chose to ignore what was in plain sight.

Alsoomse sat on a copy of the log on which her parents now sat. It was only a matter of moments before the heat released from her entry again built up in the small lodge. The girl reached for, then dumped, more water atop the hot stones so that hissing steam closed in around us.

I began to hope I was wrong and there would be quiet in the sweat lodge when several heartbeats passed without the two women talking. Hurit broke the silence. “I think we should ask your father when it will be time for you to live in your own mamateek. If you won’t take a husband anytime soon, you should at least learn how to build one on your own if a husband won’t be there for you.”

“I’ve already spoken to him about that; he says I may construct one before the snow falls this winter.” She and I had spoken. I loved having the girl in my own house, but if she was to be stubborn about accepting a husband, then Alsoomse should learn to provide for herself. That included providing a shelter. Besides it was a good time to build a mamateek for several weeks earlier we had moved the entire village to a new site, leaving many of the pests behind.

“Good. And what of a husband?” asked her mother who was beginning to feel very old and so desired to look on the faces of grandchildren. Her previous lone grandchild, the daughter of Kesegowaase, Kimi, had lived among the Pohomoosh since her capture fifteen years before. I had not laid eyes on the girl since I saw her struggling in the muck when Etleloo and I sought out Luntook. She was likely the mother of some Pohomoosh brats as she suffered in one of their shambles they called a mamateek underneath some stinking, sweating Mi’kmaq. I shook the image from my mind.

It was true that my daughter should have been married to a man of the village by now. She was past the proper age. At first, when she began to defiantly turn down would-be suitors, I wondered if she wouldn’t prefer a Norseman like her father. This small flight of fancy made me proud. I thought about leading a long expedition in a trail of canoes back to the frigid shores of Greenland to Eystribyggo to find a tall Norse warrior or farmer for her. Hurit was wary when we talked about my idea, but the thought truly melted away like frost in the morning sun when I mentioned it to Alsoomse that day in the sweat lodge.

Due to Torleik’s able instruction over the years, she had long ago surpassed my ability to converse in Norse, Latin, and the language of the Beiuthook. So I was not surprised when my once-little Skjoldmo instantly replied, “Non patrem. A mulier praegnans facit pauper miles.” I laughed even though she was correct. I clapped my hands just shaking my head for I did not care to argue with the young woman that it was universally accepted that all women made poor soldiers, regardless if they were with child or not.

Not understanding any of our talk in Latin, Hurit scolded both of us. “You two had better not be talking about me in that strange tongue of yours! If you are, I’ll see that months go by before you know me in any meaningful way, Halldorr Olefsson! And you, your father’s little Skjoldmo, I will make sure you are busy preparing for the clambake with no assistance from anyone.”

By the One God, I loved my woman. Fiery sometimes, caring others – always strong. As a pet name I began calling her Nuttah, which means “my heart” in her tongue. That love didn’t stop me from laughing at her that day, though. Alsoomse joined in, and it was only moments before Hurit was yelling at us again to find out what was so funny.

We tried to calm her, but Nuttah would not hear of it, so she rose to her feet, stepped over the steaming rocks, and burst out through the door. I heard her splash into the chilly waters of the river to rinse the sweat from her body. The steam poured out the door and soon the heat was gone, replaced by the cool air that comes between summer and winter. Alsoomse and I looked at one another, stifling laughter again, choking it down so that my Hurit, Nuttah would not be further angered.

“I hear you two in there and this confirms that you may never find yourself inside me again mighty chief!” She said the last words with angry sarcasm. I pushed my hands down on my knees to help me up, hearing a resounding set of pops in my left leg from both its knee and from some sinewy tendon which had begun twanging like a bow string around my old spear wound whenever I bent the leg in such a way. Ducking out the door, I chuckled silently, knowing that the anger Hurit now felt could be channeled into passion later and I now had the best chance in weeks of being with her. Alsoomse followed and soon our entire family was wading in the cold waters as we had for years.