North Yorkshire Folk Tales (8 page)

Read North Yorkshire Folk Tales Online

Authors: Ingrid Barton

Wolfhead staggered back with a howl and began to paw at his nose. The girl tried to struggle to her feet, gasping for breath but before she could rise the giant was standing over her, his face full of fury. ‘Hurt my hound will you?’ he snarled, ‘There’s for you then, you bitch!’ and he struck her again and again with his cudgel until she moved no more.

When the shepherd found his devastated flock and the broken body of his daughter, his grief was too deep for tears. He did not need to ask who the perpetrator was for the giant’s footprints were all around crushing the sweet meadow grass. He let out a terrible cry that echoed off the sides of Pen Hill and brought the peasants working nearby to his side. The giant, on his way home, heard it too and laughed gleefully.

Hatred of the giant now spread along the valley as never before. It flowed down the banks of the Ure on the tongues of herdsmen and grew hot in secret by a hundred hearth-fires as people remembered his wrongs.

One morning in the autumn of that year, the giant noticed that as the swine trotted past him two by two there was one young boar on its own. A boar was missing.

‘Wolfhead!’ shouted the giant, kicking him viciously. ‘You’re getting old and lazy. You’ve lost a boar! Go and find it, or by Thor I’ll kick your ribs into kindling! Take that as a reminder!’

Wolfhead slunk away into the forest while the giant walked impatiently up and down, counting and recounting his swine. It was noon before he heard Wolfhead’s baying and ran following the sound, to a glade in the wood. There lay the body of one of his most promising young boars, pierced through the heart by an arrow.

The volcano of the giant’s anger poured out. He beat down bushes and trees. He roared so loudly that birds fell out of their nests and people as far away as Hawes stuck their fingers in their ears. Wolfhead, remembering the kicks, crept away on his belly and hid deep in the forest.

When the giant had recovered a little, he flung the dead boar over his shoulder and crashed off home. Seizing the old man, his only servant, by the neck he ordered him to go to the people of Wensleydale and tell them that the Lord of the Dale (he meant himself) commanded that all men who could bear a bow should present themselves at the old meeting-place on the cliff of Pen Hill in a month’s time.

‘Is it for a war?’ wavered the old man, who knew nothing of the death of the boar. ‘Aye, a war of a sort! Tell them that!’ said the giant. ‘And tell them also what will happen to them if they fail to turn up. Be inventive!’

That evening, as the giant sat gloomily by the fire, he realised that something was missing. Wolfhead was not there, thumping his tail and looking fondly up into his master’s face. He went to stand at the door of his keep and scanned the forest below. ‘Wolfhead!’ he roared. ‘Come here this instant!’

There was a slight rustling of the bushes at the edge of the forest. The giant looked closer and saw that Wolfhead was crouching there, cowering. He whistled but the dog did not move. ‘Damn your hide, come here!’ Wolfhead stayed where he was.

The giant’s cudgel was, as usual, in his hand. In a moment of fury, he threw it with all his might, and in a second, the only friend he had ever had was dead.

The month given to the peasants was up. The following day was set for the meeting. The old servant had returned exhausted. He saw that Wolfhead was no longer around, but he did not dare ask questions. He guessed that the hound was dead when the swine no longer appeared two by two in the morning. His master sat by the fire muttering darkly to himself, ‘He asked for it! Disobey me and die!’

The old servant trembled for the fate of the men of Wensleydale.

Perhaps there were some wise peasants who did not obey the giant’s summons, but they were few and far between. The meeting place at the cliff on Pen Hill was filled with men, from old grandsires to half-grown boys. They had all brought their bows as requested and no doubt would have been pleased to use them on the giant if only they had had a brave enough leader, but the fear for their families kept them all cowards.

The giant stood huge and threatening on the brow of the hill. He surveyed the gathering with a sneer. In his hand was an arrow. He held it up.

‘You see this?’ he said. ‘What is it?’ There was a stunned silence. The answer was so obvious that no one knew what to say. They suspected a trap.

‘What is it, you curs?’

One brave man put his hand up. ‘It’s an arrow, Master.’

‘Well done, you old fool! Yes, it’s an arrow. The question is: who does it belong to?’

The peasants looked at one another. If they knew, they were not saying.

‘I ask because I found it – in the heart of

ONE

OF

MY

BOARS

! Give up the bowman or beware my wrath! I’m only going to ask you once!’

A little ripple of movement ran over the assembled men, but still they said nothing.

The giant stared at them for a moment, his face reddening with anger. Who did these slaves think they were? First the girl, then the dog, now this! He was the son of Thor the Thunderer! He would have blood for their disobedience!

‘Very well, if that’s the game you wish to play. You won’t tell me now while your children live, so perhaps you will tell me when they’re dying! Every man must come back here tomorrow bringing with him his youngest child. One child each or I kill all of you! Think about it tonight. Now

GO

!’

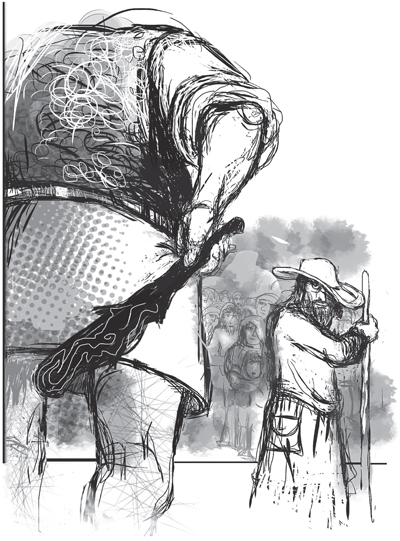

Shaken and sullen, the men turned and retreated down the hill. As they went they passed an old beggar man standing beside the path. He wore a ragged grey cloak and leaned on a staff. His hat was pulled down on one side to hide a missing eye. He nodded at the passing peasants but they were too humiliated to respond or meet his piercing gaze.

‘Who is that man?’ the giant asked his servant.

‘I don’t know his name, my lord. I’ve seen him around from time to time in the Dale, but never spoken to him.’

‘He has an insolent look. Tell him to take himself off!’ As the giant spoke, the old man stirred and moved towards him.

‘What do you want?’ the giant demanded.

‘To get a good look at you,’ replied the old man offensively.

The giant could see no fear in the one flashing eye that gazed sideways up at him. It made him uneasy.

‘Well, now you’ve seen me, so you can take your dirty carcass off.’

‘What do you intend to do to the children?’

‘That’s for me to know and those filth to find out!’

‘It’s Thor’s Day tomorrow.’

‘What do I care? Thor was my father.’

‘He killed warriors and monsters, not children.’

‘How do you know what the great god Thor did, old greybeard?’

‘That’s for me to know and you to find out.’

Suddenly the old man struck the ground with his staff. The blow did not seem hard and yet the rocks rang and the stone keep shuddered. The astonished giant took a step backwards. The old man laughed as he turned away, and the giant and his servant heard him say, almost to himself, ‘Be warned: you stand on the brink!’ He strode swiftly away down the winding path into the Dale but his last words came floating up, ‘One more step and you fall!’

The next morning the giant’s old servant was emptying the slop pail outside the kitchen when he heard a deep croaking. Looking up he saw two huge ravens circling the keep. Round and round they went until the servant was giddy. He was filled with fear, for he thought he knew whose ravens they were; he rushed to tell the giant. His master once more sat by the fire, muttering. The servant recognised the warning signs and he hovered uncertainly.

‘What is it?’ growled the giant. ‘Speak up man, don’t stand there gibbering!’

‘Ravens, Master. Ravens flying around the keep –’

‘Ravens? What do I care for ravens, you idiot?’

‘It’s a warning! Surely you know –’

‘A warning! I’ll give you warning, you idiot!’ and he aimed a vicious kick at the old servant that felled him to the ground. The giant kicked him again and again until he was tired.

‘Are you dead yet?’ he yelled, but there was no reply. The giant spat on the body and, picking up his great cudgel, marched out to await the men of Wensleydale and their children.

But the old servant was not dead. He was badly hurt, but he knew what to do next. He hauled himself to his feet and slowly staggered out to the shed, where the wood and peat for lighting the fire was stored.

‘I’ve seen your ravens, my lord,’ he said to the sky. ‘I know you are with us!’ Then he began to fill baskets with peat. Nine baskets he filled and began, painfully, to drag them into the keep.

The giant had not walked more than a hundred yards from his keep when he noticed something reddish lying across his path. He was filled with an unfamiliar sense of foreboding. As he got closer, he saw nine of his great boars lying dead across the path.

A hundred yards further on there was another nine – and a little further yet, another.

The giant ran now like a wild elephant, so furious that he foamed at the mouth, striking at everything he met with his cudgel. The huge veins in his neck and forehead stood out like hawsers, ‘By Thor! I shall kill every one of them! Smash their heads, beat their bones to flour, pull down their houses, and crush their wives and children! Wensleydale will become a desert!’

The men of Wensleydale stood at the meeting place near the cliff, holding their young children in their arms. The children were afraid and many were crying.

As the sound of the giant’s violent approach reached them they all trembled and some turned to flee, no matter what might happen to them. Suddenly the old man in the grey cloak stood before them. No one had seen him come and yet he was there, not exactly smiling but somehow comforting. Even the most fearful seemed to gain courage from his presence.

As the giant appeared over the crest of the hill, he looked so powerful that no one thought he could be prevented from killing them all. Then the old man stepped forward and held up his staff – or was it now a spear? The giant stopped as dead as if he had run into a wall. Still he waved his cudgel.

‘I know you, Lord of the Gallows!’ he panted. ‘And I defy you!’ The watchers thought that he would strike the old man down but at that very moment two ravens appeared as though from thin air and flew close over his head. ‘Look!’ said the old man, pointing towards the hilltop behind the giant. He swung around and all of them could see a tall plume of black smoke mixed with roaring pillars of flame rising from the direction of the giant’s keep.

‘I did warn you!’ said the old man. He made a small gesture with his hands and the giant’s cudgel splintered and fell to the ground. The giant did not seem to notice, for his eyes were now fixed on something else, something that made them wide with horror. His mighty limbs began to tremble and his mouth fell open. He tried to speak, but could not utter a sound. To the astonishment of all the men of Wensleydale their enemy began to stumble backwards his hands raised as though to protect himself.

Silhouetted against the smoke and fire, two figures were approaching. One was a girl, pale and slender, the other a great boarhound. Their eyes glittered and though they seemed solid enough their feet did not touch the ground. The girl held the boarhound on a leash, but his jaws slavered and his limbs strained as he tried to get at his former master. Back and back the giant staggered until he stood at the very edge of the cliff. Then, nodding briefly to the old man, the shepherd’s daughter loosed the hound. With one spring, Wolfhead leapt at the giant’s throat. Dog and giant went backwards over the cliff together.

D

RAGONS

O

N

D

RAGONS

A fine clutch of eggs, probably laid by dragons from Scandinavian stories brought over by the Vikings, hatched out in North Yorkshire. The hatchlings settled across the county: Sockburn, Handale, Loschy Wood, Slingsby and Sexhow all have tales of dragons and their inevitable destruction by a variety of heroes. Unfortunately, the stories are so similar that one or two are quite enough.

All the dragons appear to have been of a similar type – the sort that coils around a hill, snakelike with poisonous breath, rather than the fire-drakes found further south. (

See

Ragnar Lodbrok and the Founding of York for an early version.) Only one, the Sockburn dragon, could fly. One, the Loschy Hill dragon, whose story is given below, could heal itself by rolling on the ground (a feature borrowed from the Greek legend of Alcyoneus and Heracles). The Sexhow dragon had its skin nailed to the church door whence it was supposedly removed by that man-turned-myth, Oliver Cromwell.

Their diet varied. Some just ate local people, some liked the daily milk of nine cows; one, fussy but a little conventional, preferred virgins.

As for their killers, most go on to marry rich heiresses once they have removed the dragon; however, two heroes and their dogs are tragically killed by their dragon’s poisonous breath, though only after the dragon is safely dead.

One dragon appears to be connected with establishing land tenure. It involved such a weird ceremony that I cannot resist including it briefly here.