Norton, Andre - Novel 08 (21 page)

Read Norton, Andre - Novel 08 Online

Authors: Yankee Privateer (v1.0)

They went rocketing off at a good pace.

"As this pestilent climate would make

anyone feel." Crofts lifted the skirts of his coat and allowed the warmth

to climb his tight breeches. "But at least this is some small improvement

on our last lodging."

Fitz continued to shiver.

"Which

one?

The one in which I met you suits me best.

Aha—food!"

He watched the waiter and an underling bring in heavily laden trays.

"But—are we an army?" He began to be astonished at the number of

dishes they were unloading.

The waiter bobbed his head. "Beggin* your

pardons, gentlemen. But we be so full tonight,

th

'

other officers will dine in 'ere too."

Before Fitz could frame a protest there was a

hearty roar of laughter from the hall, and three men in the red coats of the

army came tramping in upon them, bringing with them the fumes of a strong rum

punch. The well-jowled leader flipped a hand in half-salute to the two by the

hearth and boomed genially:

"Damme, if we ain't being attack in

force, boys

! '

Tis the sea dogs we find in

possession."

Fitz by some miracle regained use of his

tongue.

"Not at all, sir.

We believe that by the

rights of seniority you gentlemen have first call upon the provisions."

Crofts moved up beside him.

"Just

so.

By your permission though, we shall join you in demolishing them.

Lieutenant Crofts of the

Neptune

.”

He bowed and Fitz echoed his movement.

"Lieutenant Lyon, also of the

Neptune

”

"I'm Major Goodwin of the

Forty-fourth," returned the leader of the invading troops. "And this

is Mr. Roberts and Captain Farrier, also of ours."

All three of the military had drunk, even if

they had not dined, but even so Fitz felt a chill crawl down his spine. One

mistaken word or awkward answer could bring disaster on them. He looked to

Crofts for guidance. The Captain was calmly seating himself at the table,

watching the waiter carve their beef with the proper attention of a hungry man.

For a single instant he lifted his eyes to Fitz, and then beyond him to the

door.

Fitz thought of the confusion in the yard

below. There was one precaution which they could still take. He dared to

believe that Crofts meant the next move to be his. He made up his mind.

"If you will excuse me for the nonce,

gentlemen, I find that I have dropped my snuffbox, perhaps in the chaise."

He caught up his hat and cloak.

Crofts was

intent now,

very intent, upon the beef.

"Lord, man, don't venture out in this

muck for it," Captain Farrier was beginning, "let one of the inn

fellows "

Fitz shook his head.

"

Tis

a trinket I put value on," he tried to get meaning into that.

The officer laughed.

"From

a fairest one, eh?

Well, young blood runs

hot "

Fitz ducked out of the door and fairly ran

down the

passage

and out into

the yard, pausing for a moment to locate the stables. A dark figure slid out

from an archway.

"What's to do, sir?" In that soft

whisper Fitz recognized their postilion. He remembered the recommendation of

their

Plymouth

benefactor.

"There may be trouble. Could you have two

horses waiting?"

The man betrayed no surprise. "Two horses

it is, sir.

As soon as I can make it.

And over by that

window they'll be—that looks into the Bow, sir. Take

this

"

Fitz's fingers closed about the chill metal of

a pistol. The postilion faded away again.

So that window looked into the Bow, did it? He

began to edge along the wall toward the square of light.

Here's to the squire who goes to parade,

Here's to the citizen soldier;

Here's to the merchant who fights

for his trade,

Whom danger

increasingly makes bolder.

—THE VOLUNTEER BOYS

With his fingernails, Fitz dug at the casement

until he was able to edge it open toward him. The candle-lighted table was the

center of activity within. And Crofts, with an empty place at his right, was

facing the window. The Captain was giving full attention to his plate, but,

just as the casement swung open far enough for Fitz to hear what was being

said, the Major asked loudly:

"

Neptune

, eh?

Then you'll be shipmates with Johnny

Cross "

Crofts chewed ostentatiously. But there was a

note in the Major's voice which made the Marylander very glad he had taken his

precautions. Crofts came to the last swallow of a mouthful he could mince no

finer.

"Cross—Cross," he repeated with a

slight frown. "Cross?"

The Major put plump hands on the table edge

and worked himself forward on his chair.

" 'Tis

odd that

you are not more knowing of your Captain's name, Lieutenant."

Crofts laid down his fork and Fitz jerked open

the window to its fullest extent. The curtain caught the breeze and billowed

out into the room. One of the officers cried out, pointing to the fluttering

strip of muslin. But Crofts gained his feet in one supple motion as Fitz

reached in his arm to pull the curtain away. Then he took a chance at the

greatest shot of his life, aiming with the postilion's pistol at the shaft of

the candelabra which lit the room.

The explosion of the shot was echoed by shouts

as the flaming candles snuffed out on the cloth. Fitz jumped back as the window

square framed a squirming shadow. But he was able to give the last tug which

brought Crofts through safely.

"This way, sir!"

The postilion called from behind the coach. He was holding the reins of two

horses. "And for God's sake, sir, keep t' th' road, if ye can. Th' moor be

a death trap fer 'em as knows it not!"

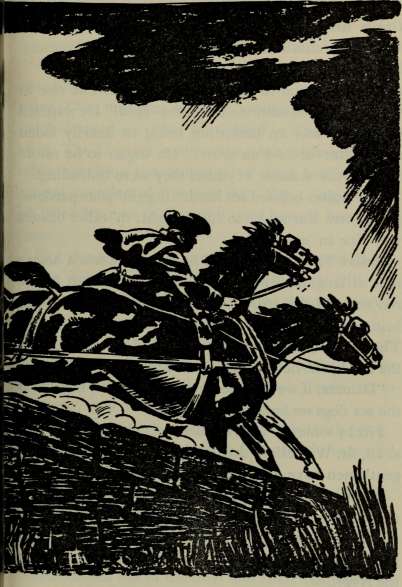

Crofts scrambled awkwardly onto his chosen

mount, and Fitz swung onto his, jamming the pistol into the empty holster on

the saddle. Behind them the shouting was louder and a circle of lanterns burst

out of the inn door.

"Come on!" Fitz dug his spurless

heels into his mount and headed through the courtyard arch onto the post road.

Crofts pounded just behind him.

The fog seemed to deaden all sound so that

they rode in a kind of muffled, feather-shrouded world—rode hard, holding to

the road as their only guide. It wasn't until that road split into two that

Fitz reined up and looked back for the Captain. But Crofts was not there.

Nowhere in the dense curtain of fog did there appear to be another moving

creature.

Fitz shivered with a chill which was not born

of the dank mist about him. He was alone—on a moor road! Some of the accidents

which might have overtaken Crofts ran through his mind. There was the chance of

straying from the track into one of the death-bogs, a bad fall into a ditch,

recapture . . .

He pulled rein and turned back along the way

he had come. And a pace or two away from the crossroad he was rewarded by a

glimpse of a dark shape fading into the mist. Fitz began to whistle—that shrill

pipe which had marked the time for Ninnes' recruiting song so long ago in

Baltimore

. Since a shout might betray them to the

hunters, that tune might identify him to his companion. He followed the shape

into the dark and—off the post road.

Twice more he caught sight of the flying

shadow, but even when he ventured to call there was no slackening of pace. Then

he believed that he had heard a cry for help from some distance ahead. He sent

his mount plunging on.

Straight out of the murk

loomed a black prickly wall of hedge.

There was no time to search for a

break. And with the eye of a horseman used to riding over rough land, he gauged

it not too high. He might not be mounted on a hunter from the Fairleigh

stables, but he guessed that the postilion had given them the best possible

horses available. So he booted the brute into a jump.

There was a single sickening moment of

awareness of his folly as together they plunged over and down —down into a gulf

which had no end. Then Fitz struck bottom with a blow which flattened the air

out of his lungs. He lay still in utter blackness.

Gravel dug painfully into his face and his head

was one blinding pain. He dragged himself up to his elbows and rested before he

could pull himself to his knees. Then he was instantly and thoroughly sick,

with a retching which left him empty and weak. But his will would not let him

rest. He clawed about in the dark until his fingers closed on a spiky bush

which gave him some support to gain his unsteady feet.

He fell again twice before he had moved six

feet, and only a semiconscious will kept him going.

All the

world was a black pocket through which he had to pull himself with his two

palm-raw T hands.

The last time he fell it was onto a patch of

waterlogged stuff which gave some ease to his scraped face and hands. He

allowed himself some precious rest there before he got doggedly to his feet again.

His head was throbbing with a regular

rhythm—it was almost like the tolling of a bell, sonorous and deep. He held his

head in his torn hands for a long moment before he realized dimly that there

was a bell sounding somewhere, ringing with steady chime. Instinctively he

started on toward the source of that tolling.

Once he came up against a great block of what

was rough stone under his questing fingers. And he clung there for some time,

panting and listening to the bell. But at last he forced his tired body on.

He reached the wall which lay beyond, and

tumbled over its low barrier. The bell was very close now—its clamor adding to

the pain behind his half-closed eyes. Yet he must get up and find it—that was

somehow important.

There were tall gray stones standing upright

in the space behind the wall, stones he stumbled against before he sighted them

or could fend himself away from their hardness. But at last he reeled into the

place of the bell and fell, for the last time, into a yellow circle of lantern

light.

"Godfrey! Godfrey!" Fitz could

barely hear the voice or feel the hands tugging at him. "Godfrey-come here

at once, man!"

Fitz gave up fighting and slipped down into

the darkness, leaving even pain behind him.

He awoke—to be faced with the round furry

countenance of a cat watching him with unblinking yellow eyes. The face split

in a wide yawn, a pink, pointed tongue curled up. Then

came

a soft, comfortable rumble of sound which was somewhat soothing to the faint

ache behind his eyes. His hands explored the surface on which he lay. He was in

a bed true enough, a soft, well-made bed, and there was a hot wrapped brick

between his two feet.

The cat, curled in comfort at the foot of the

bed, again opened its sleepy eyes and looked beyond Fitz at someone outside the

range of his vision. Fitz was too lazy to turn his head to see the disturber of

the peace they shared.

"Noll!" the whisper was an

exasperated one. "So this is where you disappeared to, you son of dark

powers!"

Noll yawned for the second time and paid

delicate attention with the tip of a pink tongue to the toes of his right front

paw. He did not deign to notice the whisper. A small man in a spruce black coat

and freshly laundered lawn bands came to the foot of the bed and was about to

pick up the cat when he noticed Fitz's eyes fixed dreamily upon him. He

straightway forgot his errand and came to the head of the bed, a smile of real

pleasure creasing the tight wrinkles of his gentle face.

"So, my boy, you are awake ..."

"Yes, sir . . ." Fitz found it

something of an effort to pull those words out to use. It was so much easier to

lie there drowsily and let

himself

slip off again into

the warm darkness.

The little man's dry hand touched his

forehead, and then slipped lightly down to rest on the pulse which beat in his

throat. He nodded twice as if pleased and was gone, almost before Fitz noticed

his going. Fitz blinked at Noll and closed his eyes. Noll had the proper

idea—now was the time for sleep.

But when he aroused for the second time there

was no thin shaft of sunlight across his bed. Instead candlelight made bright

the pattern of the cover under which he lay. And now he pulled himself up a

little and looked around with real curiosity.

The room was a comfortable one, although small

and with old-fashioned furnishings. And from somewhere a delightful odor was

seeping in. He recognized the emptiness of hunger and was impatient for food.

Then out of nowhere Noll came, a black and white shadow, to leap up on the bed

and prowl the length of Fitz's body, seating himself with his tail curled over

his paws to watch the American with cold interest.

But a moment later Noll's master came in with

a second candle, followed by a large young man in the leather breeches of a

groom who carefully carried before him a tray bearing a covered bowl. Noll so

far forgot himself as to greet them with a soft meow.

"Get down!" the little man made

brushing motions.

"Away with you, sir.

Your

supper is on your plate.

Just where it always is.

Begone and get it!"

Noll moved down the bed, leaped from the foot

and disappeared. The young man put down the tray and stepped to the bed.

Without saying a word he deftly raised Fitz against the pillows and so widened

the boundaries of the American's world. The host nodded.

"Well done, Godfrey. I shall ring when

you are needed. And now, my boy, I think perhaps a bit of soup?"

He whisked the cover off the bowl, and with a

silver spoon set about feeding Fitz some capital chicken broth with a dexterity

which Fitz admired. When the scraping of silver against china announced the end

of the course, the little man brought from by the fire a small pan, the

contents of which he poured into a cup and held to Fitz's lips.

"Down this, my boy, you'll be the better

for it tomorrow. You have had a most merciful escape from lung fever—a most

merciful escape!"