Nostrum (The Scourge, Book 2) (31 page)

Read Nostrum (The Scourge, Book 2) Online

Authors: Roberto Calas

“There,” he says. “In two days you will be cured.”

I thank him as he cleans up the clutter of his tools, but I can’t help wondering what the House of Gemini has to say about his cure.

Tristan pulls a ceramic phial from a rack on the workbench. He takes a phial from his belt and compares them. The two look identical.

“Where did you get that?” The alchemist straightens the rack of phials so that they are perfectly flush with the edge of the bench again.

“From you, apparently,” Tristan replies.

“Give it to me,” the alchemist says. “That is dangerous. You should not have it.”

“Dangerous?” Tristan puts his phial away and unstoppers the other. “I bet it’s a cure for the plague.” He lifts it toward his mouth. The alchemist crosses his arms and watches. “You aren’t going to stop me?” Tristan asks.

“I warned you already,” he replies. “The world is better off without fools who drink things they have been warned not to. Besides, I am running out of murderers and rapists. I could use another test subject.”

“You are a pitiless bastard.” Tristan stoppers the phial.

“Pity is a luxury,” he responds. “And, at times of calamity, luxury is the first thing to die.”

“Murderers and rapists?” Belisencia asks.

“Yes. Lord Warwick gave me thirty prisoners from his dungeons to help test my work.” He nods to the phials. “Those contain the blood of plaguers. It is how I afflict the prisoners.”

The mystery is solved. The simpleton gave Isabella the Witch phials of plaguer blood. I say a prayer for the afflicted souls of Danbury. Souls that we afflicted with our good intentions. A thought comes to me.

“You have a cure,” I say. “That’s why you didn’t stop Tristan when he pretended to drink from the phial. You have a cure.”

The alchemist looks at me curiously. “A peculiar conclusion. How did you reach it?”

I glance at Tristan, then look back to the alchemist and shrug. “Reason?”

“A warrior playing with reason is like a child playing with a loaded crossbow.”

“So there is no cure?” Fear stabs at me.

“I didn’t say that.”

My chest rises and falls with each breath. I force myself to unclench my fists. “Stop playing games, man!” I say. “Is there a cure?”

The alchemist glances toward his guards, then at the men strapped to the tables. He looks back at me and sighs. “There is—”

A multitude of distant shouts rise up from outside. Even from the top of this tower I can hear the hatred in the voices. The violence.

The alchemist rushes to the arched window and looks out. He appears calm, but his fingers turn white on the sandstone ledge.

“They’re back.” He says it quietly, then turns toward the blond guard. “There are too many this time, Daniel.” He looks at us with drooping eyes. “I am so very sorry. You will die with us now.”

I push past the alchemist and gaze out from the tower window. A priest is the first thing I see, and it makes me sigh. Men have become savage as dogs in these dark times, and priests are the huntsmen who set those dogs loose upon the world.

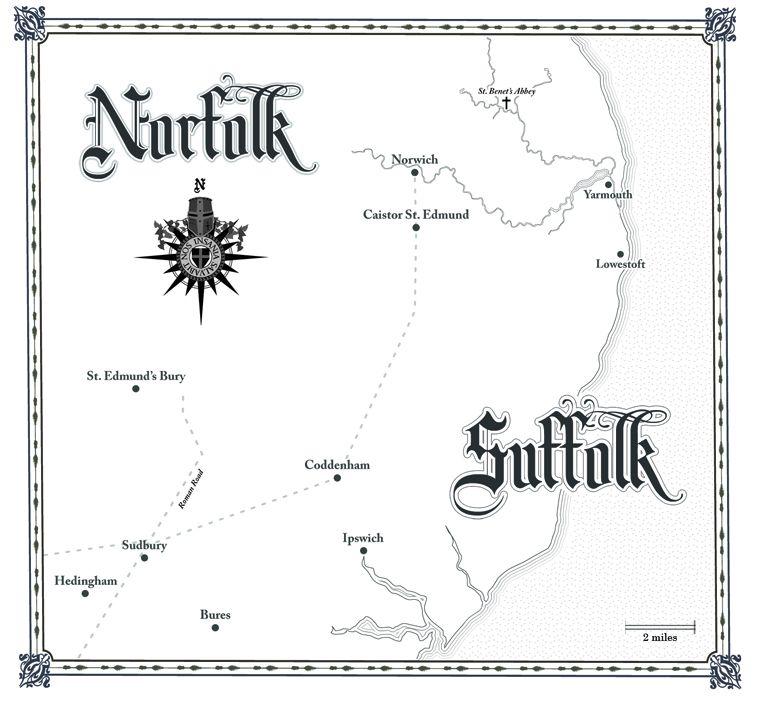

The priest is a longbow shot away, on the opposite side of the River Bure, but I can see his robes clearly. Two younger clergymen trudge at his side, their heads cowled and bent forward. Behind these three men march scores of peasants wearing wool, linen, and scowls. Some of the men drag small rowboats along the marsh. It is the peasants who shout. I cannot make out their words, but the sharp, angry cries and the weapons in their hands deliver the message clearly: they are hounds, and the hunt is afoot.

“Between ninety and a hundred of them,” I say. “And six boats. Looks like they’re out for blood. Are you the fox?”

The alchemist collapses onto a stool beside the workbench and shakes his head. “There are only seven guards here at the abbey,” he says. “Remember when I asked if you could bring soldiers?”

Tristan looks through the window. “It’s just priests and farmers,” he says. “What do you need soldiers for?”

“This is a monastery, not a castle,” the alchemist replies. “They have spent weeks searching for a way in. And they have found it. They know the docks are our weakest point, and today they have brought boats to get them there.”

“What do they want?” Belisencia asks.

The alchemist picks a thread from his robe. “They want to apply flame to my body. Alchemy, apparently, is a sin.”

“So is murder,” Tristan replies.

“There’s still time,” I say. “They haven’t reached the Bure yet. You were about to tell us if there is a cure.”

“What does it matter?” the alchemist replies. “It’s not the plague that will kill us today. There is no cure for fire or steel.”

“We will rid you of those peasants,” I say. “Tell us about the cure.”

The alchemist looks toward the window as the shouts grow ever louder. “You cannot defeat a hundred men.”

“We will,” I say.

“We will?” Tristan asks.

The shouts are dangerously close now. Other voices rise against them. Probably the halberdiers from the abbey warning then off. The alchemist gazes toward the window and straightens a cross that hangs from his neck. He looks back at me. “How can you possibly fight them all?”

“You said it yourself,” I reply. “I am a fighting man.”

A unified cry rises from the mob. The huntsmen are working the dogs into a blood frenzy.

“Is there a cure?” My heart batters my chest. If I knew there was a cure, I could fight ten thousand peasants and whistle as I did. “

Is there a cure

?”

The alchemist glances toward the window again, runs his hands through his hair, then nods. “Yes,” he says. “There is a cure.”

It is as if every voice in heaven erupts into song. As if the skies rain gold and silver. It is as if all of God’s angels explode in my heart and shower my soul with the blood of Christ. I am not certain that is a good thing, but if it is, that is what I feel. I am drunk with exultation.

Hallelujah!

It is the most spiritual moment I have experienced. I feel the touch of God, and it is an alchemist’s sin that is responsible.

There is a cure!

A beam from the setting sun splashes through the arched window like God’s smile. Tears flood my eyes. I fall to my knees and cover my face with my hands. There can be no words more beautiful, more powerful, more heavenly.

There is a cure!

I will start a new religion, and its bible will hold only four words.

There is a cure!

I will climb the mountains of Asia and shout madly from their peaks.

There is a cure!

I will dance with the King of France, laugh wildly, and sing the words.

Existe un remède!

And Elizabeth will be at my side through it all. My Elizabeth. I will see her crooked half smile again. I will kiss those long, pale fingers. I will trace figure eights around the freckles of her legs and bury my nose in her flaxen hair.

There is a cure!

The alchemist clears his throat. “There is a cure,” he says. “But I do not have any left. And I cannot make any more.”

I dream that I am under a red ocean. Perhaps it is the hairy sea. And in that dream I am killing a man.

My hands hold his neck. My fingers squeeze, but as in all dreams, something stops me from achieving my goal. Something keeps my fingers from closing around the man’s throat.

Tristan is in that dream. And so is Belisencia. Their faces are wild. Their mouths move as if they are screaming, but I cannot hear them. Probably because I am under the red waves of the hairy sea.

Some unseen force latches onto me from behind. Perhaps it is a hairy tick. More of them latch onto me and pull. The red water slowly turns clear.

A murky droning sound drifts to my ears. An urgent song of the sea that becomes more and more persistent. It sounds like Tristan.

“Let him go!” Tristan shouts. He holds one of my hands.

“You’ll kill him!” Belisencia shrieks. She holds my other hand.

A guard behind me has his arms around my waist. Another has his hand on my face and is pulling my head backward. The man I am killing is the alchemist, of course.

I should not be killing the alchemist, so I release him.

The guards wrestle me to the ground, shouting for me to cease. One of the guards clouts me on the back of the head. Tristan kneels and shelters me from the guards.

“It’s all right, Ed,” he says. “It’ll be all right.”

“He is desperate,” Belisencia pleads with the alchemist. “His wife is plagued.”

The alchemist looks at me and something in his expression softens. All of the shouts from outside have quieted except for one. A single voice screaming in the singsong of prayer.

I look up at the alchemist, my breath coming in gasps. He has fallen back against the workbench and instead of looking at me, he studies the mess behind him. He holds one hand to his throat and with the other he absently picks up toppled jars and phials. He does not look at me until all the objects are righted.

“What…what do you mean?” I say. “If you have the cure, you must make more.”

The alchemist straightens himself and tugs at his tunic. “I cannot make more. It is impossible.”

The guards loosen their hold on me. I push myself upward with one hand, and my arm trembles under my weight.

“Why?” I ask. “Why is it impossible? I don’t understand.”

The alchemist returns his attention to the workbench, his hands shifting each of the objects by the barest of degrees. His eyes are calculating, comparing, judging their positions. But his hands shake, and a flush stains his cheeks. “Because sometimes there are no bridges across rivers,” he says. “Sometimes you have no boats and the currents are too strong. I cannot make more of the cure.”

“You are the only one capable of saving this kingdom,” I say. “You must make more! It is injustice to sit by idly while the kingdom dies!”

The alchemist whirls around, his elbow brushing a round-bottomed flask and knocking it off the bench. The glass shatters with a crisp finality.

“What do you know about injustice?” His eyes are slits beneath his brows. “I haven’t left this monastery in nearly three months, and I have spent most of that time here, in this tower. I work all day every day long into the night, sleeping only after the sun has risen again. But not even sleep allows me escape from my labors, because my dreams are of waters and waxes and tinctures and inductions. But I continue. I continue despite the priests and villagers at my gate. They call me a demon and a miscreant and Satan’s dog. I suffer dead animals hurled over the walls. I have been burned in effigy a dozen times. The very people I am trying to save want to murder me. But I continue. Always I continue. And do you know what the true injustice is?”

“That we are subjected to your boring rant?” Tristan asks.

“That I cannot make a cure!” The alchemist closes his eyes and the rage melts away. His shoulders shake and tears squeeze past the clench of his lids. “I have failed. And I continue to fail. All of the suffering has been for naught. I am incapable of making a cure.

That

is the true injustice.” He collapses back into the stool.

I swallow a flood of bile and will myself not to vomit. “But you said…” I cannot speak.

“You told us there was a cure,” Belisencia says gently.

The alchemist nods without opening his eyes. “There is a cure,” he replies. “But it is not mine. That is the second great injustice of my existence.”

Tristan helps me rise to my feet. “Whose cure is it?” I ask, my voice shaking.

The alchemist opens his eyes and looks skyward. “It belongs to an old man,” he says. “A traveling peddler named Gregory the Wanderer.”

I am glad Tristan is holding my arm because I think the alchemist’s words would have toppled me otherwise. Gregory the Wanderer. The peddler who traded us the phials of plague, calling them a cure. We gave one of those phials to the villagers of Danbury and afflicted the lot of them. Why would Gregory have traded with Isabella the Witch for phials he thought contained a cure if he already had a cure? Phials that he obtained from this very alchemist.

Someone pounds on the tower door and tells us what we already know. “A mob approaches! And they have boats!” It sounds like John, the drunk from the gatehouse.

“I answered your question,” the alchemist says. “I believe you have a hundred peasants to drive off.” His tone implies that he has little faith that we will be true to our word. The pounding on the door grows more violent.

“Daniel! Wilfred! We need you at the docks!” shouts John.

“I have more questions,” I say.

“Shall I answer them on the pyre?”

“We are not finished with this conversation,” I say.

The peasants cheer loudly outside. The priest is no doubt giving them a rousing speech. I stride to the window and look out. The crowd is assembled at the far riverbank, the boats poised on the shore. In a few moments, the Bure will be swarming with angry men. If they reach the docks, there are only wooden doors to stop them. I have seen what happens when frustrated armies finally breach a city wall. It is a hell that makes the scenes in Matheus’s tapestry look like children at play. I have never been on the wrong side of that hell, and I do not wish to be today.