Notebooks (12 page)

Authors: Leonardo da Vinci,Irma Anne Richter,Thereza Wells

Tags: #History, #Fiction, #General, #European, #Art, #Renaissance, #Leonardo;, #Leonardo, #da Vinci;, #1452-1519, #Individual artists, #Art Monographs, #Drawing By Individual Artists, #Notebooks; sketchbooks; etc, #Individual Artist, #History - Renaissance, #Renaissance art, #Individual Painters - Renaissance, #Drawing & drawings, #Drawing, #Techniques - Drawing, #Individual Artists - General, #Individual artists; art monographs, #Art & Art Instruction, #Techniques

How the river Po in a short time might dry up the Adriatic Sea in the same way as it has dried up a large part of Lombardy.

46

3. WATER AND AIR46

Write how the clouds are formed and how they dissolve, and what it is that causes vapour to rise from the water of the earth into the air, and the causes of mists and of the air becoming thickened, and why it appears more blue or less blue at one time than at another; and describe also the regions of the air, and the cause of snow and hail, and how water contracts and becomes hard in ice, and write of the new shapes that snow forms in the air, and of the new shapes of leaves on the trees in cold countries, and of the pinnacles of ice and hoar-frost making strange shapes of herbs with various leaves, the hoar-frost making as if it might serve as dew ready to nourish and sustain the said leaves.

47

47

The movement of water within water proceeds like that of air within air.

48

48

Acoustics

Although the voices which penetrate the air proceed from their sources in circular motion, nevertheless the circles which are propelled from their different centres meet without any hindrance and penetrate and pass across one another keeping to the centre from which they spring.

Since in all cases of movement water has great conformity with air, I will cite it as an example of the above-mentioned proposition. I say: if at the same time you throw two small stones on a sheet of motionless water at some distance from one another, you will observe that round the two spots where they have struck, two distinct sets of circles are formed, which will meet as they increase in size and then penetrate and intersect one another, while always keeping as their centres the spots which were struck by the stones. And the reason of this is that although apparently there is some show of movement there, the water does not leave its places because the openings made there by the stones are instantly closed again, and the motion occasioned by the sudden opening and closing of the water causes a certain shaking which one would describe as a tremor rather than a movement. And that what I say may be more evident to you, watch the pieces of straw which on account of their lightness are floating on the water and are not moved from their original position by the wave that rolls beneath them as the circles reach them. The impression on the water therefore, being (in the nature of) a tremor rather than a movement, the circles cannot break one another as they meet, and as the water is of the same quality all through its parts, transmit the tremor from one to another without changing their place. For as the water remains in its position it can easily take this tremor from the adjacent parts and pass it on to other adjacent parts, its force steadily decreasing until the end.

49

49

Just as the stone thrown into the water becomes the centre and cause of various circles, and the sound made in the air spreads out in circles, so every body placed within the luminous air spreads itself out in circles and fills the surrounding parts with an infinite number of images of itself, and appears all in all and all in each part.

50

50

Air

Its onset is much more rapid than that of water, for the occasions are many when its wave flees from the place of its creation without the water changing its position; in the likeness of the waves which the course of the wind makes in cornfields in May, when one sees the waves running over the fields without the ears of corn changing their place.

51

51

The elements are changed one into another, and when the air is changed into water by the contact it has with its cold region this then attracts to itself with fury all the surrounding air which moves furiously to fill up the place vacated by the air that has escaped; and so one mass moves in succession behind another, until they have in part equalized the space from which the air has been separated, and this is the wind. But if the water is changed to air, then the air which first occupied the space into which the aforesaid increase flows must needs yield place in speed and impetus to the air which has been produced, and this is the wind.

The cloud or vapour that is in the wind is produced by heat and it is smitten and banished by the cold, which drives it before it, and where it has been ousted the warmth is left cold. And because the cloud which is driven cannot rise because the cold presses it down and cannot descend because the heat raises it, it therefore must proceed across; and I consider that it has no movement of itself, for as the said powers are equal they confine the substance that is between them equally, and should it chance to escape the fugitive is dispersed and scattered in every direction just as with a sponge filled with water which is squeezed so that the water escapes out of the centre of the sponge in every direction. So therefore does the northern wind become the origin of all the winds at one and the same time.

52

52

That wind will be of briefer movement which is of more impetuous beginning; and this the fire has taught us as it bursts forth from the mortars, showing us the form and speed by the smoke which penetrates the air in brief and scattered motion. But fitful impetuosity of the wind is shown by the dust that it raises in the air in its various twists and turns. One perceives also between the chains of the Alps how the clashing together of the winds is caused by the impetus of various forces; one sees how the flags of ships flutter in different currents; how on the sea one part of the water is struck and not another; and the same thing happens in the piazzas and on the sandbanks of rivers, where dust is swept away furiously in one part and not in another. And since these effects show us the nature of their causes we can say with certainty that the wind which has the more impetuous origin will have the briefer movement; and this is borne out by the aforesaid experiment showing the brief movement of the smoke from the mouth of the mortar. And this arises from the resistance that the air makes on being compressed by the percussion of this smoke which in itself also suffers compression in offering resistance to the wind. But if the wind is of slow movement it will extend over a very long way in a straight course, because the air penetrated by it will not become condensed in front of it and will not thwart its movement, but will readily expand spreading its course over a very long space.

53

4. EARTH, WATER, AIR, AND FIRE53

Leonardo is here making the ascent of the Monte Rosa on a fine summer’s day with an intensely blue sky overhead. His desire is to peer into those upper regions which are beyond the atmosphere—the sphere of the Element of Fire. His surmise that they are regions of ‘immense darkness’ and that the blue colour of the sky is due to the reflection of light by small particles in the air is correct.

Of the colour of the atmosphere

I say that the blue which is seen in the atmosphere is not its own colour but is caused by warm humidity evaporated in minute and imperceptible atoms on which the solar rays fall rendering them luminous against the immense darkness of the region of fire that forms a covering above them. And this may be seen, as I myself saw it, by anyone who ascends the Monte Rosa, a peak of the Alps that divides France from Italy. . . .

There I saw the dark atmosphere overhead and the sun as it shone on the mountain was far brighter here than on the plains below because a smaller extent of atmosphere lay between the summit of the mountain and the sun. [

See p. 310

.]

See p. 310

.]

As a further illustration of the colour of the atmosphere, we may take the smoke of old and dry wood, which as it comes out of the chimneys seems to be a pronounced blue when seen against a dark space. But as it rises higher and is seen against the luminous atmosphere it turns immediately to an ashen grey hue. And this happens because it no longer has darkness beyond it. . . . If the smoke comes from young green wood it will not assume a blue colour, because as it is not transparent and is heavily charged with moisture it will produce the effect of a dense cloud which takes distinct lights and shadows as though it were a solid body. The same occurs with atmosphere which excessive moisture renders white, while little moisture acted upon by heat renders it dark, of a dark blue colour. . . . If this transparent blue were the natural colour of the atmosphere it would follow that wherever a greater quantity of the atmosphere intervened between the eye and the element of fire the shade of blue would be deeper; as we see in blue glass and in sapphires, which are darker in proportion as they are thicker. But the atmosphere in such circumstances acts in exactly the opposite way, since where a greater quantity of it comes between the eye and the sphere of fire, there it appears much whiter. This happens towards the horizon. And the less the extent of atmosphere between the eye and the sphere of fire of so much the deeper blue does it appear, even when we are in the low plains. It follows therefore, as I say, that the atmosphere assumes this azure hue by reason of the particles of moisture which catch the luminous rays of the sun.

54

54

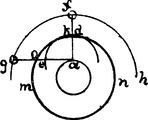

Prove that the surface of (the sphere of) the air where it borders on the fire, and the surface of the (sphere of) fire where it ends are penetrated by the solar rays which transmit the images of the heavenly bodies, large when they rise and small when they are on the meridian.

Let

a

be the earth and

ndm

the surface of the air bordering on the sphere of fire;

hfg

is the orbit of the sun; then I say that when the sun appears on the horizon

g

its rays are seen passing through the surface of the air at a slanting angle—

om

; this is not the case at

dk

. And so it passes through a greater mass of air.

55

a

be the earth and

ndm

the surface of the air bordering on the sphere of fire;

hfg

is the orbit of the sun; then I say that when the sun appears on the horizon

g

its rays are seen passing through the surface of the air at a slanting angle—

om

; this is not the case at

dk

. And so it passes through a greater mass of air.

55

Of the heat that is in the world

Where there is life there is heat, and where vital heat is, there is movement of vapour. This is proved inasmuch as we see that the element of fire by its heat always draws to itself damp vapours and thick mists as opaque clouds which it raises from seas as well as lakes and rivers and damp valleys; and these being drawn by degrees as far as the cold region, the first portion stops, because heat and moisture cannot exist with cold and dryness; and where the first portion stops, the rest settle, and thus one portion after another being added, thick and dark clouds are formed.

They are often wafted about and borne by the winds from one region to another, where by their density they become so heavy that they fall in thick rain; and if the heat of the sun is added to the power of the element of fire, the clouds are drawn up higher still and find a greater degree of cold, in which they form ice and fall in storms of hail. Now the same heat which holds up so great a weight of water as is seen to rain from the clouds, draws them from below upwards, from the foot of the mountains, and leads and holds them within the summits of the mountains, and these finding some fissures, issue continuously and cause rivers.

56

56

As water flows in different ways out of a squeezed sponge, or air from a pair of bellows, so it is with the thin transparent clouds that are driven up on high through the reflection occasioned by the heat; the part which finds itself uppermost is that which first reaches the cold region and there halted by the cold and dryness awaits its companion. The part below ascending towards the part that is stationary treats the air that is in between as though it were a syringe, and this then escapes crosswise and downwards; it cannot go upwards because it finds the cloud so thick that it cannot penetrate it.

And for this reason all the winds that make war upon the earth’s surface descend from above, and when they strike upon the resisting earth they produce a movement of recoil, which as it tries to rise meets the descending wind, and thereby the ascent is constrained to break its natural order, and taking a transverse route pursues a violent course which grazes incessantly the surface of the earth.

And when the aforesaid winds strike upon the salt waters, then their direction becomes clearly visible, in the angle that is formed by the lines of incidence and of recoil; and from these result the proud and menacing and engulfing waves, of which one is the cause of the other.

As the natural warmth spread through the human limbs is driven back by the surrounding cold which is its opposite and enemy flowing back to the lake of the heart and the liver fortifies itself there, making of these its fortress and defence, so the clouds being made up of warmth and moisture, and in summer of certain dry vapours, and finding themselves in the cold and dry region, act after the manner of certain flowers and leaves which when attacked by the cold hoar-frost pressing cold together offer a greater resistance.

Other books

Descent by David Guterson

Contact Imminent by Kristine Smith

Getting Rough by Parker, C.L.

Straight from the Hart by Bruce Hart

The Dance of the Seagull by Andrea Camilleri

For the Memory of Dragons by Julie Wetzel

The Origin by Youkey, Wilette

Balance (Off Balance Book 1) by Lucia Franco

Born of Magic: Gargoyle Masters, Book 2 by Missy Jane

La química secreta de los encuentros by Marc Levy