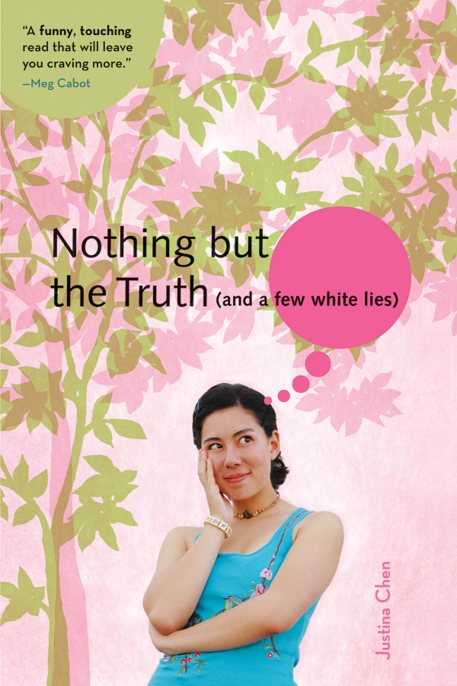

Nothing But the Truth

Read Nothing But the Truth Online

Authors: Justina Chen

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction / People & Places - United States - Asian American, #Juvenile Fiction / Social Issues / General

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

For Tyler and Sofia,

my hapa kids who are wholly wonderful

Belly-Button Grandmother

Belly-Button GrandmotherW

hile every other freshman

is at the Spring Fling tonight, I have a date with an old lady whose thumb is feeling up my belly button.

I turn my head to the side and catch a whiff of mothballs and five-spice powder on Belly-button Grandmother’s stained silk tunic and baggy black pants. At this moment, Janie and Laura are dancing in the gym that’s been transformed into a tropical paradise for the last all-school dance of the year. Me, I’m stretched out on this plastic-covered sofa with my T-shirt pushed up to my nonexistent chest and my pants pulled down to my boy-straight hips.

“You gonna get in big accident,” announces Belly-button Grandmother in her accented English, still choppy after living in Seattle for over fifty years. She smacks her lips tight together, which wrinkles her face even more, so that she looks like a preserved plum. The fortune-teller closes her eyes and her thumb presses deeper into my belly button.

“When you fifteen,” she says. A bead of sweat forms on her forehead like she can feel my future pain.

I muffle a snort,

Yeah, right.

Considering my life is nothing but school, homework, and Mama, broken with intermittent insult-slinging with my brother, there’s hardly any opportunity for me to get in a Big Accident.

“Aiya!”

mutters Belly-button Grandmother, on the verge of another dire prediction.

If my mom wanted my future read, why couldn’t she have found a tarot reader? I’m sure somewhere in the state of Washington there’s a Mandarin-speaking, future-reading tarot lady. Or a palmist who’d gently run her finger across my hand. Someone who would say,

My goodness, what a long happy life you’re going to have.

But no, my future is being channeled through my belly button.

As soon as Mama heard from The Gossip Lady in our potluck group about Belly-button Grandmother, she packed me up and hauled us both down the freeway. This is my mom, the woman who drives only in a five-mile radius around our home, a whole hour south of Seattle. The woman who has driven on a highway maybe twenty times

ever.

The same woman who looks at maps the way I look at her Chinese newspapers: unreadable.

Belly-button Grandmother’s bone-dry thumb presses harder into my stomach like she wants to dig right through me. If she presses harder, I won’t have a future. I wince. She scowls. I would say something profound like,

Hey, that hurts!

if I wasn’t afraid that the old lady was going to change my future.

Belly-button Grandmother sighs like my life is going to be filled with even more disaster than it is now with this Mount Fuji–sized pimple on my chin.

“You gonna have three children. Too many,” she pronounces. For a brief moment, she releases the pressure on my belly and stares down at me with her cavern-dark eyes. “You want me take away one?”

I want to say,

Get real.

How can I even think about conceiving three kids, much less discuss family planning, when I can’t even get a date to my school dance?

Belly-button Grandmother’s frown deepens as if she read my insignificant thoughts. Her thumb hovers over my stomach. Quickly, I shake my head. I don’t need my mom to translate the look on the fortune-teller’s face:

Oh, you making a big mistake.

Now I turn my face to the side so I don’t have to look at Belly-button Grandmother and her disapproval anymore. Above the couch, white paint is peeling off the wall next to the picture of Buddha, his smooth, flat face serene. I wonder what other predictions he’s heard Belly-button Grandmother make and whether he’s having himself a good belly laugh about how the closest I’ve ever gotten to Nirvana is winning a sixth-grade essay contest about why I loved being an American. My field trip to Nirvana was a short one. Steve Kosanko didn’t see me as anywhere close to being a true red-white-and-blue American. The day after I won the contest, he cornered me at recess and serenaded me with a round of “Chinese, Japanese, dirty knees, look at these.” As an encore, he held me down in the mud like it was some squelchy rice paddy where my dirty knees belonged.

Another sniff, this time of incense, makes me want to gag. I need to sneeze, but rub my nose hard instead. A sneeze would probably contract my abs, and then, God, my whole life course could be altered.

What I really want to know, desperately need to know, is whether Mark Scranton, Mr. Hip and Cool at Lincoln High, will ever notice me. Well, technically, he does notice me. I did write his campaign speech, after all. But it’s too much to hope that I’ll actually get a chance to date him, not with Mama’s no-dating-until-college edict (strike one), Mark being a white guy (strike two) and me being a bizarrely tall Freakinstein cobbled together from Asian and white DNA (strike three). I’m out before I’ve even scooted off the bench.

So a more realistic miracle that I’ll take to go, please, is an Honors English essay, one that needs to be started and finished this weekend. The same essay that the rest of the class has worked on for nearly the entire year.

I don’t need a miracle, tarot reader, palmist, or even a Belly-button Grandmother to tell me what my mom is doing out in the waiting room. She’s praying to Buddha: “Please let my daughter marry a rich Taiwanese doctor.” But then, in an act of practicality, she amends her prayer: “A Taiwanese businessman would be acceptable. Acceptable but not ideal.”

I would’ve settled for an acceptable but not ideal date to my Spring Fling.

Belly-button Grandmother yanks her thumb out of my belly button and calls sharply, “Ho Mei-Li!”

The door opens immediately. Mama’s face tightens as she peers accusingly at me. Her permed hair is a damp halo around her furrowed brow. She glances at me and speaks in a rapid Mandarin so that I can’t follow what they’re saying.

I tug my T-shirt down and sit up. Who needs a translator when I see my mother’s frown and the shake of her head as Belly-button Grandmother chatters?

“Be-gok lan?”

Mama says, slipping into Taiwanese in her shock.

Belly-button Grandmother nods once, solemnly, even though she doesn’t understand Taiwanese. Whatever the language, I have no problems divining what’s being predicted here. According to my navel, I am going to end up with a white guy.

Mama glares at me:

Oh, you making a big mistake.

I walk to the window overlooking the International District, all crowds of black heads and neon lights. And I’m surprised that I just want to go home. Not out to my favorite Chinese restaurant, not even to the dance, but to my bedroom.

I touch my belly button. Maybe there is magic in there after all.

I know what I’d wish for.

As Mama and Belly-button Grandmother confer about my life, I rub my stomach three times for good luck, just as if I were a gold statue of a big-bellied Buddha.

Then I wish to be white.

Mama-ese

Mama-eseA

fter we collect my

big brother, Abe, who’s been poring over Japanese comic books in a

manga

store, Mama conducts the Chinese Food Census, her preferred method for selecting a restaurant. No studying of menus or trusting food critics for Mama. Instead, she stares into a window—never mind if she freaks out some poor diner who happens to be eating by said window—and tallies the number of black-haired heads inside a restaurant.

Her theory is straightforward and accurate: a high black-hair-to-blond ratio equals a good Chinese restaurant. High blond-to-black-hair equals food fit for pigs. I would have said dogs, but some people are under the misconception that all Asian people eat man’s best friend. We don’t. The only part of a dog I have tasted—by accident when I laughed while within licking distance of a golden retriever—was its slobbery tongue. However, inquiring minds want to know why we don’t hear people retching over the Rudolph-the-Red-Nosed-Reindeer-eating Norwegians or the whatever-the-hell-is-haggis-chewing Scottish.

Mama squints, shakes her head and scurries on, passing one restaurant after another. Finally, we’re sitting inside a Cantonese restaurant, packed with huge families, loud chattering intergenerational micro-villages. Our tiny family of three is a raft bobbing in a sea of Chinese conversations. A lone wave of English washes over from a Tourist Family, who are goggling like they’ve flown into Shanghai, not Seattle. Over in the corner by the fish tank, a herd of kids pounds on the aquarium, but the fish don’t swim away. I want to warn those cooped-up fish,

Beware of the Big Net.

Since fighting is futile, I don’t say a word.

Above the Mandarin and Cantonese, the clicking of chopsticks, the pouring of tea, Mama and I face off. We sit across the table from each other like two generals negotiating a delicate truce. At the far side is Abe, Switzerland in this battle of words. His dark eyes are locked on the dumbed-down English menu like he’s cramming for a final tomorrow in a class I could teach: Multiple Disorders of Dysfunctional Half-Asian Families.

“You going to summer camp,” Mama announces to me without looking down at her menu.

My heart stops. I can already picture the hell that my mother wants to send me to. You can bet that this is no camp with horseback riding or archery. There’ll be no in-depth sessions on anything remotely cool, say multidimensional printmaking or Italian cooking. My stomach starts making worrisome gurgling noises as I recall the “accelerated learning programs” Mama made me apply to for the summer.

All I know is that I better parry back, and fast. “No, I’m going to be working. Remember, you said I had to get a job this summer.”