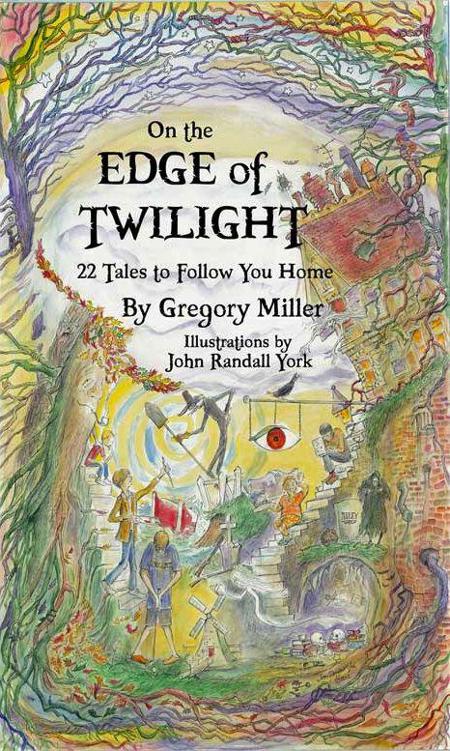

On the Edge of Twilight: 22 Tales to Follow You Home

Read On the Edge of Twilight: 22 Tales to Follow You Home Online

Authors: Gregory Miller

Table of Contents

On the Edge of Twilight:

22 Tales to Follow

You Home

Gregory Miller

Illustrated by John Randall York

Praise for Gregory Miller

“Gregory Miller is a fresh new talent with a great future.”

--Ray Bradbury

“Gregory Miller’s prose has a luminous clarity rarely seen in a postmodern age where mysterious opacity is often touted as a virtue…He addresses the reader in a poetic language that is translucent, heartfelt, and wise.”

--Roderick Clark, Editor/Publisher of

Rosebud Magazine

“The small town life depicted in

The Uncanny Valley

is in many ways familiar and comfortable territory, but each story demonstrates that something unnatural lurks beneath the surface. As the stories coalesce to form a larger narrative, the perversity builds…On its own, each individual anecdote is merely curious; as a collective, they become morbidly sinister.”

--Booksellers Without Borders

“Miller’s intriguing premise and incredibly creative stories had me completely enthralled…one of the best eerie books I’ve read.”

--

Book Matters

, reviewing

The Uncanny Valley

“[

The Uncanny Valley

] is an inspired and original idea, breathing fresh life into a popular and revered genre.”

--Novelist and critic Daniel Cann

“Gregory Miller’s tales in

Scaring the Crows

are wonderfully dark, wonderfully various, and wonderfully wrought.”

--Brad Strickland, award-winning author of the

Grimoire

series.

“

Scaring the Crows

is a delightful collection. The stories are chock full of heart and description, and you’re left amazed that you could grow so attached to the quirky and often quite likeable characters in such bite-sized works.”

--

Hawleyville Reviews

“It’s easy to imagine [

Scaring the Crows

] being done by one of the old greats… This book is a treat.”

--

Book Reviews Weekly

In Memory of Ray Bradbury:

Mentor,

Teacher,

Friend,

with “love to the end of the 21

st

century.”

And for Zee, always and forever my Big Sis.

Acknowledgements

These stories were first published in the following venues, and are reprinted with permission:

“The Forest and the Trees,” “Time to Go Home,” “The Leasehold of His Days,” and “Supper-Time” in

The Sounding of the Sea: Five Tales of Loss and Redemption

. Lame Goat Press, 2010.

“The Saver” in

Potter’s Field 4

. Sam’s Dot Publishing, 2011.

“Shells” in

Three Stories (Vol. 1, No. 2).

OmicronWorld Entertainment, 2009.

“Par One” and “A Quick Break” in

Flash!

Static Movement, 2010.

“The Subject” in

Halloween Frights II

. Static Movement, 2011.

“The Return” in

Cup of Joe: Coffee House Flash

. Wicked East Press, 2011.

“The Key” in

Caught by Darkness

. Static Movement, 2010.

“Miss Riley’s Lot” in

Day Terrors

. The Harrow Press, 2011.

“Wood Smoke” in

Don’t Tread on Me: Tales of Revenge and Retribution

. Static Movement, 2010.

All other stories are original to this collection.

Finally, many thanks to Laury Egan and Tracy Fabre, for their thoughtful and painstaking editorial work and suggestions.

Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea.

—Dylan Thomas

Houses are not haunted.

We

are haunted.

—Dean Koontz

The Forest and the Trees

An abundance of forest borders Still Creek, but the small expanse of Still Creek Wood stands alone on the hill above my grandparents’ house. When I was young, Grandpa and I walked it every time I visited, even the last Christmas before he died, when he knew his heart was almost kaput and that any kind of outdoor walking was full of risk.

Unlike other forests that fringe town, there is never any trash in those woods, and hunters shy away from them. So Grandpa, who spent his youth working underground in the coal mines and his middle age teaching in classrooms, liked it up there, beneath the rustle of leaves and the sigh of branches. I’ve almost forgotten what that feels like: to be at ease in a quiet place you know is safe.

But it wasn’t always safe.

Four months after Grandpa died, in early May, right after my tenth birthday, Grandma sat me down with a piece of pumpkin pie and a glass of milk.

“Promise me you won’t go in the forest behind the house anymore,” she said. “Promise me you’ll leave Still Creek Wood well enough alone.”

I was surprised. “But I go in there all the time! And it’s the easiest way to get to the top of Still Creek Hill and over to the fairgrounds.”

Grandma stood firm. “That may be, Dennis, but it isn’t safe without your Grandpa. When you’re older, maybe I’ll explain.”

“Why not now? Why not for sure?”

“Just promise me. There are plenty of other places around here for a boy to explore.”

Well, I promised, even though I didn’t understand why. But I was ten, and I was told not to do something for my own good. What choice did I have? On the final day of the visit, hours before Mom and I started the three-hour drive home, she and Grandma went to Plumville to shop for crafts, and I stayed behind and did what I promised not to do.

I trotted up the back yard, past the flower garden under the maple tree, the flagstone walk, and the tool shed; past the burn pile, the three pine trees, and the old stone spring, until the long, wet grass of May became strewn with mildewed leaves and the forest loomed.

When I was very young, I thought there were man-made trails through Still Creek Wood, but as I got older I realized they were due to the natural placement of the trees. The trees grow tall and full without being smothered. Their branches intertwine but don’t compete for sunlight or air. No one made the trails. The trees did.

I followed a familiar path. Grandpa and I used to walk to the point where the forest ends atop the hill, then over to the western edge bordering Mr. Collins’ wheat field and back down to the yard. I went that way, since it made me think of Grandpa; only three months after his death, I had already come to realize the importance of routine as a method of remembering what has gone away.

For the most part the forest floor was dark, but sunlight broke through in places, and every so often I stopped to look up at the fractured rays that filtered down among the softly groaning boughs high above. I enjoyed the rustle of leaves and the noise of branches clacking gently together. Far off, I could hear the bells of the church on Pugh Street tolling the time: five o’ clock.

The only evidence of human presence within the forest was (and still is, so far as I know) toward the bottom of the western edge, a couple dozen yards from Mr. Collins’ field, where an old set of seven stone steps had been hauled out from an abandoned barn many years before. Whenever Grandpa and I walked in the woods, we’d always stopped by them. I don’t know why they fascinated me. Maybe it was seeing stairs in a place where they didn’t belong. Maybe it was seeing the stairs slowly, gradually begin to look more and more like they

did

belong, as moss, fallen leaves, and weather did their work. Regardless, they had been in the forest since before I was born, lying among the trees but not touching them, not

of

them, and I liked their strangeness.

But this time, as the angle of the falling sun sent long shadows reaching out behind all standing things, I realized something had changed.

I came to where the steps should have been… and couldn’t find them. For a few unhappy moments I thought maybe someone had finally broken them up or taken them away again, but after circling the area carefully, eyes focused on the closely-patterned landscape, I suddenly realized, with a start, why I’d missed them.

The stairs now leaned against a full-grown oak tree, forty feet tall if an inch. Its straight trunk gave way to branches that arched over my head like open arms. Now the stairs rose, upright, to the lowest branch of the tree, supported by the rough, solid trunk.

I walked around the tree several times, trying to tell for sure whether I was in the right spot. Yes. A flat boulder Grandpa used to rest on still sat in its usual place amid a bed of fern just a spit away, rain-stained and covered with pale green lichen. A squat poplar still grew nearby as it always had.

My heart raced and I remember letting out a thin sigh, confronted for the first time in my life with something that didn’t make sense and couldn’t be explained.

Somehow, in the five months since Grandpa and I had taken our final walk together, an oak had grown from nothing to full, stately height, moving the steps with its growth until they climbed, with rediscovered purpose, to meet its boughs.

I crept over to the steps, ran my hand over the worn, moss-covered slab, and clambered up the old stone cuts. Reaching the top, I grabbed the oak’s lowest branch, hoisted myself up, twisted around, and then, with a gasp and a grunt, plunked down on it.

Above and around me the leaves of the tree rustled softly. I looked about, impressed by the height and view, hardly realizing how comfortable the crook of the branch had become. And as I sat there, I gradually became aware of my own feelings: for the first time since bitter, cold February, I had allowed the preoccupations of worry and grief to fall away, lulled by the murmur of sap-blood and gently shifting leaves. The great, crushing wheel of loss had been halted, if only briefly. Security and comfort had taken its place.

A short time later the town bell tolled six. Mom and Grandma would be returning from Plumville soon. Jolted, I felt for the top of the stone with my feet, and, finding it, trotted back down the steps and broke into a jog. The back yard was close, only a hundred yards away. It would just take a minute, and I’d be home. Just one minute—

The feel of rough, hard fingers digging into my arms is one I would like very much to forget, but the memory will not fade. As I was lifted off the ground, shrieking and hollering, legs pumping the air, it flashed through my mind that Grandma had been

right

to warn me, that I should have listened, and that promises should never, ever be broken…

I remember the strong, heady smell of pine sap and the creak of the limbs that lifted me, high, high, oh, a good fifteen feet off the ground, and it wasn’t long until I had thrashed my way around and finally saw what held me.

The pine tree was massive, dark, and ancient. I’d walked past it with Grandpa many times but never stopped to look close. It was one of those trees that always looks dirty, and not very good for climbing, and even kind of scary in an indefinable sort of way. But now I knew that the deepest, gloomiest part of the tree, high in the upper boughs, had never before revealed itself. I could sense it: a brooding night of death-preserving amber sap, tangles of brittle twigs, and the soft, warm egg sacs of spiders. It was a blackness palpable, a deep gulf—and, having sensed it, I knew that if I didn’t free myself from those hard, creaking branches I would come to know it well, know it intimately, and that such knowledge would be enough to darken my world forever.

With a massive, desperate twist, I wrenched myself away, dropping to the ground with a

thud

that didn’t break anything but left my shoulder purple, yellow and brown for weeks to come.

Freed, sobbing, I ran.

And I never explored Still Creek Wood again.

* * *

But I did go back to Grandma’s. I went back often. And it was just before the Spring Break of my senior year in college that my psychology professor gave us the assignment of conducting “20 Questions” with an older relative. “If done properly it will provide an illuminating picture of how the lives of older generations differ from the adolescents you will soon be teaching yourselves,” she told us. “No ‘yes’ and ‘no’ questions in this game, though. Ask open-ended questions and encourage your subject to elaborate.”

So that’s what I did.

Grandma was eighty-four that year. Her eyesight was beginning to fade, but she was still sharp as ever and a willing subject. I asked about her courtship with Grandpa during the ’20s, about her parents, about school conditions and grading and cars and long-dead relatives, about World War II and ration books and the Great Depression, about meeting FDR during a Gettysburg speech and attending, when she was a very little girl, the last public hanging in Pittsburgh. After an hour, I’d exhausted my set of prepared questions and started to wrap things up, but she didn’t make any motion to indicate we were through. Instead, she nodded at the paper and said, “There’s only nineteen questions there. You still have one to go!”

I looked down at my paper in surprise, realized she was right, and sat back in my chair to think. I heard the steady breath of spring wind as it rattled the kitchen windowpanes. Listening harder, I noted the distant sigh of branches. “Tell me why Still Creek Wood is dangerous,” I said abruptly. “Tell me why I shouldn’t go there.”

Grandma glanced up sharply. For a moment her fingers tightened their grip on the armrests of her chair, then slowly, slowly relaxed again.

“It isn’t something people speak much about,” she said.

“I understand,” I said quickly, embarrassed. “We don’t have to talk about it. I shouldn’t have said—”

Grandma threw her arms up with a great sigh. “Oh, of course you should have. You’re an inquisitive soul like your Grandpa and, if I do say so myself, like me. It’s in the blood. And you have a right to know, as I see it, even if you don’t live in town.”

Something burned behind Grandma’s rheumy eyes: a knowledge that had grown ripe for imparting.

“Have you ever noticed,” she asked, “how those woods are never touched by loggers?”

“I guess I figured the trees were protected. You know, by the town board or something.”

“But no trash? No vandalism, no hunters? State-protected wilderness isn’t well guarded, kiddo. Not in places like this.”

I thought about it for a moment, realized she was right, and said so.

“All these years, the town filled with trouble-seeking boys, vandal teens, and no-good adults, and Still Creek Wood never became a club house for any of them,” Grandma continued.

“So why not?” I asked.

“Because the trees protect themselves,” she said simply.

And I nodded, because I knew it was so.

* * *

Like a wave held back since that long-ago day when Grandpa’s loss was fresh, childhood still slipping away as the true nature of death sank in, I told Grandma everything I remembered, much of it feeling like an old half-recalled dream until my words made it real again.

And, finishing some time later, I looked up to see Grandma’s cheeks were wet.

“Oh, child,” she said. “You should have listened. You should have stayed away.”

“Tell me why,” I said. “Make me understand.”

Grandma sipped gingerly at her iced tea, heeding the cold, and said, “A fair number of old folks like me know what I’m about to tell you, though we each came across the truth in different ways. In my case, and your grandpa’s, it was our first next-door neighbor, Mr. Adams, who let the cat out of the bag. He was old when we were young, and had seen things in Europe during the First World War that drove him to drink. When he drank he often came over to talk with your grandpa. I didn’t like it at first, but Mr. Adams was never violent or rude, just liked to talk, and one night I overheard him say, ‘If you walk in Still Creek Wood enough times, you’ll notice how none of the old trees were ever young, and none of the young trees ever grow old.’”

Grandma leaned forward. “He was right, you see. If you ever go up there again—though I’m not saying you should, even if you

are

older now—you’d see the same young saplings in the same places, same height, same branches, that were there when you were a child. There would be a few more, since Mrs. Forester had a still-born baby two years back and that sweet Schretengoss child died of leukemia, but besides them the saplings in the forest would be the same. And the older trees? The ones when I was young are the same as the day they appeared, but have since been joined by many, many others.”

I shook my head. “What do you mean, ‘appeared?’”

“Just like you saw all those years ago,” Grandma said. “A tree that hadn’t been there before, full-grown, pushed those old steps up so you could swing your legs from the lowest branch.” She paused, allowing me to piece everything together so I could say it back to her, paraphrased and simplified, evidence of my understanding.