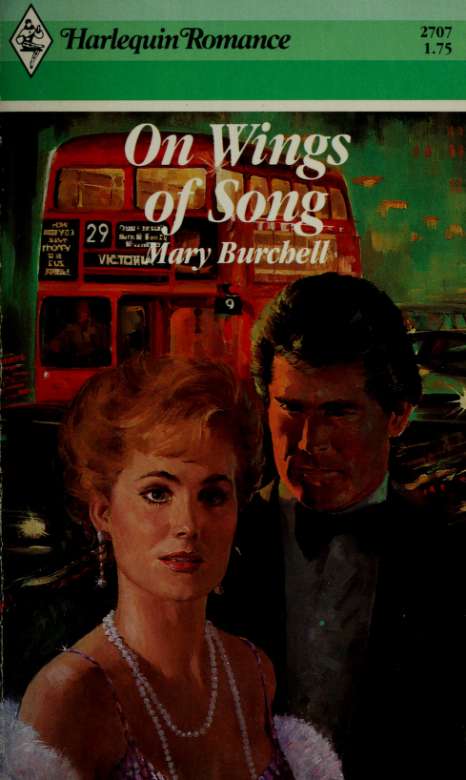

On wings of song

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

CHAPTER ONE

If she had not lost her footing, running to escape the sudden downpour of rain, Caroline would never have noticed the ring. It was lying there on the grass verge beside the path and, as she struggled to her knees, wet and a good deal shaken by her fall, she realised that the something sparkling there was not just another raindrop. It was a diamond. A large diamond at that, most beautifully set in a ring of undoubted distinction.

*It can't be real!' was her first thought as she reached for it. But she knew it was. If it had been just any old diamond ring she might have been mistaken. But not with this one. The light which struck back from the stone proclaimed its proud identity, and instinctively she slipped the ring on to her finger instead of thrusting it into her handbag.

Then she scrambled to her feet, ignoring the pain in her wrenched ankle, and looked around the deserted paths of St James's Park. In the distance the last of the homegoing crowds were nmning into Piccadilly and the shelter of buses or Underground. Even if she could have caught up with them, which was doubtful, a general query of *Has anyone lost a diamond ring?' would almost certainly result in an embarrassing number of claimants, from which she could not possibly identify the right one.

She would go to the police in the morning, she

told herself, or look for some newspaper annovincement in the 'Lost and Found' column. At the moment all she wanted was to get home and into dry clothes. So she made for her bus, and was thankful to sink into the one imoccupied seat.

By the time she put her key into the lock of the front door she was feeling less sick and shaken, but a wave of irritation swept over her as Aunt Hilda called out predictably, *Is that you, Caroline?'

Not for the first time she resisted the temptation to ask crossly who else it could be, and went into the front room, where her aunt was sitting idly flicking over the pages of a magazine in a pleasant state of inactivity.

*I was just thinking of putting on the oven,' she observed, which was palpably untrue. *But since you're on your feet, dear, you might do it. Jeremy won't be in until late, so it's just you and me.'

Obviously Aunt Hilda had not noticed that Caroline was wet, nor that she was limping. But, like most women who enjoy a certain degree of poor health, Hilda Prentiss was totally indifferent to any distressing symptoms other than her own.

Caroline went through into the kitchen, completed the simple preparations for the evening meal already set in motion by their invaluable home help, and only then went to change into dry clothes. For some reason which she did not seek to explain to herself she still retained the ring on her finger when she returned to the dining room.

'Did you get wet?' asked her aimt, glancing out at the pouring rain.

*Yes. As a matter of fact, I fell down in a puddle.'

'Oh, dear, too bad,' was the philosophical reply. *I myself nearly had a fall this morning. I must get Jeremy to fix that rug in my room. I was saying to Mrs Glass only yesterday that I might

have a nasty fall if ' then she stopped

suddenly and exclaimed, 'Where on earth did you get that ring?'

'I found it—in the Park—when I fell down.'

*You found it? But it's real, isn't it? Let me have a look at it.'

With an odd sense of reluctance Caroline drew the ring from her finger and handed it over.

*Yes, it's real all right.' To Caroline's annoyance, her aunt breathed on it and rubbed it on her sleeve. *It must be worth a fortime! Why didn't you take it to the police?'

'Because I was soaking wet and I'd hurt my ankle. And anyway, I didn't know where the nearest police station was.'

'Someone's going to be dreadfully upset about losing a ring like that,' her aunt said reproachfully. 'Didn't you think about the poor owner and how she must be feeling?'

'No.' Caroline replied obstinately. 'I thought about how tired and wet / was, and that I would do something about the ring tomorrow.'

Her aimt clicked her tongue reprovingly.

'If it had been me I shouldn't have been able to think of anything but that poor frantic owner,' she declared. And since Caroline knew that her aimt truly believed this was so, she felt her usual good humour restored.

'Well, Aimtie,' she smiled, 'I'll bestir myself

tomorrow to do everything I can to find the owner.'

Then she held out her hand firmly for the ring, which was rather reluctantly returned.

*Did you say Jeremy would be late?' she asked, anxious to change the subject.

*I expect so. He went to an evening audition.*

*He dicR^ Caroline's tired face lit up with sudden animation. An animation which changed her from a sensitive, thoughtful looking girl to a vivid, near beautiful one. *Oh, Aunt Hilda! Something really important, do you mean?'

*He didn't say. I asked him, of course. I reminded him how it frays my nerves not to know. But he just told me to wait and see. I suppose so many disappointments have made him secretive,' she added plaintively. But then she smiled indulgently, for her son Jeremy was her idol—a point of view which Caroline completely understood.

Indeed, from the day when she had come—a scared, bewildered orphan—to make her home with Aunt Hilda and Jeremy, she had, quite simply, loved her cousin better than anyone else in the world.

She had been no more than eleven at the time, still stunned by the death of both her parents in a car crash. And Aunt Hilda, to whom family ties were of almost sacred importance, had, to her credit, imhesitatingly offered a home to her orphaned niece. If she had been to a certain extent influenced by the quite substantial inheritance which went with the niece it would be imjust to blame her. She was, after all, herself a widow living on a small pension, and Caroline

and her inheritance had been most usefully absorbed into the family.

In return, she was provided with a comfortable if impretentious home, her aunt expending upon her some degree of good-humoured affection—so long as no undue demands were made on her energies or sympathies.

Above all, Caroline was blessed by the companionship of Jeremy. He was sixteen when she joined the family, a good-natured boy with an imexpected capacity for imaginative sympathy, which prompted him to put himself out to discover ways of comforting the disconsolate child, and interesting her in various facets of her new life.

That most of these concerned himself closely was inevitable, and she became first his little confidante and then his wholehearted partner in plans for the future. His future, naturally.

Presently the years when he would inevitably leave home to go to college began to loom distressingly near. But then something wonderful happened. On the strength of a good tenor voice Jeremy obtained a grant to pursue his studies at one of London's leading music colleges. There was therefore no need for him to leave home after all—and Caroline was happy.

*It will be a long time before he earns anything like a good living,' Aimt Hilda had said, pouring unwelcome cold water on the dreams which Caroline shared with Jeremy.

*What does that matter?' Caroline had retorted stoutly. 'Families of great artists have usually had to make a few sacrifices.'

Aunt Hilda, who didn't think much of

sacrifices unless someone else was making them, replied that that was all very well, but household bills had to be paid even by the families of potentially great artists.

*We'll manage/ Caroline had declared. 'I still have a bit of my capital left. And I'll soon be earning my own living.'

So a little more was scooped out of the diminishing capital, and presently Caroline was indeed earning her living, as secretary to Kennedy Marshall, an up-and-coming musical agent. She regarded this appointment as a gift straight from an understanding Providence, for what could be more helpful to a budding tenor's future than a good agent somewhere in the background?

Things did not, however, work out quite as she had hoped. At first she was a good deal frightened by her employer, who had a quick temper which he usually—but by no means invariably—kept in check. People who liked him described him as dynamic; those who did not said he was arrogant. Both, however, had to admit that he possessed to an unusual degree that curious blend of artistic vision and business acumen which tends to make the highly successful agent in the world of music and the theatre.

To Caroline the astonishing thing about him was his vitality—a vitality which seemed to show even in the waves of his strong, almost black hair. Living, as she did, with the completely negative Aimt Hilda and the charming but less than forceful Jeremy, she had never before come in contact with such a positive human force. It was like meeting with a strong wind on a brilliantly

sunny day, and it was both intimidating and oddly invigorating.

Although he was a big man there was a sort of animal grace about him, very noticeable in his quick but always purposeful movements; and Caroline, who was apt to notice people's eyes and hands, was sometimes surprised by the changing expression of the former and the unusually good shape of the latter.

She gathered that he was satisfied with her work, but most of their conversation remained on a strictly business level. He shouted at her sometimes, but occasionally apologised later, and on very rare occasions would praise her work with a sudden flashing smile which warmed her heart.

Altogether, however, it was more than six months before she ventured to inform him that she had a very gifted cousin who sang.

*Most people have,' was the discouraging reply. 'What is she? Coloratura soprano? They tend to be—or to think they are.'

'No, no. He's a tenor,' Caroline hastened to assure him.

Kennedy Marshall pulled a face at that and said. 'Even worse! You would hardly believe the number of forced-up baritones who expect me to get them leading positions as tenors.'

She bit back the indignant retort that Jeremy was a real tenor—^which in point of fact he was— but the effort made her look flustered and self-conscious.

'Well?' He tipped back his chair and regarded her with a sort of exasperated amusement and said. 'You'd better make the whole confession. I

suppose this is all leading up to the announcement that you yourself have singing aspirations?'

'Oh, no!' exclaimed Caroline. Then she blushed scarlet, for she was by nature a truthful girl. 'At least '

'Yes?' He smothered a yawn and reached for a file.

'Nothing,' she told him rather haughtily, and she turned away to the filing cabinet, unaware that he regarded the back of her well-shaped head with a touch of amused curiosity.

In asserting that there was no more to admit Caroline believed she was stating no less than the truth. In the strict sense of the term she had no urgent singing aspirations. She had a voice, it was true, an unusually lovely one. But she hardly presumed to think of herself with a professional career. That was Jeremy's part. He it was who was destined to bring fame and fortune to the family. His was the career which was to be nurtured, guided and finally presented to an admiring world.

To enter into competition with him as he struggled up the first rungs of the ladder of fame would be base disloyalty, and no one felt that more keenly than Caroline. Consequently, it had been agreed between them during the last year or two that there was no room for more than one voice in their family.

'Even one first-class voice in an ordinary family strains most people's credulity,' Jeremy had explained. 'Two would sound totally bogus. Once I'm established, of course, I'll help you along—I promise that. But at your age you can afford to wait a bit, whereas I can't. You do agree, don't you?'

Naturally she had agreed, and even at home she spoke very little about her own singing lessons. They were in any case not very distinguished. Nothing to do with any music college—just twice a week with the seventy-year-old Miss Naomi Curtis, who had been in musical comedy in her youth. But the fact is that in Miss Curtis's youth a pretty well based technique was required in order to sing even in musical comedy—a stroke of good fortune of which Caroline was quite unaware at this point.

'I suppose you want me to hear this cousin of yours?' Kennedy Marshall suddenly broke in again on Caroline's thoughts.

'Would you?' She turned upon him such a dazzling smile that he blinked slightly.

*No. At least, not here and now,' he countered rather disagreeably. 'One of these days, maybe, but at the moment I've got other things on my plate. I suppose now is as good a time as any to tell you. The fact is we have a merger going through in the near future, Caroline.' He only called her Caroline when he was in a good mood. *It will be with Dermot Deane.'

' The Dermot Deane?'

'I'm sure he would regard that as the right way of putting it,' her employer griimed almost boyishly.

'But he handles all the top people, doesn't he? He has done for years.'

'That's the rub for poor old Dermot—"he has done for years". He's getting on a bit now and finds the continual travelling and the strain of managing what you call the top people rather more than he can take. He had a heart attack

some months ago, and though he made a good recovery his doctors told him he must ease up a bit unless he wanted more serious trouble.'

'And he chose to merge with our company?'

*I think he would prefer to describe it as absorbing us into his company,' her employer corrected her. 'Anyway, he needed a partner with the kind of energy and vitality which he himself once had.'

'You, in fact?' Caroline smiled back at her employer with a sort of naive satisfaction which evidently amused him.

'It seems so,' he agreed, with an air of modesty which was almost totally spurious.

'Does that mean that you will be handling people like Torelli—and Nicholas Brenner, and Oscar Warrender?'

'Could be. The transfer will be a delicate one, and we shall need all our diplomacy and tact.' She thought it was nice of him to say "we", until he went on. 'So don't try to push your singing relatives into the picture, will you? I'll listen to the budding tenor one of these days, but / will say when.'