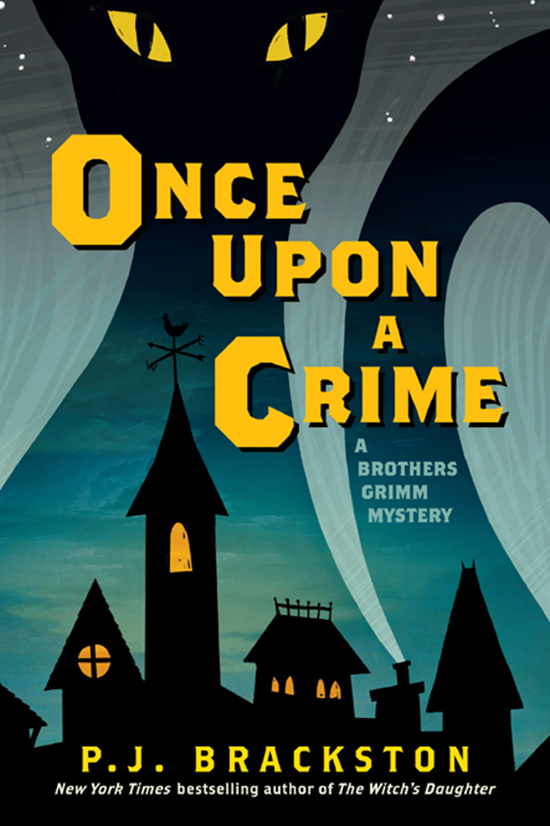

Once Upon a Crime

Authors: P. J. Brackston

O

NCE

Â

UPON

A

Â

C

RIME

A BROTHERS GRIMM MYSTERY

P. J. BRACKSTON

PEGASUS CRIME

NEW YORK LONDON

For Becky

ONE

A

very long time ago, in a land far, far away, a lonely giant sniffed loudly as he wept. The mournful sound echoed around the cave that was his home, his breathy sobs causing the flames of the torches to gutter and the shadows in the damp space to jump. His grotesque form cast its own vast blackness against the dripping stone walls, hideous even when reduced to silhouette. He wiped his nose with the back of his lumpen hand, spreading a layer of silky grayness across his face. From deeper within the labyrinthine rooms of the cave came the plaintive cries of smaller, frailer beings. The giant paused in his weeping; paused to listen. A frown rearranged his features into an expression of quake-making ferocity.

“Be quiet,” he whispered, but the cries continued.

“Be quiet!” he roared, bringing his great fist down with such force that the table beneath it splintered into kindling, and the cries ceased.

Gretel lay on her daybed and tried to ignore the hammering on the door. It was almost as loud as the hammering inside her head. She had spent the previous evening drinking far too much with Hans, in a rare moment of sibling solidarity, and a hangover of impressive tenacity had taken up residence behind her eyes. Gretel groaned. Both hammerings continued. She pulled a silk cushion over her head, silently cursing Hans, vodka martinis, and people who came knocking.

“Go away!” She moaned. “Whoever you areâI don't want to buy anything, I haven't any rags, or antiques of unnoticed value, and I most definitely do not want to be saved.”

If anything, the knocking increased.

“Hell's teeth!” Belching fruitily, Gretel flung the cushion aside and dragged herself from the tapestry daybed of which she was so fond. She paused in front of a mirror to tighten the cord of her house robe, the better to hold together her otherwise unclothed body. She winced at the pressure on her not-inconsiderable belly. Her breasts sat heavily atop her heavy stomach. She sighed at the landscape her figure presented: an Andean range of mountainous peaks and unfathomable valleys that no amount of dieting could level one inch. She had long ago accepted that she was a big woman. Not just fat, but big.

Big bones, big features, big voice, big hair. Big appetite. Gone was the flimsy child who had trailed lost through the woods with her brother. Gone was the leggy teenager who had graced the stage at the ludicrously posh school to which the king had

later decreed she be sent. Gone, even, was the voluptuous girl in her twenties who had, at least, appealed to a certain type of man. Here, instead, was Gretel the thirty-five year-old woman, with the physique of a wintering grizzly bearâand almost as much facial hair, should she miss one of her frequent waxing appointments.

She strode past the mirror in the hall, determined to ignore its critical gaze, cleared her throat noisily, spat expertly into the spittoon beneath the aspidistra, and yanked open the door with a “What the bloody hell do you want at this hour?”

“It is nearly four o'clock,” replied the neat, diminutive figure of Frau Hapsburg. “My point exactly.”

“Are these not business hours?”

It was a fair question, a fact that served only to irritate Gretel further. She glanced up at the sign that hung in her porch declaring her to be

Gretel

(yes,

that

Gretel),

Private Detective for Hire

. She frowned, silently telling herself that a possible client meant possible money, and the coffers were worryingly low.

“You'd better come in,” she said, turning on a slippered heel. Frau Hapsburg followed meekly.

Gretel's office had once been the dining room, and still housed a fair collection of pewter candlesticks, tapering, if dusty, candles, tarnished napkin rings, an open canteen of fish knives, and needlework place mats depicting kittens frolicking with wool. It was the sight of one of the last that sent Frau Hapsburg into a fit of sobbing. Gretel recoiled. She disliked displays of emotion of just about any kind, but particularly the wet variety. The wailing and red-eyed bawling was quite revolting and she knew she must do something to make it stop. She cast about for a handkerchief, but could find only an ancient napkin. Too late she realized that what she had taken for an abstract pattern was, in fact, encrusted food. Frau Hapsburg seemed not to care. She blew her nose loudly.

“So”âGretel kept her manner business-like to avoid setting off another bout of weepingâ“what's this all about? Let's have it.”

“My darlings.” Frau Hapsburg's voice was hoarse with despair. “My poor darlings have been taken!”

“Your children? Somebody has taken your children?” Gretel leaned forward, feeling herself perk up a little. A good kidnapping could take time to solve and prove lucrative.

“Alas, I have no children.” Frau Hapsburg put her right. “I am speaking of my cats.” She swallowed another sob. “My poor, poor pussycats.”

Gretel slumped back in her chair, causing it to creak alarmingly. “Cats,” was all she could be bothered to say. She had never seen the point of pets and she particularly disliked cats. There had been far too many instances of them stepping happily on silk-soft paws into the role of witches' familiars. She took a deep breath, tasting the fur on her tongue, and tried to muster sufficient enthusiasm to make some money out of the sad creature who sat before her. “They've gone missing, then?”

Frau Hapsburg was transformed by fury. “Not missing,

taken

! Taken, I tell you! Taken! People keep saying they've wandered off. âCats go missing all the time,' they say. âIt's in their nature,' they tell me. Well, I know my cats. They never wander. Never! Somebody has taken them, and I want you to find out who it is, find out where they are, and bring them back to me.”

“Right. I see. And when did these . . . animals disappear? That is”âshe held up a hand to stave off Frau Hapsburg's protestationsâ“when were they taken?”

“Two nights ago. I've had not a minute's peace since.”

“I see,” said Gretel again. Her client's bottom lip began to wobble once more. “Of course, I'm pretty busy at the moment, heavy caseload and all that. It'd be hard to fit you in . . .”

“Oh! Please say you'll help me. I've no one else to turn to, and the kingsmen aren't interested in the slightest, heartless things.”

Gretel pictured Kingsman Kapitan Strudel's sour face at the thought of lowering himself to search for AWOL felines. The image it presented made her feel like smiling for the first time in days. She remained straight-faced, however. There was money to be discussed, and money was a serious matter.

“Well, it would mean putting other things on hold, you know. My fees would have to reflect the priority given to your case, and then there's the inconvenience to my other clients.” Even Gretel could hear the scraping of a trowel behind her words.

“I'll pay extra. Whatever it takes.”

Much to Gretel's delight, Frau Hapsburg began ferreting in her carpetbag and extracted a colorful wad of notes.

“How much do you want?” she asked.

Gretel found herself licking her lips. She spoke quickly. “Ah, yes, that'd be my usual retainer plus thirty percent, with expenses on top, naturally, with, say, fifty percent up front, daily reimbursements on incremental increases, as per norm, and the balance on successful completion. Would that suit?”

Frau Hapsburg looked fittingly puzzled but nodded vigorously, pushing what money she had brought with her across the cluttered table to Gretel.

“Excellent! Excellent.” Gretel made a pretense of counting the cash before attempting to stuff it into her corset, remembering she wasn't wearing one, quelling instinctive panic at having to let go of the notes, and pushing them into a nearby biscuit tin, snapping on the lid, and snatching up a pen.

“Look,” she said, “I'd better come to your house. See what I can see.” She tugged a coal bill from a precarious pile of papers and began to scribble on the back of it. She took down the

necessary details and ushered Frau Hapsburg out, promising she would call on her within the hour.

The small town of Gesternstadt might have been viewed by many as a charming example of all that was best in Bavaria in 1776, but it had about it a sham friendliness Gretel considered despicable. It wasn't just the twee architecture, though that was bad enough, with its picturesque wooden houses, shuttered windows with flower-filled boxes, low eaves, and wobbly chimneys, each and every one of them, in Gretel's opinion, sugary enough to induce diabetes. No, it was more than that; it was the cheery waves, the casual how-are-yous, the genial whistling of the workman, and the broad smiles of the shopkeepers. None of it genuine. Where had these good neighbors been, all those years ago, when Gretel and Hans had been led into the woods and left to the wolves? Where had they been when their stepmother had claimed to have sent them off to summer camp, while their father stood beside her, red-eyed and haunted? Where had they been then, she wanted to know.

The air was warmed by a precocious spring, but still carried its habitual Alpine nip. The dark woods to the east of the town sheltered it from the fiercest winds, but the influence of the mountains to the west, beyond the verdant high meadows, made sure no sensible person ventured out without a vest before June. Gretel considered herself sensible in most things, but as far as she was concerned fashion was not something that could be compromised in the name of good sense. Admittedly, most of her days were spent slopping about the house in her dressing gown with nary a care as to how she looked. But on the occasions when she could be bothered to get dressed, vanity kicked in. Labels counted. Reputation was vital. Kudos and cachet were paramount. It mattered not one jot to her that there was no one within fifty leagues of Gesternstadt capable of recognizing a Klaus Murren gown or a pair of Timmy

Chew shoes. She knew what she was wearing, that was what counted. Not for her the folksy comfort and traditional lines favored by most women in the town. Let them don appliquéd blouses, felt waistcoats, floor-skimming dirndl skirts and floral aprons, and dust off their pinafores on high days and holidays. In her teens, Gretel had shared a dorm with a girl from Paris, and her head had been forever turned.

The fact that most of the apparel after which Gretel lusted had been designed for women with shapes significantly and tellingly different from her own was one she chose to ignore. If the season demanded figure-hugging satin, then figure-hugging satin she must wear. She would be draped, head to stout ankle, in the stuff, regardless of its unflattering effects on her rolls and mounds. If brocade gowns, cinched at the waist, were to die for, then Gretel forced herself into them, even if she did end up looking more upholstered than clothed. If kitten heels were de rigueur for fashionistas elsewhere, then they were de rigueur for Gretel, despite the unfortunate overtones of trotters her broad feet presented when forced into the latest slender creations.