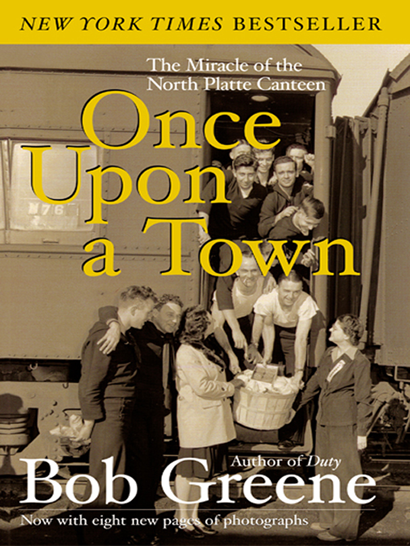

Once Upon a Town

Authors: Bob Greene

The Miracle of the North Platte Canteen

For Keith and Mary Ann Blackledge

On Interstate 80, three or four hours into the longâ¦

North Platte, Nebraska, is about as isolated as a smallâ¦

The Beatles and the Goo Goo Dolls sang consecutive songsâ¦

My first morning in town I awakened with the sunâ¦

“I had read about it in the paperâabout Rae Wilsonâ¦

On the weekend after I arrived in North Platte, theâ¦

There was a photo around townâan old black-and-white picture takenâ¦

I wanted to meet some of the businesspeopleâthe men andâ¦

Downtown, had you not looked at a calendar or atâ¦

Having immersed myself in the more wholesome facets of Northâ¦

There were islands in the South Platte Riverâlittle half-protruding grassâ¦

No Horses allowed.

The twin soundsâI was getting accustomed to hearing them. Oneâ¦

There were days when I discovered that entire lifetimes hadâ¦

“Downtown at the time was tremendously active, day and nightâand thisâ¦

I was beginning to understand just how the sandhillsâthe definingâ¦

There was an airport in town, although I had notâ¦

At dinner one night, while waiting for my meal toâ¦

With all the warmth and good feelings of the Canteenâ¦

“Knees up! Knees up!”

“You can't get back here on your own.”

Late in the afternoon, with sundown on its way, itâ¦

It was getting toward dark, and I knew I shouldâ¦

On Interstate 80,

three or four hours into the long westward drive across Nebraska, with the sun hovering mercilessly in the midsummer sky on a cloudless and broiling July afternoon, there were moments when I thought there was no way I'd ever find what I had come here to seek:

The best America there ever was. Or at least whatever might be left of it.

It wasn't some vague and gauzy concept I was searching for; not some version of hit-the-highway-and-aimlessly-look-for-the-heart-of-the-nation. This was specific: a real town.

But the news, as I was hearing it from the rental-car

radio on this particular summer's day, made Nebraska in the early years of the twenty-first century sound deflatingly like the rest of the continental United States.

In Sutherlandânot far from where I was headingâa man had come home from work to the rural farmhouse he and his sixty-six-year-old wife shared. The house, located on a dirt road about a mile from the closest neighbor, was in an area so quiet and sedate that there was seldom a reason to lock the doors. When the man arrived home, he found his wife sitting in a chair dead, with a gunshot wound to her head.

Two menâBilly J. Reed, twenty, and Steven J. Justice, twenty-twoâwere soon arrested. Prosecutors said they were wanted for the recent murders of an elderly couple in Adams County, Illinois. The men allegedly were fleeing across Nebraska, and stopped in at the farmhouse in Sutherland with the intention of robbing it. The men evidently selected the farmhouse at random, and allegedly shot the sixty-six-year-old woman to death just because she happened to be at home.

Also in Nebraska on this summer day, Richard Cook, thirty-four, was sentenced to life in prison because of what he did to a nineteen-year-old woman who was a college freshman.

She had been driving late at night when her car suffered a flat tire. Alone, she had pulled over to the side of

the road to try to change the tire. Richard Cook, driving on the same road that night, stopped his car as if to help the stranded young woman. He then assaulted her, shot her five times, and dumped her body in the Elkhorn River.

In Hall County, a man named Jamie G. Henry, twenty-four, was under arrest for allegedly using an electrified cattle prod to discipline his eight-year-old stepson. The cattle prod, according to sheriff's deputies, was of the kind designed to jolt two-thousand-pound bulls into obedience. Jamie Henry reportedly used it on the boy and his five-year-old sister; Henry also allegedly punished the boy by tying him tightly at his hands and ankles, and, during the winter, tying the boy barefoot to a tree and locking him out of the house in the cold.

That is what was going on in Nebraska on this summer dayâat least that is what was going on that had been deemed worthy of the public's notice. It could have been anywhere in the United States; the police-blotter barbarism of the news, the seeming soullessness of the crimes, had a sorrowful and deadening familiarity to them.

Yet once upon a time, in the town I hoped to reach by nightfallâ¦

Well, that was the purpose of this trip. Once upon a timeânot really so very long agoâsomething happened in this one little town that, especially on days like this one,

now sounds just about impossible. Something happened, in the remote Nebraska sandhills, in a place few people today ever pass throughâ¦.

Something happened that has been all but forgotten. What happened in that town speaks of an America that we once truly hadâor at least that our parents did, and their parents before them.

We're always talking about what it is that we want the country to become, about how we can save ourselves as a people. We speak as if the elusive answer is out there in the mists, off in the indeterminate future, waiting to be magically discovered, like a new constellation, and plucked from the surrounding stars.

But maybe the answer is not somewhere out in the future distance; maybe the answer is one we already had, but somehow threw away. Maybe, as we as a nation try to make things better, the answer is hidden off somewhere, locked in storage, waiting to be retrieved.

That's what I was looking for on this Nebraska summer afternoon, with the temperatures nearing one hundred degrees. The car radio continued to tell the dismal breaking news of the day, and I continued on toward my destination, a town with the unremarkable name of North Platte.

North Platte, Nebraska,

is about as isolated as a small town can conceivably be. It's in the middle of the middle of the country, alone out on the plains; it is hours by car even from the cities of Omaha and Lincoln. Few people venture there unless they live there, or have family there.

But before the air age, the Union Pacific Railroad's main line ran right through North Platte. In 1941, the town had little more than twelve thousand residents. When World War II began, with young men being transported across the American continent to both coasts before being shipped out to Europe and the Pacific, those Union

Pacific cars carried a most precious cargo: the boys of the United States, on their way to battle.

The trains rolled into North Platte day and night. A local residentâor so I had heardâcame up with an idea:

Why not meet the trains coming through, to offer the servicemen a little affection and support? The soldiers were out there on the empty expanses of midwestern prairie, filled with thoughts of loneliness and fear. Why not try to provide them with warmth and the feeling of being loved?

On Christmas Day 1941, it began. A troop train rolled inâand the surprised soldiers on board were greeted by North Platte residents with welcoming words, heartfelt smiles and baskets of food and treats.

What happened in the years that followed was nothing short of amazingâsome would say a miracle. The railroad depot on Front Street was turned into the North Platte Canteen. Every day of the yearâfrom 5

A.M.

until the last troop train of the night had passed through after midnightâthe Canteen was open. The troop trains were scheduled to stop in North Platte for only ten minutes at a time before resuming their journey. The people of North Platte made those ten minutes count.

Gradually, word of what was happening in North Platte spread from serviceman to serviceman during the war, and on the long train rides across the country the soldiers came

to know that, out there on the Nebraska flatlands, the North Platte Canteen was waiting for them.

Each day of the warâevery day of the warâan average of three thousand to five thousand military personnel came through North Platte, and were welcomed to the Canteen. Toward the end of the war, that number grew to eight thousand a day, on as many as twenty-three separate troop trains.

Many of the soldiers were really just teenagers. This was their first time away from home, the first time away from their families. On the troop trains they were lonesome and far from everything familiar, and they knew that some of them might never come back from the war, might never see their country again. And then, when they likely felt they were out in the middle of nowhere, they rolled into a train station and were greeted day and night by men, women and children who were telling them thank you, were telling them that their country cared about them.

The numbers are almost enough to make you cry. Rememberâonly twelve thousand people lived in that secluded town. But during the war, six million soldiers passed through North Platte, and were greeted at the train station that had been turned into a Canteen. This was not something orchestrated by the government; this was not paid for with public money. All the food, all the services,

all the hours of work were volunteered by private citizens and local businesses.

The only federal funding for the North Platte Canteen was a five-dollar bill that President Roosevelt sent from the White House because he had heard about what was taking place in North Platte, and he wanted to help.

It might have been a dreamâbut it wasn't. Six million soldiers who passed through that little townâsix million of our fathers, before we were born. And every single train was greeted; every man was welcomed.

It was a love storyâa love story between a country and its sons.

And it's long gone.

Â

That is why I was traveling across Nebraska on this sunbaked July afternoon.

There is no reason for anyone to pass through North Platte anymoreâthe jet age has done away with that. If a person wants to get from one end of the United States to the other, he or she now likely does it five miles in the air, high above the countryâhigh above Nebraska. All the small towns flash by in an instantâon a cloudy day, it's as if they are not even down there.

And the country itselfâ¦the country itself at times seems to have gone away. At least a country in which neighbors would join together for five straight years, every

day and every night, just so they could provide kindness and companionship to people they had never met.

In a lot of ways, it is a country that many of us seem always to be searching for.

I wasn't at all certain what I would find when I got to North Platte.

But the people from the Canteenâthe people who came there on their own time to run it, the people who hurriedly ran inside to savor it, on their way to warâwill soon all be gone.

I wanted to get to North Platte before it was too late.