One and Wonder (22 page)

Authors: Evan Filipek

Now we knew what had hit Katherine Flent, and why Amy was empty and starved when we found her. Joe Flent had been killed by . . . one of the . . . well, by something that erupted at him as he bent over the trapped Clement. Clement himself had been struck on the side of the face by such a thing—and whose was that?

Why, that primate's. The primate he walked into submission, and touched, and frightened.

It bit him in panic terror. Joe Flent was killed in a moment of panic terror too—not this, but Clement's, who saw the rock-slide coming. Katherine Flent died in a moment of terror—not hers, but Amy's, as Amy crouched cornered in the shack and watched Katherine coming with a knife. And the one which had appeared on earth, in the psych lab, why, that needed the same thing to be born in—when the boys forced Glenda Spooner across a mental barrier she could not cross and live.

We had everything now but the mechanics of the thing, and that we got from Amy, the bravest woman yet. By the time we were through with her, every man in the place admired her g—uh, dammit not that. Admired her fortitude. She was probed and goaded and prodded and checked, and

finally went through a whole series of advanced exploratories. By the time the exploratories began, about six weeks had gone by, that is, six weeks from Katherine Flent's death, and Amy was almost back to normal; she'd tapered off on the calories, her abdomen had filled out to almost normal, her temperature had steadied and by and large she was okay. What I'm trying to put over is that she had some intestines for us to investigate—

she'd grown a new set.

That's right. She'd thrown her old ones at Katherine Flent. There wasn't anything wrong with the new ones, either. At the time of her first examination everything was operating but the kidneys; their function was being handled by a very simple, very efficient sort of filter attached to the ventral wall of the peritoneum. We found a similar organ in autopsying poor Glenda Spooner. Next to it were the adrenals, apparently transferred there from their place astride the original kidneys. And sure enough, we found Amy's adrenals placed that way, and not on the new kidneys. In a fascinating three-day sequence we saw those new kidneys completed and begin to operate, while the surrogate organ which had been doing their work atrophied and went quiet. It stayed there, though, ready.

The climax of the examination came when we induced panic terror in her, with a vivid abreaction of the events in the recording shack the day Katherine died. Bless that Amy, when we suggested it she grinned and said, “Sure!”

But this time it was done under laboratory conditions, with a high-speed camera to watch the proceedings. Oh God, did they proceed!

The film showed Amy's plain pleasant sleeping face with its stainless halo of psych-field hood, which was hauling her subjective self back to that awful moment in the records shack. You could tell the moment she arrived there by the anxiety, the tension, the surprise and shock that showed on her face. “Glenda!” she screamed, “Get Joe!”—and then . . .

It looked at first as if she was making a face, sticking out her tongue. She was making a face all right, the mask of purest, terminal fear, but that wasn't a tongue. It came out and out, unbelievably fast even on the slow-motion frames on the high-speed camera. At its greatest, the diameter was no more than two inches, the length . . .about eight feet. It arrowed out of her mouth, and even in mid-air it contracted into the roughly spherical shape we had seen before. It stuck the net which the doctors had spread for it and dropped into a plastic container, where it hopped and hopped, sweated, drooled, bled and died. They tried to keep it alive but it wasn't meant to live more than a few minutes.

On dissection they found it contained all Amy's new equipment, in sorry shape. All abdominal organs can be compressed to less than two inches in diameter, but not if they're expected to work again. These weren't.

The thing was covered with a layer of muscle tissue, and dotted with

two kinds of ganglia, one sensory and one motor. It would keep hopping as long as there was enough of it left to hop, which was what the motor system did. It was geotropic, and it would alter its muscular spasms to move it toward anything around it that lived and had warm blood, and that's what the primitive sensory system was for.

And at last we could discard the fifty or sixty theories that had been formed and decide on one: That the primates of Mullygantz II had the ability, like a terran sea-cucumber, of ejecting their internal organs when frightened, and of growing a new set; that in a primitive creature this was a survival characteristic, and the more elaborate the ejected matter the better the chances of the animal's survival. Probably starting with something as simple as a lizard's discarding a tail-segment which just lies there and squirms to distract a pursuer, this one had evolved from ‘distract’ to ‘attract’ and finally to ‘attack.’ True, it took a fantastic amount of forage for the animal to supply itself with a new set of innards, but for vegetarian primates on fertile Mullygantz II, this was no problem.

The only problem that remained was to find out exactly how terrans had become infected, and the records cleared that up. Clement got it from a primates bite. Amy and Glenda got it from Clement. The Flents may well never have had it. Did that mean that Clement had bitten those girls? Amy said no, and experiments proved that the activating factor passed readily from any mucous tissue to any other. A bite would do it, but so would a kiss. Which didn't explain our one crew-member who “contracted” the condition. Nor did it explain what kind of a survival characteristic it is that can get transmitted around like a virus infection, even between species.

Within that same six weeks of quarantine, we even got an answer to that. By a stretch of the imagination, you might call the thing a virus. At least, it was a filterable organism which, like the tobacco mosaic or the slime mold, had an organizing factor. You might call it a life form, or a complex biochemical action, basically un-alive. You could call it symbiote. Symbiotes often go out of their way to see to it that the hosts survive.

After entering a body, these creatures multiplied until they could organize, and then went to work on the host. Connective tissue and muscle fiber was where they did most of their work. They separated muscle fibers all over the peritoneal walls and diaphragm, giving a layer to the entrails and the rest to the exterior. They duplicated organic functions with their efficient, primitive little surrogate organs and glands. They hooked the ilium to the stomach wall and to the rectum, and in a dozen places to their new organic structures. Then they apparently stood by.

When an emergency came every muscle in the abdomen and throat cooperated in a single, synchronized spasm, and the entrails, sheathed in muscle fiber and dotted with nerve ganglia, compressed into a long tube

and was forced out like a bullet. Instantly the revised and edited abdomen got to work, perforating the new stomach outlet, sealing the old, and starting the complex of simple surrogate to work. And as long as enough new building material was received fast enough, an enormously accelerated rebuilding job started, blue-printed God knows how from God knows what kind of a cellular memory, until in less than two months the original abdominal contents, plus revision, were duplicated, and all was ready for the next emergency.

Then we found that in spite of its incredible and complex hold on its own life and those of its hosts, it had no defense at all against one of humanity's oldest therapeutic tools, the RF fever cabinet. A high frequency induced fever of 108 sustained for seven minutes killed it off as if it had never existed, and we found that the “revised” gut was in every way as good as the original, if not better (because damaged organs were replaced with healthy ones if there was enough of them left to show original structure)—and that by keeping a culture of the Mullygantz ‘virus’ we had the ultimate, drastic treatment for forty-odd types of abdominal cancer—including two types for which we'd had no answer at all!

So it was we lost the planet, and gained it back with a bonus. We could cause this thing and cure it and diagnose it and use it, and the new world was open again. And that part of the story, as you probably know, came out all over the newsfax and ‘casters, which is why I'm getting a big hello from taxi drivers and doormen . . . .

“But the ‘fax said you wouldn't be leaving the base until tomorrow noon!” Sue said after I had spouted all this to her and at long last got it all off my chest in one great big piece.

“Sure. They got that straight from me. I heard rumors of a parade and speeches and God knows what else, and I wanted to get home to my walkin’ talkin’ wettin’ doll that blows bubbles.”

“You're silly.”

“You’re silly.”

“C’mere.

The doorbell hummed.

“I'll get it,” I said, “and throw ‘em out. It's probably a reporter.”

But Sue was already on her feet. “Let me, let me. You just stay there and finish your drink.” And before I could stop her she flung into the house and up the long corridor to the foyer.

I chuckled, drank my ale and got up to see who was horning in. I had my shoes off so I guess I was pretty quiet. Though I didn't need to be. Purcell was roaring away in his best old salt fashion, “Let's have us another quickie, Susie, before the Space Scout gets through with his red carpet treatment tomorrow—miss me, honey?” . . . while Sue was imploringly trying to cover his mouth with her hands.

Maybe I ran; I don't know. Anyway, I was there, right behind her. I didn't say anything. Purcell looked at me and went white. “Skipper . . .”

And

in

the hall mirror behind Purcell, my wife met my eyes. What she saw in my face I cannot say, but in hers I saw panic and terror.

In the small space between Purcell and Sue, something appeared. It knocked Purcell into the mirror, and he slid down in a welter of blood and stinks and broken glass. The recoil slammed Sue into my arms. I put her by so I could watch the tattered, bleeding thing on the floor hop and hop until it settled down on the nearest warm living thing it could sense, which was Purcell's face.

I let Sue watch it and crossed to the phone and called the commandant. “Gargan,” I said, watching. “Listen, Joe. I found out that Purcell lied about where he went in that first liberty. Also why he lied.” For a few seconds I couldn't seem to get my breath. “Send the meat wagon and an ambulance, and tell Harry to get ready for another hollow-belly. . . . Yes, I said, one dead. . . . Purcell, dammit. Do I have to draw you a cartoon?” I roared, and hung up.

I said to Sue, who was holding on to her flat midriff, “That Purcell, I guess it did him good to get away with things under my nose. First that helpless catatonic Glenda on the way home, then you. I hope you had a real good time, honey.”

It smelled bad in there so I left. I left and walked all the way back to the Base. It took about ten hours. When I got there I went to the Medical wing for my own fever-box-cure and to do some thinking about girls with guts, one way or another. And I began to wait. They'd be opening up Mully-gantz II again, and I thought I might look for a girl who'd have the . . . fortitude to go back with me. A girl like Amy. Or maybe Amy.

Sturgeon’s finesse of description came through again. I did have trouble tracking all the characters, but got by. I see this as a superb integration of a spectacular idea—the expelled guts—with human conflict to evoke those guts, and a nice science mystery that gradually gets fathomed. I had not remembered the final twist at all. In that situation I would go with Amy, who strikes me as an ideal woman. She had physical and emotional guts galore. This remains a top story. I understand that Miller, author of “Vengeance for Nikolai, “ and Sturgeon, author of “The Girl Had Guts,” each thought the other's story was superlative. Both were right.

—Piers

THE LITTLE LOST ROBOT

Isaac Asimov

March 1947

This was the first Asimov robot story I read, and I can't claim it's the best, just the one that introduced me to a subsection of science fiction that I still like very well. I have had intelligent self-willed humanoid robots in my own fiction, notably the Adept series and the final volume of the ChroMagic Series. My robots do not follow the Asimov Laws of Robotics, but I was surely influenced by them. I remember the problem of identifying a robot that looks and acts exactly like others of its type, but has slightly different software, making it potentially dangerous. How do you spot such a robot, when it doesn't want to be spotted? There's the riddle, with a nice solution. Asimov was good at intellectual riddles and solutions. My contact with him was only one exchange of letters, and in the fanzines, but we were similar in our need to be constantly writing, regardless where we are. Other writers seem to like to get away from writing; we two never wanted to get away. As a result, Asimov wrote more than 300 books, mostly nonfiction. My total is about half that, but I actually have written more fiction than he did.

—Piers

When I did see Susan Calvin again, it was at the door of her office. Files were being moved out.

She said, “How are your articles coming along, young man?”

“Fine,” I said. I had put them into shape according to my own lights, dramatized the bare bones of her recital, added the conversation and little touches, “Would you look over them and see if I haven't been libelous or too unreasonably inaccurate anywhere?”

“I suppose so. Shall we retire to the Executives’ Lounge? We can have coffee.”

She seemed in good humor, so I chanced it as we walked down the corridor, “I was wondering, Dr. Calvin—”

“Yes?”

“If you would tell me more concerning the history of robotics.”

“Surely you have what you want, young man.”

“In a way. But these incidents I have written up don't apply much to the modern world. I mean, there was only one mind-reading robot ever developed, and Space-Stations are already outmoded and in disuse, and robot mining is taken for granted. What about interstellar travel? It's only been about twenty years since the hyperatomic motor was invented and it's well known that it was a robotic invention. What is the truth about it?”

“Interstellar travel?” She was thoughtful. We were in the lounge, and I ordered a full dinner. She just had coffee.

“It wasn't a simple robotic invention, you know; not just like that. But, of course, until we developed the Brain, we didn't get very far. But we tried; we really tried. My first connection (directly, that is) with interstellar research was in 2029, when a robot was lost—”

Measures on Hyper Base had been taken in a sort of rattling fury—the muscular equivalent of an hysterical shriek.

To itemize them in order of both chronology and desperation, they were:

1. All work on the Hyperatomic Drive through all the space volume occupied by the Stations of the Twenty-Seventh Asteroidal Grouping came to a halt.

2. That entire volume of space was nipped out of the System, practically speaking. No one entered without permission. No one left under any conditions.

3. By special government patrol ship, Drs. Susan Calvin and Peter Bogert, respectively Head Psychologist and Mathematical Director of United States Robot & Mechanical Men Corporation, were brought to Hyper Base.

Susan Calvin had never left the surface of Earth before, and had no perceptible desire to leave it this time. In an age of Atomic Power and a clearly coming Hyper-atomic Drive, she remained quietly provincial. So she was dissatisfied with her trip and unconvinced of the emergency, and every line of her plain, middle-aged face showed it clearly enough during her first dinner at Hyper Base.

Nor did Dr. Bogert’s sleek paleness abandon a certain hangdog attitude. Nor did Major-general Kallner, who headed the project, even once forget to maintain a hunted expression.

In short, it was a grisly episode, that meal, and the little session of three that followed began in a gray, unhappy manner.

Kallner, with his baldness glistening, and his dress uniform oddly un-suited to the general mood, began with uneasy directness.

“This is a queer story to tell, sir, and madam. I want to thank you for coming on short notice and without a reason being given. We'll try to correct that now. We've lost a robot. Work has stopped and

must

stop until such time as we locate it. So far we have failed, and we feel we need expert help.”

Perhaps the general felt his predicament anticlimactic. He continued with a note of desperation, “I needn't tell you the importance of our work here. More than eighty percent of last year's appropriations for scientific research have gone to us—”

“Why, we know that,” said Bogert, agreeably. “U. S. Robots is receiving a generous rental fee for use of our robots.”

Susan Calvin injected a blunt, vinegary note, “What makes a single robot so important to the project, and why hasn't it been located?”

The general turned his red face toward her and wet his lips quickly. “Why, in a manner of speaking we

have

located it.” Then, with near anguish, “Here, suppose I explain. As soon as the robot failed to report, a state

of emergency was declared, and all movement off Hyper Base stopped. A cargo vessel had landed the previous day and had delivered us two robots for our laboratories. It had sixty-two robots of the . . . uh . . . same type for shipment elsewhere. We are certain as to that figure. There is no question about it whatever.”

“Yes? And the connection?”

“When our missing robot failed of location anywhere—I assure you we would have found a missing blade of grass if it had been there to find—we brain-stormed ourselves into counting the robots left of the cargo ship. They have sixty-three now.”

“So that the sixty-third, I take it, is the missing prodigal?” Dr. Calvin's eyes darkened.

“Yes, but we have no way of telling which is the sixty-third.”

There was a dead silence while the electric clock chimed eleven times, and then the robopsychologist said, “Very peculiar,” and the corners of her lips moved downward.

“Peter,” she turned to her colleague with a trace of savagery, “what's wrong here? What kind of robots are they using at Hyper Base?”

Dr. Bogert hesitated and smiled feebly, “It's been rather a matter of delicacy till now, Susan.”

She spoke rapidly, “Yes,

till

now. If there are sixty-three same-type robots, one of which is wanted and the identity of which cannot be determined, why won't any of them do? What's the idea of all this? Why have we been sent for?”

Bogert said in resigned fashion, “If you'll give me a chance, Susan—Hyper Base happens to be using several robots whose brains are not impressioned with the entire First Law of Robotics.”

“Aren't

impressioned?” Calvin slumped back in her chair. “I see. How many were made?”

“A few. It was on government order and there was no way of violating the secrecy. No one was to know except the top men directly concerned. You weren't included, Susan. It was nothing I had anything to do with.”

The general interrupted with a measure of authority. “I would like to explain that bit. I hadn't been aware that Dr. Calvin was unacquainted with the situation. I needn't tell you, Dr. Calvin, that there always has been strong opposition to robots on the Planet. The only defense the government

has had against the Fundamentalist radicals in this matter was the fact that robots are always built with an unbreakable First Law—which makes it impossible for them to harm human beings under any circumstance.

“But we

had

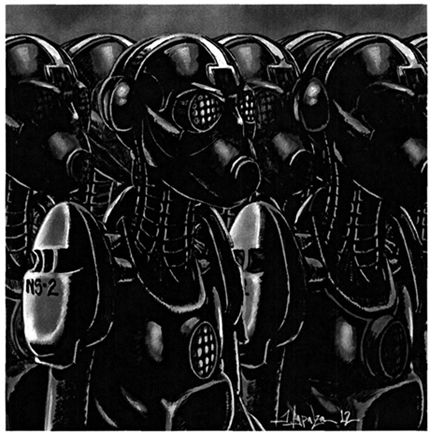

to have robots of a different nature. So just a few of the NS-2 model, the Nestors, that is, were prepared with a modified First Law. To keep it quiet, all NS-2’s are manufactured without serial numbers; modified members are delivered here along with a group of normal robots; and, of course, all our kind are under the strictest impressionment never to tell of their modification to unauthorized personnel.” He wore an embarrassed smile, “This has all worked out against us now.”

Calvin said grimly, “Have you asked each one who it is, anyhow? Certainly, you are authorized?”

The general nodded, “All sixty-three deny having worked here—and one is lying.”

“Does the one you want show traces of wear? The others, I take it, are factory-fresh.”

“The one in question only arrived last month. It, and the two that have just arrived, were to be the last we needed. There's no perceptible wear.” He shook his head slowly and his eyes were haunted again, “Dr. Calvin, we don't dare let that ship leave. If the existence of non-First Law robots becomes general knowledge—” There seemed no way of avoiding understatement in the conclusion.

“Destroy all sixty-three,” said the robopsychologist coldly and flatly, “and make an end of it.”

Bogert drew back a corner of his mouth. “You mean destroy thirty thousand dollars per robot. I'm afraid U. S. Robots wouldn't like that. We'd better make an effort first, Susan, before we destroy anything.”

“In that case,” she said, sharply, “I need facts. Exactly what advantage does Hyper Base derive from these modified robots? What factor made them desirable, general?”

Kallner ruffled his forehead and stroked it with an upward gesture of his hand. “We had trouble with our previous robots. Our men work with hard radiations a good deal, you see. It's dangerous, of course, but reasonable precautions are taken. There have been only two accidents since we began and neither was fatal. However, it was impossible to explain that to an ordinary robot. The First Law states—I'll quote it—‘

No robot may harm

a human being, or through inaction

,

allow a human being to come to harm.

’

“That's primary, Dr. Calvin. When it was necessary for one of our men to expose himself for a short period to a moderate gamma field, one that would have no physiological effects, the nearest robot would dash in to drag him out. If the field were exceedingly weak, it would succeed, and work could not continue till all robots were cleared out. If the field were a trifle stronger, the robot would never reach the technician concerned, since its positronic brain would collapse under gamma radiations—and then we would be out one expensive and hard-to-replace robot.

“We tried arguing with them. Their point was that a human being in a gamma field was endangering his life and that it didn't matter that he could remain there half an hour safely. Supposing, they would say, he forgot and remained an hour. They couldn't take chances. We pointed out that they were risking their lives on a wild off-chance. But self-preservation is only the Third Law of Robotics—and the First Law of human safety came first. We gave them orders; we ordered them strictly and harshly to remain out of gamma fields at whatever cost. But obedience is only the Second Law of Robotics—and the First Law of human safety came first. Dr. Calvin, we either had to do without robots, or do something about the First Law—and we made our choice.”

“I can't believe,” said Dr. Calvin, “that it was found possible to remove the First Law.”

“It wasn't removed, it was modified,” explained Kallner. “Positronic brains were constructed that contained the positive aspect only of the Law, which in them reads:

No robot may harm a human being

.’ That is all. They have no compulsion to prevent one coming to harm through an extraneous agency such as gamma rays. I state the matter correctly, Dr. Bogert?”

“Quite,” assented the mathematician.

“And that is the only difference of your robots from the ordinary NS-2 model? The

only

difference? Peter?”

“The

only

difference, Susan.”

She rose and spoke with finality, “I intend sleeping now, and in about eight hours, I want to speak to whomever saw the robot last. And from now on, General Kallner, if I'm to take any responsibility at all for events, I want full and unquestioned control of this investigation.”

Susan Calvin, except for two hours of resentful lassitude, experienced

nothing approaching sleep. She signaled at Bogert's door at the local time of 0700 and found him also awake. He had apparently taken the trouble of transporting a dressing gown to Hyper Base with him, for he was sitting in it. He put his nail scissors down when Calvin entered.

He said softly, “I've been expecting you more or less. I suppose you feel sick about all this.”

“I do.”

“Well—I'm sorry. There was no way of preventing it. When the call came out from Hyper Base for us, I knew that something must have gone wrong with the modified Nestors. But what was there to do? I couldn't break the matter to you on the trip here as I would have liked to, because I had to be sure. The matter of the modification is top secret.”

The psychologist muttered, “I should have been told. U. S. Robots had no right to modify positronic brains this way without the approval of a psychologist.”